Marine conservationists at Sea Shepherd have challenged whether the huge ecological by-catch of Queensland’s program to protect swimmers from sharks is worth it. Thom Mitchell reports.

Sea Shepherd has attacked the Queensland Shark Control Program which it says is a clumsy and ultimately unnecessary attempt to protect swimmers that is resulting in the ‘fishing down’ of environmentally important populations of the apex predator.

The NGO has engaged a fourth year Harvard University student, Carolyn Pushaw, to analyse reams of catch-data obtained under Freedom of Information legislation which reveals the ecological carnage of the state’s shark control regime.

In total, more than 8,000 marine species with some level of protection status have been caught by the Queensland Shark Control Program, including 719 loggerhead turtles, 442 manta rays and 33 critically endangered hawksbill turtles.

More than 84,000 marine animals have been ensnared by drum-lines and shark nets since the program began in 1962. According to Sea Shepherd’s National Shark Campaign Coordinator Natalie Banks, of the 54 shark species captured “most are not a threat at all to ocean users”.

Even if these sharks are considered by-catch, Sea Shepherd said, nearly 27,000 marine mammals have been snared. The state’s shark control policy has captured over 5,000 turtles, 1,014 dolphins, nearly 700 dugongs and 120 whales, all of which are federally protected marine species, according to Sea Shepherd.

“The Queensland shark program was the best solution 50 years ago, but it’s not today,” Pushaw said. “Basically in the early 1960s there were two fatal shark attacks in Queensland which led to calls to protect the beaches… so what they did was use essentially what are fishing nets and fishing lines.

“The program is designed to catch and kill dangerous sharks and as we can see from these numbers it seems to have done a pretty good job.

“There’s a list of target sharks… and when those are found caught in the net they shoot the sharks and dump their bodies off the coast.

“If it’s a non-target species, unfortunately many of them die before the nets are checked every two days.”

The Manager of Fisheries Queensland’s Shark Control Program, Jeff Krause, said “the Program is not designed to reduce the shark population in Queensland waters”. And given it only operates on around half a per cent of Queensland’s coastline, he said it’s “highly unlikely to impact upon the sustainability of any shark population in Queensland waters”.

But Pushaw argued that while it’s difficult to source accurate data on overall shark populations, “it’s likely there are multiple different factors that are reducing shark populations, and that the Queensland shark catch program is among those factors”.

In the absence of a finning trade, and in light of the fact commercial fishers don’t target sharks, she said, “the shark program is one of the main sources of fishing down sharks in the region”.

“It’s capturing pretty significant numbers of sharks, especially from threatened species. For example, with an estimated population perhaps as low as 1,000 Grey Nurse sharks left off the east coast of Australia, even a catch of five sharks a year is pretty significant in terms of that population.”

Sea Shepherd Campaigner Natalie Banks said it is “stomach-turning” that 265 critically endangered Grey Nurse sharks have been snagged by the Program.

According to the figures obtained by Sea Shepherd the program has also resulted in the capture of 310 Dusky Sharks and 265 Sandbar Sharks, both rated as vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

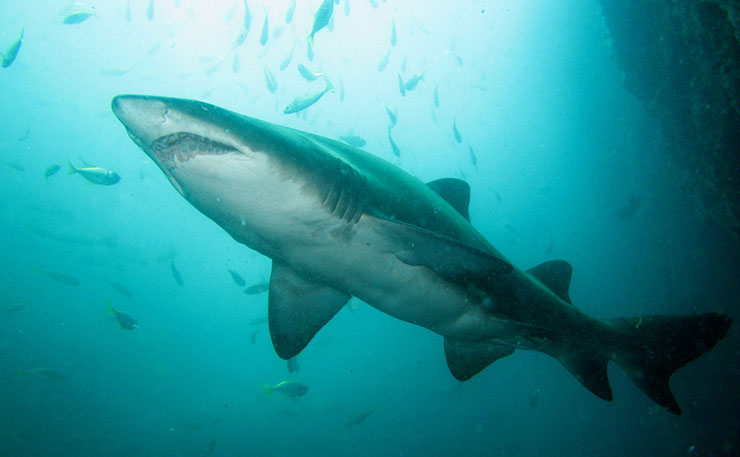

Sharks perform important ecological functions maintaining population numbers of other species down the food chain, through their place as the ocean’s apex predator, and a decline in their population, would have serious flow-on affects.

Despite the heavy environmental cost, Krause said the “Program is effective in reducing the overall number of sharks in an area, making it a safer place to swim”.

“The success of the program is highlighted by the fact that there has been one shark attack recorded at a shark control beach since its introduction in 1962,” he said.

“Queenslanders want to be able to enjoy swimming at our beaches and human safety must come first. That’s why we’re committed to this program.”

It’s a claim that’s contested by Professor Jessica Meeuwig, Director of the University of Western Australia’s Centre for Marine Futures, who wrote last year that drum lines are a “blunt instrument” and their effectiveness is “difficult to evaluate”.

“The rates of attacks before and after their deployment are both very low,” she said. “Moreover, its success in reducing human fatalities is hard to validate. The decreases may simply reflect broader declines in shark populations, driving down encounter rates despite the increased human presence in the ocean. Or they may simply be random.”

In contrast, “the ecological cost of drum lines is high, with 97 per cent of sharks caught since 2001 considered to be at some level of conservation risk [and]89 per cent were caught in areas where no fatalities have occurred”.

There was a review of the Program last year, and Krause said that as a result “an additional 16 shark species were added to the list of non-target species”.

He detailed a wide range of less invasive shark control measures that have been explored or trialled, but said that “traditional control methods remain the most effective means of reducing the risk of shark attack”.

The effectiveness of alternative control mechanisms is contested, but shark expert Dr Jonathan Werry agrees with Krause. “The reality is that there’s no proven technology that can satisfy sufficient safety for people at this stage,” he said.

“The problem is [that]sharks learn… Particular technology that may deter an animal may not work for that same animal in the future, so you always have to keep the shark guessing.”

For a short time earlier this year, residents of New South Wales were left guessing at whether the state would introduce a shark cull in the wake of an unusual spate of attacks, but Premier Mike Baird has ruled that out.

“I want you to know we are doing what we can to take measured and effective action to keep our beaches as safe as we can,” Baird wrote in a Facebook post in August. “But it will be done based on fact, not emotion.”

According to an annual tally kept by Taronga Zoo, in 2014 shark attacks caused five fatalities in Australia.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.