Australia’s role in the invasion of East Timor remains part of the unfinished business of our nation. But our current determination to lock the East Timorese out of billions of dollars in gas and oil revenue is happening right now. Peter Job explains.

In early October the Timor-Leste Prime Minister Rui Maria de Araujo announced that after two years of inconclusive talks his nation was initiating arbitration with Australia on jurisdiction concerning seabed resources in the Timor Sea, which he described as, “an issue of sovereignty and an issue of justice”.

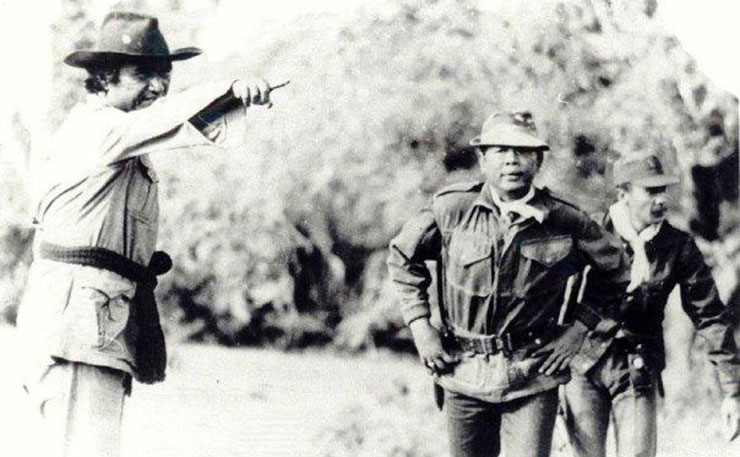

This month Xanana Gusmao declared that Timor-Leste would appeal to Australians’ sense of fair play to push their government into meaningful talks. With the issue central to Timor-Leste’s future, it is worthwhile looking at how Australia’s behaviour in the past has impacted on the Timorese people.

In the National Archives of Australia earlier this year I came across an extraordinary document. Entitled, Steps to Prevent Communist Agitators to Escape it appears to be a ‘hit list’ of prominent Timorese leaders prepared by the Indonesian authorities in August 1975, in the lead up to the invasion.

Its list of 19 so-called, “suspected communist agitators” includes Nicolau Lobato, the Fretilin leader and President of the republic who was killed by Indonesian forces in 1978; Jose Ramos Horta, who in exile led the struggle for his nation’s liberation and earned the Noble Prize for Peace for doing so; Antonio Carvarino, the Fretilin leader and writer who was killed by the Indonesian military immediately upon his capture in February 1979; and Rosa Muki Bonaparte, secretary of the Popular Organisation of Timorese Women, executed by Indonesian forces upon her capture the day after the invasion on 8 December 1975.

The handwritten document urges measures be undertaken, “to avoid the escape of communist guilt leaders”, making specific allegations against Fretilin members concerning links with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) and various communist countries.

The allegations are not supported by evidence; even the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) assessments at the time concluded Fretilin was a fundamentally nationalist non-communist movement, and links between it and a by then almost completely defunct PKI are not documented.

The document was handed to Australian diplomat Alan Taylor by Indonesian intelligence operative Harry Tjan in early September 1975, some two and a half months before the invasion.

Taylor’s covering letter indicates that it was forwarded to the DFA Secretary Alan Renouf. There is no further documentation relating to it, no evidence that it became a subject of policy discussion and certainly no evidence that concerns were raised about it with Indonesian authorities.

This matter can be understood in the context of a series of briefings provided by Indonesian intelligence operatives in the year and a half before the invasion. Officials from the intelligence organisation OPSUS approached officials at the Australian embassy in Jakarta in July 1974 to inform them they intended to mount a clandestine operation to ensure East Timor became part of Indonesia.

The many briefings that followed were remarkably candid, outlining activities ranging from radio propaganda to the training of pro-Indonesian forces to destabilise East Timor to produce a pretext for intervention.

The Australian officials who heard, documented and learned of them were also remarkably compliant in failing to express concern, an attitude that would have encouraged the hardliners in the Suharto regime pressing for invasion.

At the instigation of Indonesian intelligence, the conservative East Timorese party UDT instigated a coup in August 1975. Fretilin responded with a call to arms, and after a brief civil war gained control of the territory. Having had its hand forced, but still seeking orderly decolonisation, Fretilin then called for a Portuguese return and international assistance to support a legal decolonisation process to avoid the Indonesian invasion they feared was coming.

The Indonesian intelligence services with which DFA officials were cooperating acted somewhat differently.

OPSUS briefings during this period informed Australian officials of the arming and training of anti-Fretilin forces in West Timor, the infiltration of thousands of Indonesian army regulars disguised as Timorese forces as well as prior warnings of specific Indonesian military operations, including the attack on Balibo which claimed the lives of five Australian-based journalists.

Meanwhile to the Australian public and international community, Australian representatives told a very different story. When Jose Ramos Horta visited Australia in December 1974, DFA officials told him Indonesians had assured them they would, “scrupulously respect the outcome of an act of self-determination”.

Whitlam’s principal private secretary wrote to the Fretilin and UDT leadership in March 1975 stating that reports of plans for military action had been denied by the Indonesian government and that, “the Australian Government… was glad to receive this confirmation from the Indonesian authorities”.

Whitlam informed the House of Representatives in August 1975 that Indonesian leaders had, “denied that Indonesia has any territorial ambitions towards Portuguese Timor”. He wrote to the Secretary of the Waterside Waters Federation in September 1975 stating that Suharto, “has been clearly and strongly committed to a process of peaceful decolonisation” and had “thus far…exercised considerable restraint”.

Such phrases and sentiments were echoed by DFA officials in their responses to public concerns.

As one Australian diplomat pointed out, the briefings were a form of consultation. Through their acquiescence Australian representatives from the highest levels down effectively gave their assent. Through their public denials they took this a step further, lying to the public and the international community about what they knew, becoming instruments and propagandists not only of the Suharto regime, but of the particular faction within it most bent on undermining the Timorese decolonisation process, if necessary through subversion and violence.

Nor was this process an empty inquiry on the part of Indonesian intelligence. The evidence indicates that the Suharto regime was highly conflicted about its intentions regarding East Timor, with deep concerns from some, including Suharto himself, about the impact an Indonesian invasion would have on Indonesia’s international standing.

Australia’s continued acquiescence – and at times outright encouragement – of Indonesian intervention throughout the year and a half prior to the invasion would have been a strong factor in the decisions to engage in such activities, and in the final decision to invade.

The action of an Indonesian intelligence officer in translating this document into English and providing it to an Australian diplomat can be understood as a form of consultation – an attempt, and a successful one, of producing Australian complicity with planned Indonesian actions.

Twenty-four years of Indonesian occupation, effectively supported for most of this time by a series of compliant Australian governments, left the economy and infrastructure of the nation devastated and created a death toll that credible demographic analysis puts in the hundreds of thousands.

Timor-Leste today is an independent nation and a parliamentary democracy, yet it remains one of the poorest nations in Asia. More than anything its future will depend on a just and equitable settlement of the maritime boundary.

Since Timor-Leste’s independence, Australia has worked against this, withdrawing from jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice, spying on the Timor-Leste cabinet room during the negotiation process of the resources treaty and using what it learned to force an inequitable outcome, even later raiding the offices of Timor-Leste’s barrister and seizing documents.

A settlement of the boundary based on a midway point, as was the ALP position in 2000, would have meant billions of dollars of oil and gas revenue flowing to Timor-Leste that has since gone to Australia, dwarfing the comparatively small amount of aid we have provided.

We cannot turn the clock back to 1975. But an equitable settlement of the Timor Sea boundary based on international law will at least provide the Timorese people the opportunity to move forward into a stable economic future.

Given our history it is the very least the Australian people should demand of their government.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.