OPINION: The world’s most famous doll is with us forever, but not in the ways you might imagine, writes Dr Liz Conor.

How are there Humans? my five year old once piped from the backseat. The poor child. Evolutionary Biology was lurking without pretext in my working memory that singular morning.

I dragged her through a tour de force detour around sex ed, careening instead through the fossil record, starting with the last common ancestor then single cell archaea, onwards to amoeba, and (skipping the odd 300 million years here and there) to the lobe-finned fishies coming ashore on their finny little legs, then to our low-browed hominin ape-like ancestors coming down from the trees to dodge the leopards while foraging on the savannah… I quite surpassed myself.

Her little sister ungobbed her thumb, ‘What about the Barbies’.

‘Mattel makes them’, was all I could manage.

As of yesterday, we can safely add something about the ‘evolution of Barbie’. For Mattel has just launched a make-over Barbie and she has finally achieved multi-cellular status. She has speciated from a poorly adumbrated physiognomic misfit who couldn’t stand in bare feet to a range of dolls that might reflect the diversity of little girls presently upright in platform sandals.

Huzzah! Identity politics has leached into polymer DNA sequencing. Either that or Barbie has literally had plastic surgery/implants. Little girls the world over can now imagine themselves in 7 skin tones (actually this bit is good) of adult with three new body types.

By Mattel’s theory of natural selection, women can be molten to three categories: Tall thin, petite and curvy. Since she has taken her place in the fossil record (more on that later) we might identify her by her species morphology as Barbia Longileggia, Barbia Petitia or Barbia Curvacea. Cornered by the corner stone of modern science, Barbie is now better adapted to the biophysical environment inhabited by humans. Her pelvis have evolved to birth babies with greater ease and some of her kind appear to have blue hair.

An indifference to accessorise, clearly indoctrinated by Barbie being banned from my childhood home, has me querying whether her newfound need to mix and match in three new sizes might not rather bump up the market value of her clothing range. As actually alive women know, changing sizes can be damnably expensive.

Mattel executives have dialed our kids’ ‘reptilian hot spots’ into three body ‘codes’ designed to elicit certain emotions like ‘accepted’ and ‘loyal’ in their malleable-minded customers, aka carpers and the Mummies who exhaustedly fork out.

I confess I too tried to leave Barbie out of my girls’ gender construction. I didn’t want this saccharine smiling Voodoo Doll of hegemonic femininity to appear as the archetype of the natural order.

Fat chance. She ruptured through my feminist superego in the form of deceptively wrapped birthday presents. Barbie brand hats, bags, pencils and trinkets inveigle themselves into our lives.

Whether we like it or not, little girls undergo a kind of Barbie experiment – without ethics approval – along the ‘P’ axis of girlie consumption – Princess, Pony and Pink.

It defines a girlie community of shared interests and enables a common language centered on her logo, emblazoning as it invariably does crèche bags, gumboots, lunchboxes, potties, pull-ups, you name it.

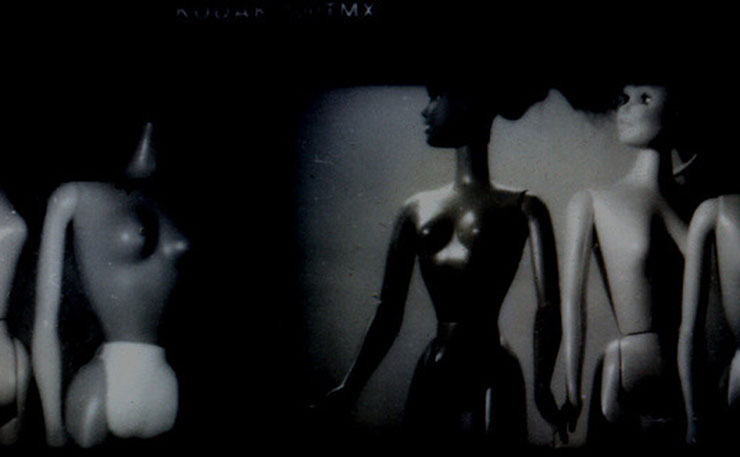

Yet I notice, not without malice, that even Barbie cannot withstand the ordeals of ‘interpretive play’ in the play rituals of little girls. Her tresses are shorn, she is hung by the neck, stripped and paraded through the local shopping mall and pelted with stones.

If they burn Barbie at the stake and bind her feet, she’ll have completed the circuit of special punishments meted out to women across the ages.

This gives me faith that there is precious and uncharted terrain in children’s grey matter that remains uninfluenced by toy corporations, as yet unknown to demographic database companies who track their every purchase and sell their consumer preferences to advertisers.

Barbie may well mutate. She may reconfigure the corporeal simulacra of modern intersecting femininity, or somethingorother. She might even empower overweight little girls to feel normalized about being overfed. But the real evolution in Barbie lies not in her appearance, but in her make up.

Yes, it is the substance of Barbie that really matters, what lies beneath the surface of all the Malibu frou frou and Presidential chic. She will actually enter the fossil record because of pulverized plastic compounds now leaching into every substrata from deep ocean beds to Artic ice tables.

HOUSE AD – NEW MATILDA IS A SMALL, INDEPENDENT MEDIA OUTLET. MOST OF OUR STAFF AND WRITERS ARE UNPAID. IF YOU WANT TO HELP SUPPORT INDEPENDENT MEDIA, YOU CAN DONATE A COUPLE OF DOLLARS TO OUR POZIBLE CAMPAIGN HERE OR SUBSCRIBE TO NEW MATILDA HERE.

Barbie was once more toxic than we knew. Vintage Barbies suffer a terrible fate – ‘doll disease’ – in which the plastic from which they are moulded disintegrates and oozes a plasticizer which mimics estrogen and can disrupt development in children’s reproductive systems.

Since banned in toy manufacture, Barbie has not fully evolved from polyvinyl chloride (vinyl or PVC), a thermoplastic polymer. Mattel has claimed she is no longer softened by phlalates, but during production and disposal Barbie can emit the byproduct dioxin, a carcinogen.

Human evolution may be more linked to Barbie’s than merely the visual identification of little girls. Awash in a sea of plastic products she contributes to one of the markers of the new geological epoch, the Anthropocene, the epoch defined by human activities having a determining global impact on Earth’s geology and ecosystems.

We have now produced enough plastic since WWII to coat the earth in clingwrap. More than 300 million tonnes of plastic is manufactured every year, nearly the weight of the human population. Barbie’s weight in plastic, however Mattel might diversify it, is a significant contributor.

If body dysmorphia, albeit now variegated into three standardised shapes, wasn’t bad enough, the very plasticity of Barbie currently being applauded may pose a threat to the same generation of consumers she ‘targets’, as she smilingly ushers them into the environmental dystopia that is the Anthropocene.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.