Whatever would have happened with the Government’s leadership, it was inevitable that Labor would make political capital out of Abbott’s claim to be “the infrastructure prime minister”.

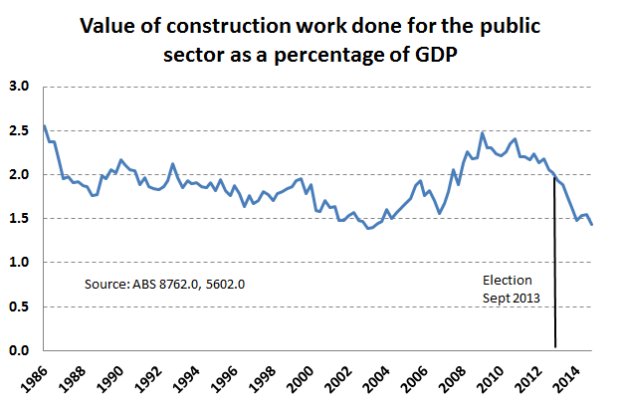

Readers of the Murdoch media may not have noticed there has been a huge fall in government infrastructure spending since the Coalition was elected two years ago (see the graph below). At 1.4 per cent of GDP it is now as low as at any time over the last 40 years – a reflection of the fact that two Coalition budgets made hardly any commitment to infrastructure.

But as commuters know through uncomfortable experience, be they users of roads or public transport, we have a huge deficit in transport infrastructure. The Commonwealth Government estimates the annual costs of urban traffic congestion, just one consequence of inadequate infrastructure, to be around $16 billion a year, rising to $20 billion by 2020. And by international comparisons we rate poorly. Infrastructure Australia reports that almost every other developed country (even the USA) ranks above Australia in infrastructure adequacy.

Turnbull’s softening on the Coalition’s previous refusal to support public transport seems to have pushed Labor into a hasty release of its priorities, outlined in Shorten’s speech to the Queensland Media Club on Thursday.

Labor’s list of priority projects aligns with what we know about areas of need. It covers public transport in urban areas (cross-city rail in Brisbane, light rail on the Gold Coast, rail for Sydney’s new airport, new rail lines for Melbourne, electrification of the Adelaide northern line), and non-urban roads (the Pacific Highway in NSW, the Bruce Highway in Queensland and the Midland Highway in Tasmania).

What stands out is the modesty of Labor’s proposals. There are many more areas of need, mainly in urban public transport, interstate road and rail, and urban freight roads. And that’s not to mention high-speed intercity rail – perhaps Labor has lost the self-confidence even to mention projects that may excite the imagination.

It seems Labor has been spooked by a fear of debt – or, more precisely, the way the government would represent debt finance as being economically irresponsible. Shorten shows he understands the economic case for debt finance, making “a significant – and very real – distinction between debt raised for capital expenditure and debt raised for recurrent expenditure”, but he acknowledges the risk of “a scare campaign about debt.”

So he has been vague about funding. His only specific funding commitment is to set up Infrastructure Australia with a $10 billion fund ($6 billion from Commonwealth borrowing, $4 billion transferred from the Building Australia Fund), to allow it to act in a way similar to the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, leveraging private sector finance for a portfolio of investments.

That may be a worthwhile initiative, but $10 billion won’t go far – perhaps one significant underground metro project, or 200 km of freeway along the difficult terrain of Australia’s east coast.

More basically, unlike the projects supported by the Clean Energy Finance Corporation, the projects we need aren’t amenable to private funding, because while they give a return to the community, they do not give a return to any private investor. Lest that sounds radical, we can call on that champion of the free market, Adam Smith, who wrote in The Wealth of Nations:

The third and last duty of the sovereign or commonwealth is that of erecting and maintaining those public institutions and those public works, which, though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals, and which it therefore cannot be expected that any individual or small number of individuals should erect or maintain.

There are places where toll roads can be built, but there’s no way, with present technology, tolls could be applied on our non-urban roads such as the heavily-used Pacific, Bruce and Midland Highways, or the bone-shaking roads in the outback. And in any event, it’s a severe distortion to have tolls on an otherwise free road network. Smith would be horrified to learn how we have funded our urban road projects over the last few years.

A case in point, familiar to many readers, is Sydney’s cross-city tunnel, with tolls of $5.27 for a car and $10.54 for a truck. At most times of day it’s as quiet as a suburban street – you could safely play a game of cricket in it – while the streets above are often gridlocked. Any reasonable person, including an eighteenth century economist, would conclude that the tunnel should be free while a prohibitive toll should be applied to those who choose to clog up the surface streets. (Economists know this phenomenon of misallocation because of poor pricing as “deadweight loss”.)

Rather than getting the private sector to build the occasional toll road or new subway line, it’s much cheaper and more efficient for governments to finance roads and public transport through borrowing, taking advantage of the low interest rate on government bonds, rather than relying on expensive gimmicks like PPPs and tolls. As an analogy, if you need to invest in a small business, you don’t borrow on your credit card at 20 per cent interest if you have the option of taking a loan at 10 per cent.

An easy way to service government debt used to fund roads is with a higher fuel tax. Most prosperous countries impose a tax of between $1.00 and $1.60 a litre on automotive fuels, but Australia’s tax (including GST) is only 42 cents a litre. Each additional cent would raise about $400 million in public revenue. Besides raising revenue for roads, a higher price would divert some road users to public transport, thereby relieving congestion and providing more revenue to cover the fixed costs of public transport. In time, of course, technologies should allow for comprehensive road user charging.

But the more general point, emphasised by Adam Smith, is that each project should not have to pay a direct financial return to its owner. The dividend of worthwhile public goods is not captured in the form of tolls or other user charges. In transport infrastructure the dividend is in terms of travel time savings, less accident trauma, and less local and global air pollution.

These benefits diffuse through the economy in terms of higher productivity. We make savings in our health care costs, plumbers and electricians can be working instead of sitting in traffic jams, students can spend more time studying. That higher productivity generates more income, and therefore higher taxation revenue to service the public debt that has financed the infrastructure.

That’s basic economics. It’s hard to believe that any politician in the government ministry (or in the shadow ministry) doesn’t understand this.

So long as we allow a puerile and misleading treatment of government debt to dominate our public debate there will be avoidable deaths and crippling injuries on our roads. We will waste our lives sitting in traffic jams, breathing in nitrous oxides from truck exhausts while heating up the planet. We will be denying ourselves the comfort of up-to-date public transport in our cities.

If the Coalition wishes to criticise Labor’s infrastructure policies there are plenty of different angles it can take. But if it raises the ogre of government debt it will be doing itself, and the community, a great disservice.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.