30 years ago, it would have been unthinkable to Australians that they would lock up men, women and children without charge, in conditions likened to a concentration camp. And yet, here we are. In this special feature, Julie Macken charts the course that made Australia an international pariah for its treatment of the world’s most vulnerable people – those seeking asylum.

He heard their muffled footsteps as they moved across the tiled entrance of his grandmother’s house. The stillness of mid-morning briefly disturbed as light and dust swirled through the front door in their wake.

His grandmother, Nadira, had just left for the market, “to get out and get back before the sun makes it too hard for an old woman”. She had laughed saying this, just as she had smiled and grinned about everything since his return to Lahore two weeks ago.

The scene from his homecoming could have been source footage for an airline commercial – not a dry eye to be seen. And why would there be? Her grandson who was lost had returned after two years on the run. Watching his slight figure as he emerged from behind the security doors of the airport she promised herself that she would keep him safe. She would feed him and find him a wife and he would remind her of her son, her beautiful dead son. “My husband has been taken and my only son, but Allah is great and my grandson returns to me in my old age,” she told him as she held his face in her tired, dry hands.

The assassins moved quickly, surefooted and focused as they homed in on their target.

Here in the top room he had two choices. He could make a run for it across the rooftops or try to take them by surprise and barge past them down the stairs.

But even as his plan formed it dispersed. They were militia, professionals in an army that tolerated nothing less than perfection. There would be no running away like a cat across the tiles for him. As he turned to face the entrance they appeared, moving quickly to either side of the door.

The younger one glanced around and shut the door before dropping the heavy bolt into place. The older man grabbed a chair and, putting it in the centre of the room, pointed his gun at Ali and told him to sit.

“Is this it?” asked Ali not moving. “Is this how it ends, with one Muslim brother killing another?”

“That’s your problem, friend,” answered his assailant. “You are not my brother and for you this is certainly how it ends. Please do not make it any harder than it needs be, we take no pleasure in your pain.” Moving across the room the intruder took Ali by the arm and gently escorted him to the chair, saying, “Your family knew the penalty for disloyalty, your grandfather paid, your father paid and now you must pay as well. But you do have a choice over pain and suffering – we give you that choice.”

Ali’s mind flashed back to a starlit night years before, leaning on the prow of an unlikely vessel as it slipped through the Arafura Sea en route from Indonesia to Australia. Finishing his last cigarette for the day he had been joined by Hassan, a man twice his age from Afghanistan’s Ghazni province. Like a shadow he had appeared next to Ali and, staring into the phosphorous spilling down their wake, he began to talk. In that twilight world of ocean and darkness, between leaving and arriving, Hassan told Ali about his family and his history.

As dawn broke and the coastline of Australia came into view, Hassan finished his story, saying: “Those spy stories lie, Ali. No-one withstands torture. The torturer comes to you and you have one choice – you can tell him everything before he burns your eyes out, or you can tell him everything after he puts them out. But you will tell him everything, you will give him everything, you will with hold nothing back. But know this too, Ali, it is a contagious business. No-one tortures another human being without becoming contaminated by their own horror.”

Sitting on the chair, Ali stared hard at the older assassin. The man was deft and minimal in his movements – an artisan at work. “Why the black turban of the Taliban?” asked Ali. “You are no students.” The older man stopped unpacking his bag and sat back on his haunches, inches from Ali’s face. Smiling kindly he answered: “No we are not Taliban. But if we are seen leaving this house all anyone will be able to tell the police is that we were Taliban. Everyone knows the Taliban are mad and kill for the sake of killing. It will suit us all to blame them.”

“Yes, it suits everyone, doesn’t it?” thought Ali. “If the Taliban had not existed, the world would have had to invent them.”

But the madness of this moment in the big world was no longer his concern. His concern was to avoid humiliating himself in these final moments and his obligation was to cry. The tears were not for him: they were not for his death, but for his beautiful grandmother who would return to a house of such sorrow.

She would bring the food back from the market, and as she bustled about the kitchen she would sing out for him to come and see what she would make for him. She would call his name loudly, then a little louder. She would not call any more. She would walk up the stairs slowly to his room, studying the locked wooden door. She would not try to push the door; she would simply fold to the floor, finally too hurt to stand again.

As the younger man bound his hands and feet, the old soldier squatted and took out a syringe. Taking the cap off, he shot some fluid into the air.

“I am comforted that you take such care to avoid putting air in my veins,” said Ali. “It would be too sad to die from misadventure.”

The older man looked at him and smiled, saying, “This won’t hurt a bit.”

As he carefully put the pick into Ali’s vein and depressed the plunger, Ali felt the warm euphoria surge up from his smooth brown feet to his hair.

What an irony, he thought – dying from the very drug his entire family had spent generations fighting.

His breath grew light and flighty, more a flutter than a pump. As death stole through his veins his mind slipped back to his friends in Sydney’s Balmain. The day, two weeks before when he had tried so hard not cry, so hard to smile and be brave. “If it is Allah’s will, we will meet again on this earth,” he told his friends.

Irene had looked at him through her own tears and said: “With respect Ali, Allah had nothing to do with your deportation – that man’s name is Philip, not Allah. Please don’t blame Allah for this obscenity.”

They had hugged forever. She had patted his back as though he were a little baby, wetting his T-shirt with her tears.

“It will be OK,” he assured them. “I will ring as soon as I get there. And believe me, my grandmother may be old but she is no fool – we will be fine in Lahore. No-one knows where I have been and no-one will know I have returned.”

He had lied to his friends from the Uniting Church. They had worked so hard for his freedom and been so generous with their courage and outrage. He had been caught up in their hope and Australia’s own propaganda. For a moment he had truly believed life would be different, that unlike the rest of the world, this little country would follow the rule of law, would rescue the last, the lost and the least.

He didn’t have the heart to tell his dear friends about the big world. About the world of 2 million refugees, of tribal borders that bore no resemblance to those tidy maps they kept presenting to the Refugee Review Tribunal – hoping this time it would find him a refugee worthy of Australia’s protection. For this brand new country the past was what happened last week. How could he tell them that in the big world, the past stretched back for millennia?

He knew he would be found and, when he was, he would be killed. But what could he say to his Australian friends? Australians would never understand and that’s why he had loved the country so well. “No-one has any idea how the world works here,” he had told his Pashtun migration lawyer. “They all think the world follows the rules of the lolly-pop man. They think because they say something is so, it is so.”

His Hazaran friends had wondered why he had bothered to seek the services of a Pashtun. His friend in Villawood detention centre had suggested it was like a Jew asking a Nazi for assistance. “True,” he had said. “But beggars cannot be choosers and I am nothing if not a beggar in this country.”

As the heroin moved to paralyse his lungs, he knew the narco warlords had won again. He knew his friend had been right, that was why the assassins had found him so quickly.

Race to the bottom

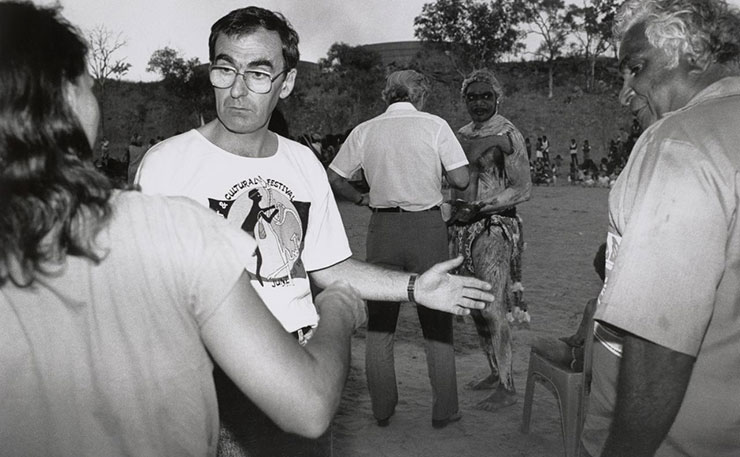

This re-enactment of Ali’s life and death at the hands of assassins working for narco warlords in Afghanistan and Pakistan was pieced together over many months. As a senior feature writer with the Australian Financial Review from 1996 to 2006, I covered the round of asylum seekers and refugees. During that time, like many who work and write in this field, I met people who had known Ali, his story and his struggles. I met many Hazaran and Iranian asylum seekers who had lived through Ali’s journey, with him for some of it, and who remain in Australia.

When I contacted the then Immigration Minister, Philip Ruddock, to ask why he had agreed to send Ali back knowing he was at risk, the minister’s spokesperson said that, in his opinion, Ali had died from a heart attack. Yes, he knew Ali had been found tied to a chair in a locked room, having had a hotshot of heroin, but his death certificate read “heart attack”. There was no question of refoulement – the universal term for when a country sends a refugee back to persecution and death – Ali was just an unlucky young bloke who had a weak heart.

By the time I left the Financial Review at the end of 2006, Australia’s position, policy and frame for asylum seekers had changed irrevocably. As this Refugee Council of Australia timeline reveals, we had become a nation that, according to a United Nations Report on Mandatory Detention, contravened the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. The report’s author, former Indian Supreme Court chief justice Rajendra Bhagwati, found children were suffering mentally and physically, and that many were “traumatised and led to harm himself or herself in utter despair”.

For those who had deep concerns about our treatment of asylum seekers, it felt like we had reached the lowest point – detaining and traumatising children, keeping refugees in limbo for years, sending refugees back to almost certain death and both major political parties using the spectre of refugees as a political opportunity rather than responding to it as a human tragedy.

We were wrong.

Over the past 10 years, Australia’s treatment of asylum seekers and refugees has become even worse. With no hope of policy change in sight, and with the situation unraveling out of control on both Nauru and Manus Island, it is time to ask ourselves how we got here and how we begin the long journey out of this political, ethical, legal and humanitarian quagmire.

How it all began

On 1 January 2016, the National Archives of Australia released selected key cabinet records for 1990 and 1991. One document, dated 26 June 1990, reveals the thinking that would later underpin the idea that people who arrived by boat were displacing refugees waiting in a refugee camp elsewhere in the world. This document introduces the idea of asylum seekers as “queue-jumpers”.

A background attachment prepared for cabinet explained:

Each applicant who is granted asylum in Australia displaces an applicant for humanitarian consideration overseas. Many applicants overseas are living in tenuous conditions in countries of refuge, have waited patiently in line to be assessed, and have claims for humanitarian resettlement which are far more urgent and compelling than the majority of cases considered in Australia. It added: We are seeing a growing trend worldwide of the jet-age asylum claimant.

However, it was 9pm on 30 March 1992 when a meeting took place between Labor’s then Minister for Social Security, Neal Blewett, the Minister for Aged, Family and Health Services, Peter Staples, and the Minister for Immigration, Local Government and Ethnic Affairs, Gerry Hand.

At this time, Australia had an unemployment rate of more than 11 per cent, was still struggling through a recession and had witnessed the transfer of prime-ministership from Bob Hawke to Paul Keating. Hawke had broken down in tears witnessing the destruction of the student protest in Tiananmen Square in 1989 and declared that all Chinese students currently residing in Australia could stay – permanently.

These were not easy times for the Keating government.

Nevertheless, the meeting was held to discuss asylum-seeker benefits: benefits that would be paid to asylum seekers as they waited for their claims to be settled.

At this point, asylum seekers coming to Australia could expect to be housed in the open village of Villawood, in Sydney’s western suburbs, with free access to English classes, Medibank, transport and trauma services. This meeting was set up to discuss the level of pension to be provided to asylum seekers and decide who would administer it.

Neal Blewett, A Cabinet Diary reads: “A 9 pm meeting with (Gerry) Hand and Staples on the asylum-seeker’s benefit. Hand wanted nothing to do with any ameliorative stance. He was for interning all who sought refugee status in camps, mostly at Port Hedland, where they would be fed and looked after. This is a nonsensical proposal – politically unsellable to the liberal constituency, impossible in practice (if any significant number of refugees took up the option his department would collapse) and financially irresponsible – if it worked it would cost more than the other options. It was obviously his (Hand’s) intention that if Staples provided an asylum-seeker benefit, or I the charity option or a modified asylum-seeker benefit, we would have to take responsibility for the measure. His left-wing mate Staples accused Hand of “abdicating responsibility for his own shit”. So Staples and I decided to call his bluff and accept his lead as Immigration Minister. It will be interesting to see the cabinet response to his proposals.”

Blewett didn’t have long to wait. Just six weeks later, on 5 May 1992, Gerry Hand introduced mandatory detention to Australia saying: “The Government is determined that a clear signal be sent that migration to Australia may not be achieved by simply arriving in this country and expecting to be allowed into the community… this legislation is only intended to be an interim measure. The present proposal refers principally to a detention regime for a specific class of persons. As such it is designed to address only the pressing requirements of the current situation. However, I acknowledge that it is necessary for wider consideration to be given to such basic issues as entry, detention and removal of certain non-citizens.”

There was no hue and cry over this announcement: it had bipartisan support and slid through to the keeper with almost no media coverage. But from this tweaking of the immigration system, much has followed. Certainly over the following 23 years, “much wider consideration has been given to such basic issues as entry, detention and removal of certain non-citizens”.

The introduction of mandatory detention was the stone that began the avalanche.

Australia has since become a nation that not only detains asylum seekers, but does so on the impoverished islands of Nauru and Manus Island.

Asylum seekers are held without charge, indefinitely. On these islands there are reports of systemic and routine sexual assault of women and children, of torture and bullying, of catastrophic mental health breakdowns.

The infamous Nauru Regional Processing Centre was opened in 2001 as part of the Howard government‘s Pacific Solution. It ran until 2008 when then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd closed the centre to fulfill his election promise.

However the Gillard Labor government re-opened the centre again in 2012. By 2013 conditions were so appalling it was being compared to a concentration camp.

In late 2015, Nauru and Manus Island featured as more than 100 nations queued up to ask Australia to rejoin the international community and end its harsh asylum policies.

When Blewett prophetically observed “if it worked it would cost more than the other options”, he could not have imagined a time when these harsh policies would cost about $1 billion a year to enforce – and that this $1 billion would go to a private company, not a public service.

The 2014 Commission of Audit’s report reveals that this offshore processing cost Australia’s taxpayers 10 times more than allowing asylum seekers to live in the community while their refugee claims are processed. It costs $400,000 a year to hold one asylum seeker in offshore detention; $239,000 a year to hold them in detention in Australia; and less than $100,000 for an asylum seeker to live in community detention.

It costs about $40,000 a year for an asylum seeker to live in the community on a bridging visa while their claim is processed.

Frames and counter-frames

The question of how Australia deals with people who arrive in Australia fleeing persecution has been framed in several ways over the past two decades. To understand how Australians got to the point where we now accept the brutalisation of innocent men, women and children to ensure they never arrive in Australia, we must look long and hard at the frames created by both major political parties. Because no issue in recent Australian history has been so tightly or skillfully framed as that of asylum seekers who arrive by boat.

While former Prime Minister John Howard (1996-2007) had come to power encouraging his fellow Australians to be “relaxed and comfortable”, it was clear by the turn of this century – and certainly post Tampa and 9/11 – that “alert not alarmed” suited his purposes better.

This was a time of vigilant alertness. It created a national disposition of concern or, as Ghassan Hage, professor of anthropology and social theory at the University of Melbourne called it, a “culture of worrying”.

During this time of “worry”, asylum seekers were labeled “illegals” and “queue-jumpers” – implying there was a well-ordered queue waiting somewhere in the world and asylum seekers should simply have joined it and waited patiently with the rest of humanity. Then they were referred to as “economic migrants” who were so rich they could use the services of people smugglers to jump the queue.

However, it was the hurried telephone conversation between the Commander of HMAS Adelaide, Norman Banks, and Brigadier Mike Silverstone on 7 October 2001 that delivered the Howard government an extraordinary opportunity. During that conversation Banks told Silverstone someone aboard what the navy called SIEV4 was threatening to throw a child overboard.

The “children overboard” claim emerged in the first week of the 2001 federal election campaign and, from the Coalition’s point of view, was simply “too good to be false”. In the lead-up to this incident, the Howard government had been running hard on “queue-jumpers” and the threat of terrorists arriving by boat – and, of course, preventing the Tampa from offloading its cargo of asylum seekers on Australian soil.

As has now become common practice, this event was dominated by the voices and moral evaluations of elite figures in the public service, the Defence Force and, above all, the government. This worked so well for the government in terms of keeping control of the narrative, it has now become a permanent fixture of the debate. Secrecy surrounds any incident at sea – every arrival, pushback, sinking and sighting of asylum seekers has become an “on-water matter”.

However, in recent years, the frame has changed yet again.

Early on the morning of 15 December 2010, a boat carrying 90 asylum seekers sank off the coast of Christmas Island: 48 people drowned and 42 were rescued. And all the while, horrific images of people getting pounded into the depths were beamed straight from the shore to our living rooms. The boat named SIEV-221 provided a powerful new frame.

Following this disaster, both Labor and Coalition politicians began arguing the brutal asylum seeker policies were necessary not so much to prevent queue-jumpers, terrorists or economic migrants, but to prevent drownings at sea.

It is worth noting the government’s frame has never been meaningfully challenged by a systematic, resourced and informed counter-narrative. For instance, in contrast to the refugee movement, the environment movement has spent the past six years putting serious financial resources into a national communications strategy that challenges the political, cultural and economic hegemony of the coal industry, with some outstanding successes.

Unfortunately, the refugee movement continues to forgo the alliance-building work necessary for such an approach with the result that the narrative stays firmly in the grip of the major political parties.

Indeed, both Labor and the Coalition argue the policies have been successful. The boats have essentially stopped coming to Australia and therefore people are no longer drowning at sea.

This is the big lie.

People are still drowning at sea, but now they are drowning in a different part of the sea – no longer the Indian Ocean so much as the Andaman Sea.

In 2014, asylum seekers drowned well outside Australia’s territorial waters. Further, pushing back the boats of those fleeing persecution simply means these people will die or be tortured when they return to the country they are fleeing – that’s why they took such a perilous journey in the first place.

The extreme nature of the boat turnbacks strategy was revealed to the world in a speech by the former Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, to an audience of Conservative British MPs.

“No country or continent can open its borders to all-comers without fundamentally weakening itself,” he said. “Too much mercy for some necessarily undermines justice for all.”

Like a lightning strike briefly illuminating a darkened landscape, that speech showed the world just how low Australian politics had sunk, with one Tory MP referring to the speech as “fascist”.

The frame for the debate is not the only aspect that has changed. Asylum seekers and refugees living in Australia’s camps on Nauru and Manus Island are experiencing shocking treatment – even by Australia’s appalling standards. Nauru has essentially become a black site where accountability has completely broken down.

During the most recent Senate Inquiry into Nauru’s detention centre, Greens Senator Sarah Hanson-Young, deputy chair of the report’s committee, pointed to what she called the “mountains of evidence” that abuse is widespread in the centre.

“The most horrific aspects of this inquiry really are the abuse of children, the sexual harassment and assault of women,” Senator Hanson-Young said. “And the fact that for months, the government contractors have known that this abuse has been going on and yet these women and children remain locked up inside the camp.”

Nor are refugees safe once they leave the camps. Late in 2015, The Saturday Paper revealed the fate of one young woman who lives at the mercy of guards and locals on Nauru. The headline read: “Nauru rapes: There is a war on women”.

Following the publication of that story, I worked with the campaign co-ordinator at the Asylum Seeker Resource Centre, Pamela Curr; former West Australian premier Professor Carmen Lawrence, journalist, activist and New Matilda Associate Editor Professor Wendy Bacon, Claire O’Connor SC, and communications specialist Luisa Low to form a group called Australian women in support of women on Nauru.

The group’s objective is simple: with Nauru charging a non-refundable $8,000 for a media representative to apply for a visa to the island, we would crowd-source the fee, take the risk and apply to have Bacon then Lawrence go to Nauru on a fact-finding project.

After Bacon applied, Nauru’s Justice Minister, David Adeang, announced all foreign journalists were banned from the island – at which point O’Connor stepped in and also applied for a visa.

It is clear Nauru will not allow any members of our group – or any other group from civil society or the media – access to the island.

News Limited journalist Chris Kenny is an exception to this ban. Kenny himself believes he was allowed on Nauru recently in part because of his support for the current policy settings: “If my public support for strong border protection measures helped sway Nauru’s decision, so be it,” he said.

Late in 2015, charity organisation Save the Children was also sent packing. After this the Nauruan police instituted a regime of strip-searching – particularly of women – to uncover mobile phones. As one woman living on Nauru told an advocate: “These are the humiliations we live with. They laugh and sneer at us when they make us take off our clothes.”

Nauru has become Australia’s very own black site. Predictably, the lack of accountability is leading to even greater abuses, according to several advocates who manage to stay in contact with asylum seekers and refugees on the island.

With a media blackout on interception at sea and access to Manus and Nauru nearly impossible – not to mention the new Border Force Act that effectively gags doctors and healthcare workers reporting on conditions in these camps – the reality of life and inherent humanity of asylum seekers in these camps is totally denied.

Their stories are whispered to the few lawyers, doctors and reporters who find a way to get a phone call through or who have relationships within the Hazaran, Iranian, Iraqi and Syrian diaspora.

But change is in the air.

High cost of harm

As news crews from around the world descended on Greece in 2015, and on checkpoints in Hungary, Croatia, Germany and Austria, we had our noses pressed up against the picture of refugees fleeing the war in Syria. When we watched the policeman gently scoop up the body of little Aylan Kurdi from the shores of Turkey, our own broken humanity was briefly lit in stark relief.

We know that half of Syria’s population of 8 million is dead, displaced or fleeing – not even Australia can ignore that reality.

As the international community grapples with the complexity of record-breaking flows of people across Europe, Australia’s asylum-seeker policies look brutal and stupid. This is why United Nations officials had to limit countries to speaking for just three minutes when it came time for Australia’s Periodic Review – more than 100 countries had lined up to tell Australia where it was going wrong on its asylum seeker policy.

This policy is costing nearly $1 billion a year – not including the costs of the Navy and Coast Guard. It is costing Australia hard-earned political capital internationally; it is costing the women on Nauru their safety and sanity.

The weight of Australia’s detention centre is tearing at the wafer-thin fabric of Nauru’s democracy. The detention centre on Manus Island continues to see riots, hunger strikes, despair and death.

Perhaps of greater concern to both Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Opposition Leader Bill Shorten, the polls are shifting. A poll taken shortly after the world became aware of little Aylan asked Australian voters whether they supported Operation Sovereign Borders, which includes turning back boats and offshore detention of asylum seekers: 54 per cent said they backed it and 46 per cent were opposed.

This compares to a Lowy Institute poll taken last year that showed 71 per cent of those surveyed backed the policy of turning back boats.

We have a new Prime Minister. We have an historic moment – a window of opportunity to change the way we deal with the world’s most vulnerable people.

The journey to Nauru and Manus Island took more than 20 years. With annual adjustments and an unchallenged national narrative, we have arrived at a place Neil Blewett and his colleagues could not have dreamed possible in 1992. It need not take us another 23 years to find our way back to a humane, sensible asylum-seeker policy.

The way out

We need to do three things. First, grant amnesty to all those currently held on Nauru and Manus Island and bring them to Australia. That’s less than 2,000 women, children and men.

Second, cancel the contracts for Transfield and Wilson Security and begin the diplomatic, legal and financial work necessary to implement a safe, secure and long-term regional solution. This means redirecting the billions of dollars currently being spent on Nauru and Manus Island to meaningfully resourcing the UNHCR in Indonesia and Malaysia.

Contrary to popular belief, most refugees only look to resettlement when home is no longer safe and the place they are in is too inhospitable. We need to support and resource “transit” countries to enable the fast, fair and equitable processing of refugees.

Third, Australia needs to increase its intake of refugees from these newly resourced assessment centres in Indonesia and Malaysia.

However none of this will happen until the dominant narrative around asylum seekers and refugees is successfully challenged. When I first began covering this round at The Financial Review a former shadow Immigration minister outlined the dynamic in simple, brutal terms saying: “Getting tough on asylum seekers is like shooting fish in a barrel.”

Those concerned about Australia’s treatment of refugees and asylum seekers need to get smart about creating a counter narrative to the current story of fear, distrust and inhumanity. By changing the frame to one of shared humanity, success and courage, it becomes harder for politicians from both major parties to get political mileage out of brutalizing them.

This is not brain surgery. This is how we build a culture in which violence against women is eradicated in Australia and on Nauru, where difference is celebrated and where an Australian accent is once again welcomed around the world. This is how we recover our own humanity.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.