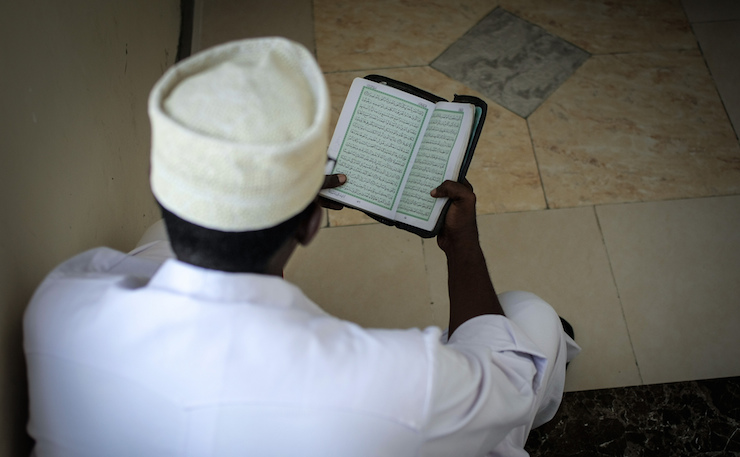

The Qur’an has some pretty violent passages. And then there’s the Bible. Megan Giles breaks it down.

It pains me to have to acknowledge the words of Pauline Hanson, the befouled splatter on Australia’s underbelly that represents all the very worst aspects of our social frailties.

Until recently, for myself at least, Hanson was largely a forgotten blip from the politics of the 1990’s who, although commanding a relatively peripheral legion of supporters, was mostly seen as the butt of our national jokes; quickly passing her prime and subsequently popping her head up every now and again to spew some inarticulate, divisive and bigoted tirades before disappearing back into her insignificance until she decided to bother us again.

Though recently Channel Nine’s Today show did decide it would be a good idea to seek Hanson’s wisdom following last week’s Paris attacks.

During the interview, an exasperated Hanson thought it meritorious that she had demanded a random Muslim taxi driver she encountered somehow take ownership of Islamic State’s actions and professed that until he, the lone, utterly disconnected individual on the other side of the world just trying to make a living “stands up and says ‘We condemn this’ then…. [something, something, incoherent ramble]”.

Not before referring to Islamic teachings as “tentacles” and appearing baffled that Muslims who condemn Islamic State do not leave their religion, did host Cameron Williams thank her for her thoughts as they are “always welcome at home”.

Back in October, the Today show gave Hanson the microphone to explain her insufferable campaign against ‘No more mosques, sharia law, halal certification and Muslim refugees’. To his credit Karl Stefanovic did slightly challenge Hanson’s views at some points through-out their interview, albeit punctuated with some ego-stroking, jovial banter.

Perhaps he was clever enough to save his own hide by at least appeasing the rational viewers at home.

Hanson’s words during that interview are worthy of mention, since they represent such fundamentally wrong interpretations of terrorism and forge a discussion that fails to acknowledge and address the crux of it.

After all these years, since 9/11 and Bush’s War on Terror, we are still blaming Islam. Still quoting verses from an ancient book as if it alone compels its readers to strap themselves with explosives and take themselves and innocent others to an early grave. As though it were so drastically more violent than other Abrahamic texts.

Hanson states that the New Testament, unlike the Qur’an, is devoid of any violence, as if the relative peace and prosperity enjoyed by the Western world is somehow solely attributed to the teachings of Jesus Christ.

I can tell you right now that Christianity did not contribute to making me a moral person. Nor do I believe it had such a make or break impact on the Australian way of life.

Hanson and many others fail to recognise the context of time, place and circumstance that permits the usurping of Quranic verses for such violence.

They fail to scrutinise what it is that separates the millions of Muslims, and millions of others of faith, who can read their sacred scriptures in their historical contexts, from those that totalise and literalise religious doctrine and wrongly champion it as the impetus for their savagery.

Failing to miss what it is that separates these two groups means we fail to address what makes an individual ‘radicalise’ in the first place. The social, political and economic reasons individuals are so significantly marginalised, angered and ostracised that they seek solace in death, and not life. In war, and not peace. We therefore fail to find any meaningful solution, since we too often look in the wrong places.

If we want to scrutinise religious doctrines, then we must be prepared to thoroughly scrutinise them all. Like the Old Testament, the Qur’an does contain some pretty violent text.

Professor of Middle Eastern history at the University of California, Mark LeVine recently noted, “The problem with critics of Islam like Bill Maher and Richard Dawkins is not so much that they are wrong about Islam as much as that they assume Islam and Muslims are somehow unique in their prejudices, chauvinism and violence,” citing the Israeli occupation of Palestine, Hindu-led violence in India, a long history of Christian crimes, and exhaustless numbers of death throughout history attributed to the building of ‘nationhood’ and “untrammeled capitalism”.

Hanson clumsily quotes the Quranic verse 4:89, “They wish you would disbelieve as they have disbelieved you so you would be alike. So do not take from among them allies until they emigrate for the cause of Allah. But if they turn away, then seize them and kill them wherever you find them…”

Like many critics of Islam, Hanson conveniently leaves out the next passage (if she’s even aware it exists and I’m not sure which is worse).

Verse 4:90 outlines conditions for mercy, “…And if Allah had willed, He could have given them power over you, and they would have fought you. So if they remove themselves from you and do not fight you and offer you peace, then Allah has not made for you a cause against them.”

Distinguished Professor of History, Philip Jenkins has noted his surprise that the Qur’an is actually far less bloody than the Bible.

“By the standards of the time, which is the 7th century A.D., the laws of war that are laid down by the Qur’an are actually reasonably humane… Then we turn to the Bible, and we actually find something that is for many people a real surprise. There is a specific kind of warfare laid down in the Bible which we can only call genocide.”

Professor of International Affairs and Islamic Studies at Georgetown University, John Esposito states that the early Qur’an does not condone “illegitimate” violence but permits Muslims to respond to aggression and injustice in their duty to lead a virtuous life, or jihad.

More militant ‘sword verses’ were reinterpretations of the Qur’an by late eighth/ early ninth century religious scholars to justify imperial expansion.

In the late 20th century, regimes across the Arab world shaped and utilised Islamic ideologies to solidify and mobilise support against Western liberalism. And so it goes, on and on through history. Past contexts magically transforming to suit present and future contexts.

When we place blame we go directly to the original source, without acknowledging how that source has been manipulated to accommodate contemporary political objectives.

Though all of this, in our current debate, is near-irrelevant. Focusing on the details of religious texts will lead us nowhere since we have, right in front of us, countless examples that help us understand the rise of Islamic State and specific historical, albeit complex and multi-faceted, justifications for North African and Middle Eastern violence.

Indeed what is missing from mainstream debates about contemporary terrorism is the very heavy historical baggage it carries.

Tony Blair has apologised for “mistakes” made during the 2003 invasion of Iraq. The US government’s hasty state-building policies after the disbanding of the Iraqi army left thousands of young men angry, armed and unemployed.

Unfortunately, only few commentators will reach back far enough into history to examine the brutal, incendiary and utterly destructive legacy of colonialism in the Middle East to understand contemporary violence.

While ‘we’ in the West have moved on from colonialism and want everyone else to just ‘get over it’, post-colonial states were never given space to – they live its continuity in the neocolonial economic policies of the Washington Consensus and the ubiquity of a militarised national consciousness where violence pervades and reproduces.

The late Algerian psychiatrist Franz Fanon has written passionately on the impact of colonialism on the colonised individual’s psyche, and its propensity for creating violent separatist and regionalist factions, long after independence.

“At the individual level, violence is a cleansing force. It rids the colonized of their inferiority complex, of their passive and despairing attitude… Violence hoists the people up to the level of the leader.”

Despite the horrors of history committed on every continent, our right to anger and grieve over the bloodshed in Paris is doubtless. It must be denounced with the loudest possible voice and responded to with the strongest possible deliberation and vigilance.

Good people lost their lives because they represented the freedom we all hold dear, no matter our race, nationality or religion. Though we must fall short of dismay that Middle Eastern wars have somehow spilled over onto a bystanding Europe caught up in the crossfire.

These wars belong to the Great Powers and they always have. As Gordon Adams has noted, “France has been a central arena for the confrontation between Islam and political-religious Christian Europe for 1,300 years.”

The proceeding centuries were characterised by a vicious brand of colonialism under the guise of exporting a concept of citizenship that was highly exclusionary at home, and anti-Islamic domestic policies leaving hostility an omnipresence weaved through France’s social and political fabric.

Adams states, “France needs to undergo a deep self-examination, and a fundamental revision of the current practice of sidelining its large Muslim population, leaving them disaffected, poorly educated, underemployed, and ripe for recruitment to terrorism.”

All religious texts have the capacity to unite or divide humanity. Our conversation must start centering on the dark, ugly side of human nature and the contexts that breed violent extremists of which our own states are often complicit in.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.