The dialling down of the rhetoric is welcome, but will there also be a new narrative, asks Nick Pendergrast.

On Friday, Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull gave a press conference on countering violent extremism. It came in the wake of the recent Parramatta shooting, where 15-year-old Farhad Habar shot and killed police employee Curtis Cheng, before being shot dead himself by police.

Turnbull told media “everything I do as your Prime Minister is designed to make us safe”. He went on to celebrate the success of multiculturalism in Australia and argue that “mutual respect is fundamental to our harmony as a multicultural society” as well as to our national security.

According to research on counter-terrorism, Turnbull’s embracing of multiculturalism and mutual respect is indeed likely to make Australians safer.

A New Approach

In his comments following the Parramatta shooting, Turnbull has made a point to differentiate the actions of Farhad Habar from other Muslims. Such comments included: “We must not vilify or blame the entire Muslim community with the actions of what is, in truth, a very, very small percentage of violent extremist individuals.”

Dr Jamal Rifi, an Australian-Lebanese Muslim GP has welcomed this new approach from the Australian government, arguing they are a ‘quantum leap’ from its previous approach. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott’s “Team Australia” rhetoric was indeed very different – adopting more of “guilty until proven innocent” mentality towards Muslim people, reflected in his suggestion that Muslim leaders should proclaim Islam as a religion of peace “more often, and mean it”.

Soft Strategies against Terrorism

In their book Global Terrorism, James Lutz and Brenda Lutz argue that repression and discrimination, real or perceived, provides a “fertile ground” in which terrorism is more likely to occur. Turnbull’s efforts to not demonise Muslim people as a whole are consistent with attempting to avoid creating such an environment.

Counter-terrorism expert Dr Anne Aly argues that “hard” tactics such as increased powers will not be successful unless they are complemented by other “soft” strategies. Such strategies involve stopping terrorism at is roots by addressing the conditions that make violence appealing, rather than simply trying to stop these actions once someone has decided they want to carry them out.

Challenging Dominant Narratives?

While Turnbull’s response has been an improvement in addressing the root causes of terrorism, he has failed to challenge dominant narratives on terrorism. Following the Sydney Siege, sociologist Randa Abdel-Fattah, whose research focuses on Islamophobia in Australia, asked whether Australian Muslims “will be entitled to grieve the deaths of the two hostages and the trauma suffered by the survivors in a way that does not make their empathy and grief contingent on condemning, apologizing and distancing themselves from the gunman.”

Turnbull’s rhetoric has certainly not asked Muslim people to apologise for the actions of the Parramatta shooting, but even while speaking about Muslims in a more positive way, he has still framed the violence as something for the “Muslim community” to address.

Following the Parramatta shooting, Turnbull stated: “The Muslim community are our absolutely necessary partners in combating this type of violent extremism.”

The notion of the “Muslim community” is contested. Comments along the lines of ‘what does the Muslim community think of the attack?’ or ‘when will the Muslim community condemn the attack?’ often assume a monolithic community, when people of Muslim faith in Australia may not have any connection to each other besides sharing the same religion.

They may also identify more along ethnic than religious lines, and like any other religion, vary widely when it comes to political views.

The Charleston Shooting and Responses to White Violence

Putting that aside, this responsibility placed on Muslims is not a burden faced by some other groups. Never was this clearer than after the Charleston shooting in the US, where white supremacist Dylann Roof killed nine people at an historic African-American South Carolina church in an act of politically-motivated violence.

Not only did most of the media refuse to label the act as terrorism, but the response to the violence was also very different. Whereas Roof was dismissed as a mentally ill lone wolf and just ‘one hateful person’, journalist Anthea Butler argues that violence by Muslim people is portrayed as “systemic, demanding response and action from all who share their… religion”.

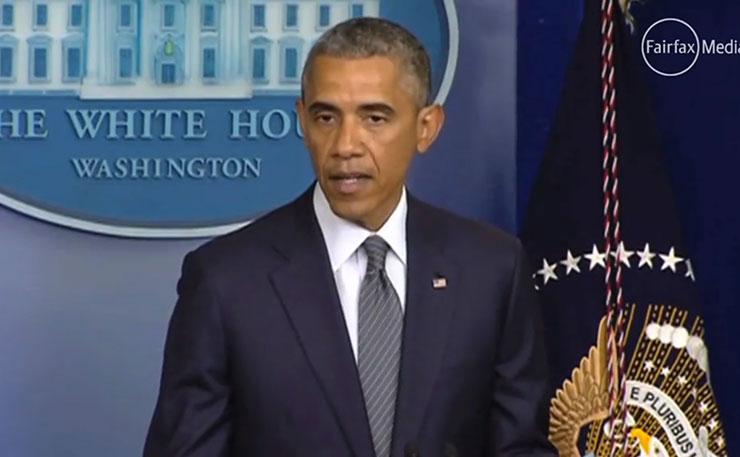

Journalist Solomon Comissiong explained that US President Barack Obama didn’t mention race after the Charleston shooting and instead framed the issue in terms of a lack of gun control. Comissiong also pointed out that after the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing by two white men, Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols, there was no racial profiling or harassment of white men of certain ages, and the same was true after the Roof shooting.

In an Australian context, Abdel-Fattah outlines many recent acts of violence in Australia by non-Muslims, including hostage taking and firebombing, that have not been labelled as terrorism and have also not led to a systematic response. Violence by Muslims has a very different narrative.

This is a narrative that Turnbull’s response has not challenged. His reaching out to Muslim leaders straight after the Parramatta shooting, involving actions such as phone conferences, still frame violence by one Muslim as something that demands response from other Muslims. This is in contrast to violence by white non-Muslims, which is only seen as deserving an individualised response.

Turnbull’s more inclusive rhetoric following the Parramatta shooting is an improvement of Abbott’s “Team Australia” mentality, and is indeed likely to make Australians safer than previous responses.

While acknowledging these positives, it is also important to look critically into dominant Western narratives on terrorism.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.