One of the nation’s most renowned electronic retailers is in receivership, and hundreds of jobs are to go. Gilchrist Clendinnen sifts through the mess to explain how it happened, and who is responsible.

On the 28th of October 2015 Nick Abboud, the CEO of Dick Smith scheduled a conference call for investors. October had been a disastrously bad month. Revenue had been well down on projections and as a result Dick Smith’s forecasted profit expectations were being abandoned.

Abboud sounded stressed but determined.

“We are going to have to fight our way out of it,” he said, outlining his strategy for the next eight weeks leading into Christmas.

The plan was simple but direct; cut prices, increase advertising. There were going to be daily ads on TV and radio from now into Christmas outlining the heavily discounted deals that they were currently putting together.

The reduced pricing and increased advertising threatened profit margins but Abboud was adamant this was the right decision. “When things are tough you have to change gears,” he said.

The words bankruptcy or receivership weren’t mentioned once.

Abboud answered each question confidently and seemed to be able to tell a coherent story about his strategy. While Dick Smith’s share price had fallen from over $1.25 to 69 cents immediately following the announcement, over the next two days the share price rose 17 per cent to around 82 cents, giving the company a depressed though hardly catastrophic valuation of $193 million.

By and large, the market seemed to have bought Abboud’s plan.

Around a month later, on the 30th of November, the markets faith in Abboud was dealt a major blow. Dick Smith released an announcement that they were writing down their inventory by $60 million, a 20 per cent adjustment. November sales had gone badly, meaning stock levels were still too high and inventory was quickly becoming obsolete.

This time there was no conference call, just a one-page announcement via the ASX.

“We remain cautious on the outlook for the Christmas trading period… we will continue to drive sales, maintaining flexibility on gross margins to reduce inventory and improve our net debt position,” was the only quote from a much less rambunctious sounding Abboud.

Despite the disappointing November, Abboud seemed to be doubling down on his strategy outlined in the October conference call.

A few days later, on the 4th of December, Dick Smith kicked off a massive clearance sale, discounting large portions of stock by as much as 70 per cent. It seemed like an all or nothing strategy, an attempt to burn through the remaining excess inventory before Christmas in order to start 2016 with a clean slate.

As it turned out, Dick Smith barely made it to 2016. On the 4th of January, the first Monday of the new year, Dick Smith suspended trading pending a major announcement.

On Hot Copper, the online investment forum, the mood was pretty grim. While some hoped that the announcement could be about a new credit line, the overwhelming consensus was that this was bad news.

They didn’t have to wait long to find out: a few hours later came a brief announcement that its lenders were refusing to extend a credit line to Dick Smith; the company was going into receivership.

Knowing what we do now, it is easy to see Dick Smith’s decline as inevitable, though on the day of Dick Smith’s bankruptcy announcement the company was still valued at around $84 million on the ASX.

While it is tempting to paint anyone who still owned Dick Smith shares after a string of negative announcements as foolish or naïve, in reality few could have predicted the speed of Dick Smith’s deterioration.

Only a couple of months earlier, on the 28th of August, Dick Smith had released an annual report that had been almost triumphant in tone. The report had shown a 3.1 per cent growth in profit and had been littered with quotes about senior management’s pride in the business and its prospects.

Even better, according to the same annual report, Dick Smith still had $68 million of room left of a $135 million pooled credit facility, a seemingly comfortable amount of fat considering the most profitable time of year was approaching.

So how did things go so wrong so quickly? How does a retail company that released a positive annual report in August go into receivership on the first working Monday of 2016?

To understand this question we have to go back in time to the late 2012, when Dick Smith was sold by Woolworths.

Dick Smith had been a consistent underperformer for Woolworths for a number of years and in 2012 Woolworths got out, selling the business for $110 million to the private equity firm Anchorage Capital.

What was interesting about this purchase though was only $20 million was required up front. This enabled Anchorage to fund the remaining $90 million from Dick Smith’s own balance sheet, liquidating large amounts of inventory to cover the remaining payment to Woolworths.

In total, it has been estimated that once the inventory liquidations and the existing cash on Dick Smith’s balance sheet have been taken into account, Anchorage Capital only spent $10 million of its own money to purchase Dick Smith (the investment fund Forager funds gives an excellent explanation of this on their blog).

This seems to be a pretty good bargain, but it gets more impressive when one considers what happened next. On the 14th of November 2013 Anchorage Capital announced that Dick Smith was to be sold to the public via an IPO at a price of $520 million, meaning that Anchorage Capital was claiming that they had turned $10 million into $520 million in around 12 months.

To justify a valuation of this magnitude Anchorage went the hard sell. Prospective investors were informed that “the new management team, led by Nick Abboud has driven a rapid transformation of Dick Smith through the implementation of a comprehensive program of strategic, customer, operational and cultural initiatives.”

There was a lot of talk of innovate inventory management, fast online growth and Dick Smith’s Move Stores, a new format of shop designed to target “a younger and more affluent demographic”.

In line with the inflated rhetoric, there was a string of inflated numbers. While net profit had ranged from $15 million to $6 million over the last couple of years, the forecast was that this would rise to $40 million in 2014, with impressive projections for future years after that.

While some analysts expressed concern at the high valuation, the IPO was successful at Anchorage’s quoted price. Anchorage sold all but 20 per cent of their stake in the company, selling off the remainder of their shares in Dick Smith less than a year later at a similar price.

While massive growth projections had successfully allowed Anchorage Capital to sell their shares, they presented a significant challenge for Abboud and his management team. Dick Smith was operating in a highly competitive industry, and had been losing market share to both Harvey Norman and JB Hi Fi.

Abboud was meant to somehow turn this trend around over the next 12 months, all the while maintaining a reasonable profit margin.

In addition to dealing with these highly ambitious growth targets, Nick Abboud had another problem; a severely depleted inventory.

Anchorage’s strategy of funding the purchase of Dick Smith through Dick Smith’s own balance sheet meant that as of the start of the 2013/14 financial year, Dick Smith had only $168 million worth of inventory, with a target to sell $918 million worth of stock for the year.

To achieve sales of this volume without increasing inventory the average time between purchasing goods, shipping them to a store and selling them to a customer would have to be only just over 2 months, a difficult logistical challenge for any retail business (by way of comparison, Harvey Norman, a very experienced business and market leader in the field, had failed to get their inventory turnover below 3 months for the last three years).

While the prospectus talked about innovative supply chain and inventory management techniques that would help keep inventory levels down, Dick Smith’s management team obviously concluded that a sub 3 month inventory turnover was unobtainable, and over the next few years inventory levels rose sharply.

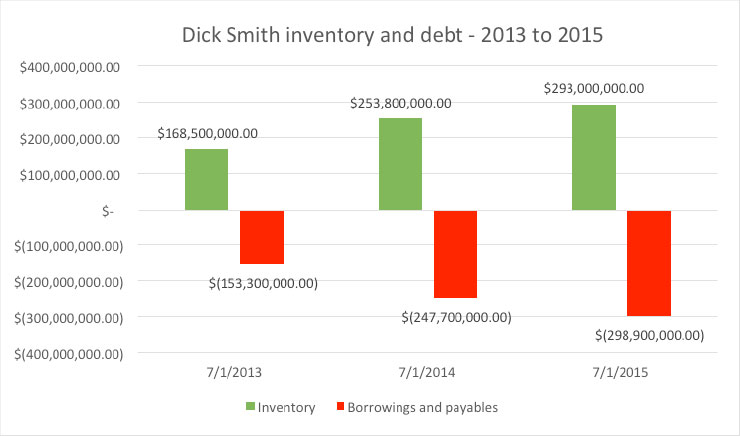

In order to pay for these inventory increases, the company was forced to increase debt and payables. The below graph charts Dick Smith’s inventory total and borrowings/payables over the last three years.

Increasing both debt and inventory rapidly for an electronic retail company is always going to be risky. The shelf life of electronic products are dangerously short, which means if sales lag behind projections you can be left with large amounts of out-of-date stock.

To make matters worse, the debt Dick Smith racked up was all short term, reducing the margin for error significantly. While we do not yet have an updated set of accounts for Dick Smith, recent reports suggest that Dick Smith’s combined payables and debt reached $290 million by the 4th of January.

This suggests that Abboud went all out on his Christmas sale strategy, spending large amounts on advertising while continuing to cut prices. For a CEO to continue such a high risk strategy in the face of repeated losses shows a considerable amount of single-mindedness.

Looking back on the series of events and decisions that lead to Dick Smith’s downfall, the $520 million valuation by Anchorage Capital seems like one of the main causes of what went wrong.

The unreasonably high valuation seemed like a yoke around management’s neck, influencing every decision over the last two years. It forced Abboud to try and grow too quickly, bringing large amounts of debt onto the balance sheet in the process.

When sales started to drop in late 2015, a possible reaction would have been to slow down the expansion plans and cut costs, but for a company that had made the sort of promises that Dick Smith did in 2013, this would have been admitting major defeat.

So instead, Abboud doubled down, slashing prices and raising advertising costs in a desperate bid to maintain momentum. By trying to convince the market that a $110 million company was worth $520 million, he ended up making it worth nothing.

Anchorage capital made a small fortune from the 12 months they spent reorganizing the company, and reasonable to suggest they helped sow the seeds for Dick Smith’s bankruptcy in the process.

A couple of days ago, I went into a Dick Smith store with my girlfriend. There was a pretty weird vibe – all the staff were cleaning in a way that somehow seemed both panicked and sullen.

We bought an SD card from a guy in his mid-twenties, I wanted to ask him what he thought about the news, but it felt inappropriate. I wonder what he’s going to do now, I thought, as he printed our receipt out.

It seemed almost obscene to think that he would probably be out of a job soon, all because a bunch of private equity investors he’d never even met got too greedy a couple of years ago.

As we headed for the exit I noticed that there were big signs at the entrance saying “knockout sale,” left over probably from Abboud’s all or nothing pre-Christmas clearances.

All things considered it seemed like an apt choice of words.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.