Malcolm Turnbull says he wants to do things with Indigenous people, not to them. 40 years ago, a visionary health program did just that. Thom Mitchell reports.

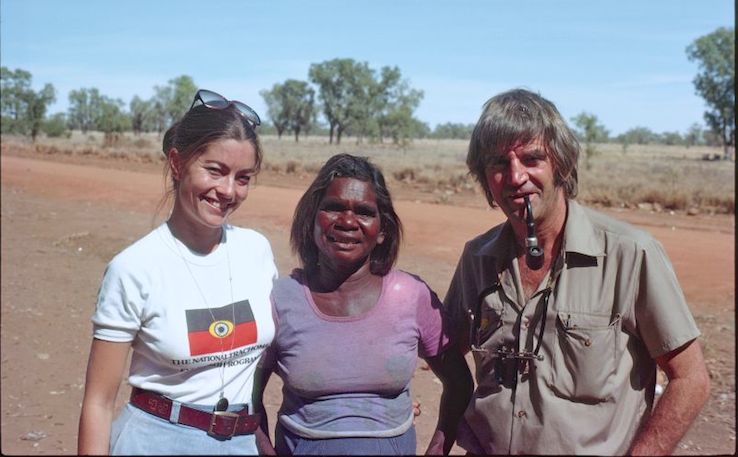

In the late 1970s, Fred Hollows punctured a hole in the ignorance and derision of mainstream Australia’s racism. Working mostly through the National Trachoma and Eye Health Program, he got out of the white station master’s house, down in red outback dirt, and listened to Aboriginal people.

The National Trachoma and Eye Health Program looked into more than 100,000 eyes, around 60 per cent of them Aboriginal. In the late seventies, 27,000 people were treated for trachoma, a contagious eye disease that had stopped sending white Australians blind decades before.

In many Aboriginal communities, though, up to 80 per cent of people were infected with the blinding bug. Hollows’ federally-funded program performed more than 1,000 operations, treating trachoma and other eye issues like cataracts.

Teams worked out of army tents, four wheel drives, and across the bush tracks which led to more than 465 remote communities. The pragmatism of this approach was central to its success, but so was a politics of self-determination, which was informed by the hundreds of Aboriginal people who worked with Hollows.

In the plush settings of Parliament last week, Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull promised to reset the relationship, and start to do things ‘with’ Aboriginal people, rather than ‘to’ them. He canvassed the results of the eighth Closing The Gap report-card – another fail grade – and he spoke one line in Ngunawal language.

He might have done better to be on the Fred Hollows Foundation bus heading to Bourke, the outback New South Wales town where the famous professor of ophthalmology is buried. There, he could have spoken to Gordon Briscoe, a driving force behind the trachoma program, about how to really do things ‘with’ Aboriginal people.

“We began educating [Fred Hollows] about not just health, but what people were thinking in their minds about getting rights, getting civil rights, getting involved in fighting against governments that were oppressing them,” Briscoe recalls.

In the tumult of the late sixties and into the seventies – through the campaign against the Vietnam war, and Apartheid South Africa – Aboriginal people across the the continent, and especially in Sydney, were waging a fight of their own.

They were drawing attention to a disgrace in Australia’s own backyard, straining to be heard above pervasive institutional racism. On Thursday last week, many of the people involved in that fight, and the national trachoma program as part of it, gathered around “the growly old fella’s” grave.

They remembered a fiercely practical man, who got in and did things ‘with’ Aboriginal people. A larrikin who would smoke in his ward, who dished out nicknames like ‘the degenerate aristocrat’, ‘the impregnator’, ‘coughin’ Jeff’, and ‘bundle of rags’.

Gabbi Hollows – or ‘bundle of rags’, as Fred called her – poured whiskey over the former Australian of the Year’s massive headstone.

It was a top up, it seems. The current Chair of the Redfern Aboriginal Medical Service, Sol Bellear tells New Matilda Fred Hollows was buried with a bottle. As a young man involved in the struggle for Aboriginal rights, Bellear travelled with Hollows from Sydney to Geraldton, in Western Australia.

“It was absolutely shocking,” he said. “You’d see people living in old cars, people living in tanks, people living in the dirt and all that sort of stuff, and then twenty yards up the road you’d see the mission manager’s house.”

“[It’d be] surrounded by green grass, with water going all the time, and he’d have a lush garden and you know a great big house with air conditioning and all that. Yet you could see the abject poverty that Aboriginal people had to live with – those conditions, no running water – and Fred knew that was what helped Trachoma spread.”

Hollows and the more than 1,000 people who supported him in the program also worked to improve this ‘health hardware’. They counted factors like housing and sanitation as the root cause of poor eye health in Aboriginal communities.

The service was holistic, with eye doctors working alongside ear throat and nose specialists, trailed by GPs, doing consistent follow-up work, and leaving health reports with local communities to give them information that would help them ‘close the gap’.

Aboriginal medical services would often spring up after the program went through, with doctors working to the needs identified by community committees so that Aboriginal people had ownership of the service.

There was a broader politics at play. Fred Hollows and his friends literally carried a chain and tackle to knock down ‘private property’ signs. Hollows pinched medical supplies from the University of New South Wales and the Royal College of Opthalmology, and used them to help those rendered needy by dispossession and discrimination.

The National Trachoma and Eye Health Program engaged around 700 people as Aboriginal Liaison Officers and Aboriginal Health Workers. Trevor Buzzacott was one of them. He speaks “three or four” Aboriginal languages, and visited bush communities throughout 1977.

As an Aboriginal Liaison Officer, his work involved learning protocol, language, and different communities’ concerns to pave the way for approaching doctors.

“I’ve not in my life seen the extent of engagement, whereby we had to speak through not only four different states, but so many different Aboriginal language groups,” Buzzacott said.

“We had to travel in so many of the remotest of areas. Communications were a problem, and we had to be self-sufficient. We had to make sure we were on the right pathways, and they knew we were coming.

“And we also had to make sure that when we went into any of these Aboriginal areas, we had to seek their permission and their cooperation in doing so. You can’t just go in.”

With us, not to us

On Wednesday, as Turnbull delivered his one line in Ngunawal language, Buzzacott was on the bus to Bourke. At the same time, the Prime Minister was sugar-coating what he called “mixed results” in his Closing the Gap report card. Perhaps misleadingly, he clung to the fact that two of the seven indicators of Aboriginal disadvantage were ‘on track’.

In his address, Turnbull recounted advise he’d been given by Aboriginal Educator Dr Chris Sarra, on how to address Indigenous disadvantage. “This is what he said,” Turnbull told Parliament:

“’Firstly, acknowledge, embrace and celebrate the humanity of Indigenous Australians. Secondly, bring us policy approaches that nurture hope and optimism rather than entrench despair. And, lastly, do things with us, not to us.’”

The Prime Minister promised he would.

As Brian Doolan, the Chief Executive Officer of the Fred Hollows Foundation points out, “Malcolm Turnbull’s not the first person. That’s been said time and time again”.

“To say that we need to engage with Indigenous communities, that is not news,” Doolan says.

“Where is the real transfer of power and resources into the hands of Aboriginal people to take control of their own destinies? That’s what Indigenous people are saying to Turnbull. ‘We’ve yet to see you do one thing – we’ve yet to see you actually do anything in relation to Indigenous Australians’. That was the first significant speech he’s made, and all he said is we need to learn how to talk to Aboriginal people.

“Well, whoopty doo. No great breakthrough there, unfortunately.”

Turnbull hailed “mixed results,” but as Amy McQuire wrote last week, the reality is that the gap is not closing. Governments are consistently failing their own test.

Last week also brought the anniversary of Kevin Rudd’s apology to the stolen generation – meanwhile, Aboriginal children are being taken at higher rates than at the time of the apology.

It’s a similar story with Indigenous eye health: you’d have to be wilfully blind not to see that ‘the gap’ is more like a gulf. Blindness rates in Indigenous adults are six times the mainstream rate, according to a 2015 report from the Melbourne University School of Population and Global Health Indigenous Eye Health team.

As it was during the late seventies, almost all of this vision loss – at 94 per cent – is preventable. Blinding cataracts are twelve times more common in Indigenous Australia, yet surgery seven times less likely. And waiting times 56 per cent longer.

The disparity is so stark, the report argues, that 11 per cent of the health gap is due to vision loss. That puts it “behind cardiovascular disease and diabetes, equal with trauma, but ahead of alcoholism and stroke”.

Trachoma has nearly been wiped out in Australia, but the modern scourge of diabetes is closely linked to issues with Indigenous eye health. “If you have diabetes and it’s uncontrolled, and it’s there for quite a while, you will go blind,” Joanna Barton tells me.

Barton is the Nurse Manager of the Outback Eye Service, which runs out of Bourke Hospital. An ongoing legacy of Hollows, the service is supported by Prince of Wales hospital, and is surviving on funding from the foundation which carries his name. The Federal Government grants Barton’s relied on are not enough.

“My greatest struggle is funding,” she tells New Matilda. “It frustrates me totally; I hear on the news millions of dollars, millions of dollars have been spent. I haven’t seen any of it. Whether I’m a poor manager or whatever, I see none of Closing the Gap.”

“There’s absolutely no-one out there saying ‘well this is the job you do, how can we help you’ from the government. It’s always you having to knock on the door and say ‘look we’re running out of money’.”

The Outback Eye Service also operates one day a week in Dubbo, where Barton said they’re facing “a tsunami of people”. Neither the state government, whose responsibility it ultimately is, nor the Commonwealth, is rushing to properly fund the Dubbo service.

Barton’s run the service out of Bourke for 16 years, and there hasn’t been one in which she hasn’t had to reapply for funds. And then there’s the impenetrable bureaucracy – the “layers and layers and layers of crap” – that could see Barton spending 10 hours arranging to transport a patient.

For Aboriginal organisations, the struggle is even greater.

According to Brian Doolan, it’s not unusual for an Aboriginal-run organisation to have to interact with eighty or ninety different funding bodies, “all of whom have different reporting requirements, different cycles of reporting timelines”.

“It’s a constant cycle of bureaucracy, under which people just collapse,” says Doolan, who’s spent much of his life working in Aboriginal organisations. “At the end of the day you go into the communities and what you find is basically whitefellas in Toyotas coming in and out, going through processes that they refer to as consultation, and people are being consulted to death without outcomes,” he said.

“…and that was the difference that the trachoma program, that people like Gordon Briscoe and Trevor Buzzacott, they didn’t just go in and talk to people. They went in and they’d say ‘no survey without service’. You know, ‘we’re not coming in just to ask your opinion or just to have a look in your eyes: if there’s a problem we will treat it on the spot or we will follow up’.”

Looking ahead

The National Trachoma and Eye Health Program was perhaps the first major break from missionary approaches to supporting Aboriginal communities, and a breakthrough in the delivery of tangible health services.

As such, it blazed a trail for how Indigenous people could take ownership of essential services in remote areas, and the trust that needed to be built for frontline services to be effectively delivered. Sol Bellear recalls how “at one stage, nobody wanted to wear glasses, didn’t want a thing to do with them.

“Then somebody put them on, and they could read or they could do something a little better, they could see properly, and someone said ‘oh you look good in glasses’ and they’d be talking away in language,” he said.

“Then glasses became a sort of a fashion statement, because once Aboriginal people, and particularly the elders, once they got wearing glasses people would come up even the ones that didn’t need glasses, they’d demand we give them a pair of glasses.

“OPSM then had to put ordinary glass into the frames. And Fred – he had a real raspy voice, Fred – he’d hand them out to people. ‘Oh give ‘em a pair of glasses,’ he’d say. ‘Give ‘em a pair of glasses’. It became a big fashion statement.”

Revisiting the work of the program last week was Aboriginal doctor Kris Rallah-Baker. He’s on track to become the first Aboriginal Ophthalmologist and like Doolan he’s adamant that “Indigenous people have to be involved, otherwise it’s like the old mission days”.

“[If] you just dictate to Aboriginal people that will never work. It’s human nature that if someone tells you have to do something, and you don’t want to do that, you’re not being respected, well I mean you’re not going to get outcomes,” he says.

Rallah-Baker believes issues in Aboriginal health are hampered by the fact Australia hasn’t had a national conversation about the “fundamental issues,” like sovereignty and treaty. “We need a genuine and frank conversation about not only contemporary issues but everything that brought us here,” he says.

“I think as a country, unfortunately, we still aren’t absolutely honest with how we’ve ended up where we are.”

Brian Doolan maintains that the only way to move away from the sharp divide between Indigenous and non-Indigenous health is to develop an a-political, long-term commitment to properly resourcing Indigenous people to take ownership of services.

“We have never really put the resources in any comprehensive way into the hands of Indigenous people, to control their own lives and to take control of those myriad forces that come in and out of communities.

“That’s what Gordon [Briscoe] was saying the other day. He was saying that Fred Hollows didn’t come along and sort of go out himself and do all this, he got caught up in a movement of Indigenous people who were saying ‘we want to control out own lives, we want to control our own destinies’.

“Fred became the recognised figurehead of it, but it was actually that he was part of a movement of Aboriginal people who were saying ‘we want to control our own lives’.”

Thom Mitchell travelled to Bourke and Dubbo as a guest of the Fred Hollows Foundation.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.