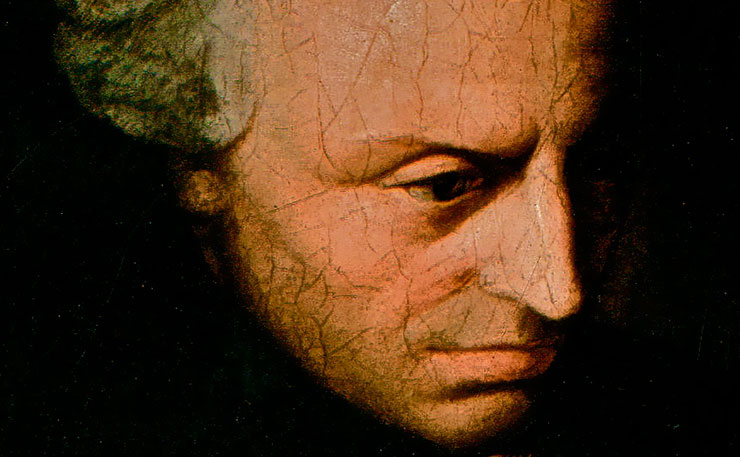

Last week in New Matilda Spencer Jackson wrote an eloquent article outlining the relevance of one of ‘two Kants’ – the cosmopolitan not the racist – for Malcolm Turnbull’s refugee policy. It is a beautifully written and engaging article but it misses the historical and ideological mark. Let me explain.

Immanuel Kant, like all the white, male liberal political philosophers, was racist and sexist. In this, he reflected his times rather than an inherent character flaw. Certainly we expect more of such a canonical figure of the Enlightenment (and a rare few of his peers such as Marquis de Condorcet, or Theodore Gottlieb von Hippel rose to this challenge), but we cannot apply contemporary ideals (‘liberal’ or otherwise) to historically situated thinkers of over two centuries ago.

Secondly, the Liberal Party is only tangentially connected to ‘liberalism’ in its classical form. This is why we have the vernacular distinction between ‘small l’ and ‘big l’ liberal. The Liberal party is philosophically complex because it is both conservative and liberal.

It stands for tradition and, in its populist variants, a parochial nationalism that John Howard and Tony Abbott exploited with brutal, indeed evil, consequences (think Tampa). This conservatism is why the Liberals have been aligned with overtly racist parties like One Nation, and, even under Turnbull, continue with an inhumane asylum seeker policy.

On the other hand, the Liberal party is also connected to free-market capitalism and laissez faire economics, which derives from the liberal political-philosophical tradition. There is a synergy between the ideas of John Locke and Adam Smith; both presuppose a rational, individual acting in his self-interest (and it was his not hers at this stage). At its best this is the philosophical foundation for human rights; at its worst, it justifies the destruction of the welfare state.

So, the Liberal Party — like the Republican Party in the US — is a curious amalgam of culturally conservative, economically liberal and, among the ‘small l’ Liberals (only), politically progressive ideas connected to the Enlightenment such as liberty and equality (although these ideals are often undermined by their own policies).

Under critical scrutiny this combination often collapses and what we find is big l Liberals tend to fall into one or the other camp (liberal or conservative) because they can’t sustain the cognitive dissonance that comes with holding such ideologically disparate positions.

In its pure form, then, the ‘liberal’ in ‘Liberal Party’ is a misnomer. A true ‘liberal’ (in the small ‘l’ sense of this word) looks much more like a Greens candidate: socially progressive not conservative, egalitarian and supportive of a socially mediated form of capitalism underscored by a high functioning welfare state.

They are deeply opposed to government surveillance and the gradual erosion of civil liberties that has, in fact, occurred under the ‘Liberals’.

Malcolm Turnbull is a curious fish because he is beyond the standard political taxonomy of ‘left’ and ‘right’, ‘liberal’ and ‘conservative’. He blends the two in ways that confound those on both sides of politics and, just as paradoxically, appeals to voters across the political spectrum.

As evidence in this regard, he is preferred Prime Minister by those who vote Liberal, Labor and Greens.

Many on the left and in the centre were relieved, even over-joyed, by the deposing of Abbott. He was an arch-conservative; his policies on asylum seekers, climate change, women, Indigenous Australians, same-sex marriage and education were widely out of step with the community.

Into this gap the more moderate Turnbull has stepped amid cheers, sighs, grumbles, and a few sneers.

However, to get to this point, he has made deals with the conservative side of his party – the same side he eyeballed down over his earlier emissions trading scheme in 2008 – and made a series of political compromises, including voting for things he is ideologically opposed to or against those he ideologically supports (or so we think).

And thus now he is caught in a well-documented conundrum: he’s popular for being a ‘small l’ liberal known for his convictions but he’s the leader of a party that are by and large culturally conservative – a party that, in Peter Lewis’s terms, ‘stalled the momentum on same-sex marriage, is opposed to a republic and is dominated by individuals who deny the existence of climate change’.

To this we may add, a party that prior to his own appointment of five women to the front bench declared that only Julie Bishop passed the ‘merit’ test. And Turnbull has yet to address the only issue that will address gender imbalance: quotas. Another issue the conservatives will not countenance. Again he is stuck in the liberal-conservative nexus.

The closer one gets to power the more compromises there are. ‘True liberals’ are incorrigible idealists and politics is, at its core, pragmatic. Machiavelli might be more useful for Turnbull than Kant (Locke, Rousseau, or Wollstonecraft) because politics is the art of the possible, not the ideal.

This is not to say we don’t hold Turnbull to account; we want him to exercise his ideological commitment to ‘small l’ liberalism; we want him to act on climate change, domestic violence, refugees, education, communication, the republic – and not just with words, but with actions and funding.

The irony is that to do so he has to bite his tongue and be the proverbial ‘team player’ in a team of ‘Liberal conservatives’ – a wonderful oxymoron capturing his very dilemma!

So, there are not only ‘two Kants’ (cosmopolitan and racist) but also two ‘Liberals’ (progressive and conservative) and two Turnbulls (idealist and pragmatist).

We are yet to see which side will prevail.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.