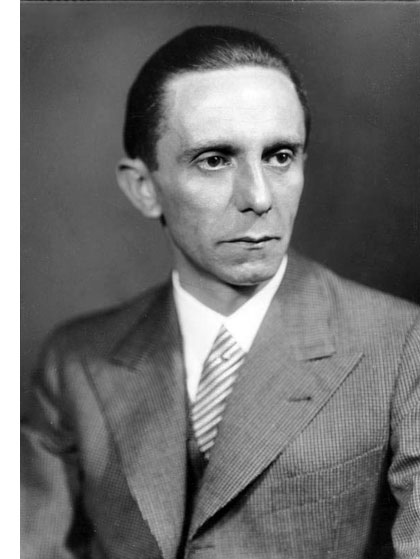

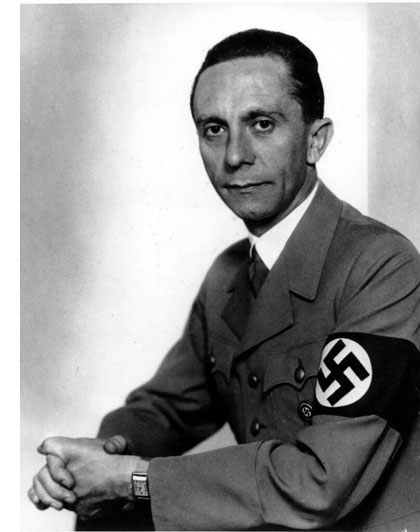

Peter Longerich is one of the world’s leading scholars on the Nazi Holocaust. He has written important studies of the Holocaust, Heinrich Himmler, and in May this year, his lengthy study of Goebbels was published in an English translation.

The scholarly literature on the Holocaust is already vast, so what contribution does this one make? I make no claims to having mastered the scholarly literature. At this point in time, there have not been many reviews of the book, and those I’ve seen have not been written by academic specialists.

I have little doubt that scholarly discussion of the book will shed further light on its achievements and shortcomings. I will review some of what it shows, and then briefly comment analytically on the book. I would like to stress that critical analysis of the book is intended to be tentative, and particularly open to revision in light of better-informed analysis.

So, what do we learn about Goebbels from the book? I intend to just review a few of the book’s threads. Firstly, the nature of some of Goebbel’s propaganda before the Nazis seized power. Secondly, a brief discussion of Nazi propaganda under the guidance of Goebbels. Thirdly, a discussion of Goebbel’s propaganda and role in relation to the Jews. Fourthly, a review of Goebbel’s war propaganda.

Goebbels before the Third Reich

In what Goebbels identified as the “time of struggle”, his propaganda was different to what it later became. Longerich notes that during the early years, Goebbels “would write ironically, bitingly, casually and flippantly.” In power, “his style was serious, statesmanlike, even pompous, meant to indicate that he was viewing current affairs from a certain distance, from a higher vantage point.”

Goebbels was less impressed than Hitler was “by the propaganda put out by the worker’s movement” and “by British propaganda during the Great War”. Goebbels “took his cue from the model of commercial advertising”.

For Goebbels, “commercial advertising was overtly cited as the model to follow. Whether it was a matter of simplification, constant repetition of memorable slogans, or concentration of propaganda material in regular campaigns, the principles of mass advertising could easily be applied to political propaganda.”

His arguments were always accessible to a broad audience. He was a skilled orator, and carefully practiced his various hand gestures. He “enjoyed writing in the vein of a metropolitan tabloid journalist”. In the 1932 election campaign, Goebbels tried to promote a cult of the fuhrer, which wasn’t particularly successful.

Goebbel’s paper Der Angriff had the slogan “For the oppressed! Against the exploiters!” It was driven by, “even by National Socialist standards – strikingly vulgar anti-Semitism.” Besides endorsing the claim of Jewish ritual murder, Goebbels launched a very long and bitter campaign against the Deputy Police Commissioner, Bernhard Weiss.

Deciding that he had a secret Jewish name, Goebbels constantly referred to him as “Isidor”. In 1927 and 1928, only one issue of Der Angriff didn’t personally attack “Isidor”.

Most editions of Der Angriff also attacked Weiss, and Goebbels also published two books on him. Weiss’s appearance was described as “typically Jewish”, and he was characterised as underhanded and cowardly. Many Germans were angry, bitter, and alienated from the political system, and Goebbels tried to channel this anger in an anti-Semitic direction.

Goebbels proclaimed that “we are fighting the system. We don’t speak like the bourgeois parties of the corruption in Berlin or the Bolshevism of Berlin City Hall. No! All we say is Isidor Weiss! That’s enough!”

As Deputy Commissioner, Weiss was in a position to fight back, and there were various laws he could use to challenge Goebbel’s vicious attacks. Goebbels battled constant court cases – including attempts to prevent him from using the name “Isidor”. These drew further attention to Goebbel’s attack, but had little effect in hindering the flood of attacks.

Der Angriff would then mockingly publish respectful references to Mr Weiss, or adopt his full title, and readers would get the sarcasm and mockery.

In one week, Goebbels had four court battles on his hands. Goebbels finally complained that it was starting to wear him down. Yet at other times, Goebbels cheerily welcomed court battles as positive developments.

He adopted a policy of creating provocations to gain attention, and was able to avoid any lengthy stretch of imprisonment, despite battling charges of treason, inciting violence against Jews, defamation and so on.

Nazi propaganda in the Third Reich

As Minister of Propaganda, Goebbels didn’t just take responsibility for his own speeches and writings, but also controlled to varying degrees other areas of German media, such as film and radio.

Goebbels regularly briefed the German news media on his expectations, and in later years explicitly set the line that the media was to follow. The results tended not to impress him.

In the early years, he complained that the media was either “anarchic, destroying and undermining everything”, or “tame as a lapdog”. It needed to find a “golden mean”.

This would be an “independent, decent, well-intentioned critique of individual measures mixed with good, positive advice!” I suppose this would be something like a critique that assumed the Nazi government’s good faith, and gave critical feedback on individual issues, and how the Nazis could better achieve their aims.

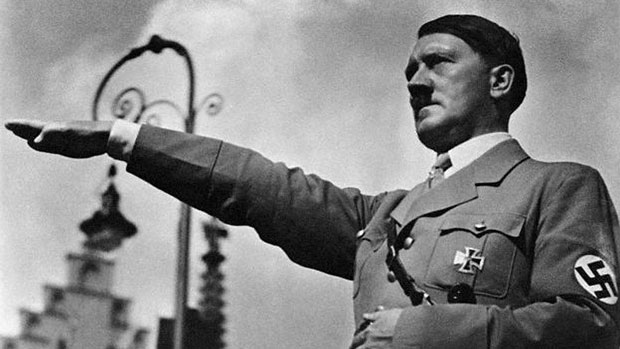

Hitler was unimpressed by the Nazi Party media, which he thought was too uniform; even worse than the bourgeois press. Goebbels wasn’t quite able to institutionalise the kind of lovingly independent media he hoped for. After claiming he wanted well-intentioned critiques, he soon waged an “all-out campaign against critical voices.” He explained that, “When it comes to things that affect the national existence of a people and must therefore be solved by the government, the job of the press is just to take note. Discussion changes nothing, in any case.”

His effect on films was dire, as Goebbels and Hitler both privately conceded. Goebbels took charge of films. He conceded in the pre-war years that “Our films are just very bad”. In December 1943, he admitted that “the current standard of films is beneath contempt.”

Goebbels was determined to keep films under his political control, and the result was that entertainment films were banal, and propaganda films were nationalistic clichés.

At the start of the war, Hitler complained there weren’t enough propaganda films, so Goebbels saw to it that vicious anti-Semitic movies were produced.

In early 1941, Goebbels changed film policy, so that films would be 80 per cent light entertainment, 20 per cent propaganda. “During this period of extreme tension film and radio must enable the people to relax”, Goebbels explained.

During the Nazi era, the one triumph of Nazi film-propaganda was Leni Riefenstahl’s work. Goebbels didn’t particularly like her, recording in his diary: “I chew Riefenstahl out. Her behaviour is impossible. A hysterical woman. She’s just not a man!”

Goebbels and the Jews

Longerich shows at length Goebbel’s long career of Jew hatred, and his key role in pushing more radical measures against Jews throughout the Third Reich.

During the Weimar years, Goebbels was isolated in the Nazi Party, and only had the favour of Hitler, to whom he consistently showed utter devotion. Goebbels tried to curry favour with the SA brownshirts, who he depended on for distributing his propaganda by supporting and enabling their anti-Semitic thuggery.

Longerich observes that in power, Goebbels “took every opportunity in conversation with Hitler to secure his agreement to ‘proceed more radically on the Jewish question,’ and he was determined to ‘sort things out’ in Berlin before too long.

It seemed to him that intensifying attacks on Jews was the best way of diverting attention from the critical political situation at home.”

In 1938, “as in the waves of Jewish persecution of 1933 and 1935, Joseph Goebbels played a leading role.”

In April, he started harassing Jews in Berlin. He announced that “What I’m doing is trying to incite you. Against any kind of sentimentality. The watchword is not the law but harassment. The Jews have got to get out of Berlin.”

Goebbel’s central role in Kristallnacht has long been well-established. Longerich argues that “Goebbels’s objective now was to demonstrate the complicity of the German ‘Volk’ – so obviously lukewarm about the prospects of war a few weeks earlier – in a barbaric, and allegedly collective, action against German Jews, thus making a public display of the solidarity and ideological radicalism of the ‘national community’.”

He then ordered German media to “prepare a big anti-Semitic drive.”

German intelligence indicated the population mostly opposed the 1938 pogrom, and so he hoped to change some minds. Goebbels was concerned that “the upper classes, in particular the intellectuals, don’t understand our Jewish policy, and some of them support the Jews.”

When they also opposed the Jewish star, his initiative in 1941, he complained that “The German educated classes are filthy swine”.

As cynical as much of his propaganda was, Goebbels was a true believer when it came to anti-Semitism. When he visited a ghetto in Vilnius, he privately wrote that, “The Jews are lice that live on civilised humanity. They must somehow be exterminated, otherwise they will keep on tormenting and oppressing us.” Publicly, he was no less vicious.

Goebbels “was determined to play a pioneering role in the radicalisation of Jewish policy during the war as well.” He led the campaign to deport Jews from Berlin, which began in October 1941. As 20,000 Jews were deported, he ordered the press not to comment, before ordering a new round of intensified anti-Semitic propaganda on October 26.

Longerich notes that knowledge of deportations was “widespread among the German population, [and]produced generally negative reactions”.

In January 1939, Hitler issued his notorious “prophecy”: that if the world’s Jews plunged the world into a world war, the result wouldn’t be Jewish victory, but the annihilation of Jews in Europe.

On October 27, the Voljischer Beobachter ran an article with the headline “They Dug Their Own Grave! Jewish Warmongers Sealed Jewry’s Fate”. Goebbels instructed them to reprint the prophecy, and added, “What the Fuhrer announced prophetically then has now become reality. The war of revenge against Germany stirred up by the Jews has now turned on the Jews themselves. The Jews must follow the path that they prepared for themselves.”

In November 1941, Goebbels wrote an article titled “The Jews are to Blame!” Referring to the prophecy, “We are now experiencing the realisation of that prophecy and the Jews are experiencing a fate which, while hard, is more than deserved. Sympathy with them or regret about it are completely inappropriate.” He observed that “World Jewry” was now suffering “a gradual process of annihilation”.

In December, Hitler spoke with Goebbels, and Goebbels recorded the discussion in his diary. He noted that the prophecy wasn’t “empty words. The world war has happened. The annihilation of Jewry must be the inevitable consequence.”

Goebbels observed in his diary on March 27, 1942 the deportations then underway: “A fairly barbaric procedure, not to be described in any detail, is being used here, and not much is left of the Jews themselves. In general it can probably be established that 60 per cent of them will have to be liquidated, while only 40 per cent can be put to work.”

Goebbels tried to rationalise it:

“A judgment is being carried out on the Jews that is barbaric but thoroughly deserved. The prophecy that the Fuhrer gave them along the way for bringing about a new world war is beginning to come true in the most terrible fashion.

There must be no sentimentality about these matters. If we didn’t ward them off the Jews would annihilate us.… No other government and no other regime could produce the strength to solve this question generally. Here too the Fuhrer is the unswerving champion and advocate of a radical solution that the situation requires and therefore appears unavoidable.”

Longerich argues that in 1942, Hitler and other leading Nazis “made repeated public statements about the extermination and annihilation of the Jews, thereby sending clear signals about the fate of the people who were being deported to the extermination camps.”

However, “In general… during 1942 propaganda responded to the ‘final solution’ with silence, a silence that… was eloquent and uncanny”.

When Himmler gave his notorious Posen speech in October 1943, Goebbels recorded in his diary his impressions of the “completely unvarnished and frank picture” presented by Himmler. Himmler “advocates the most radical and toughest solution, namely to exterminate the Jews, the whole lot of them. That is certainly a consistent, albeit brutal solution. For we must take on the responsibility for ensuring that this issue is resolved in our time.”

Goebbels later recorded a discussion with Hitler, whose ambitions to destroy the Jews were not limited to Europe alone. The “Fuhrer emphasised, the Jews in Britain and America are still going to have to face what the Jews in Germany have already been through.”

In April, Goebbels proudly recorded in his diary that, “We shall stoke up anti-Semitic propaganda to such an extent that, as in the ‘time of struggle’ [ie. pre-1933], the word ‘Jew’ will once again have the devastating impact that it should have.”

The German press responded to the massacre at Katyn by the Soviets by carrying out “what was probably the most vigorous anti-Semitic campaign since the start of the regime”. The “whole of the press had adopted the slogan of ‘Jewish mass murder’”.

Still, Longerich notes that Goebbels complained that the press was carrying out anti-Jewish propaganda “by the book” and not “engendering ‘any fury or hatred’ because they ‘did not share these feelings themselves.’”

The general theme was that “Jews must be destroyed not to be destroyed by them.” This was found “in numerous variations in the German press”.

Goebbels announced again in May that “this war is a racial war. It was begun by Jewry, and its purpose and the plan behind it are nothing less than the destruction of and the extermination of our people.”

Invoking the prophecy again, he wrote that at the time “world Jewry simply laughed [it]off… they’re certainly not laughing now… When they devised the plan for the total destruction of the German people, they were signing their own death warrant.”

Goebbels and war

As may be expected, Goebbels propaganda about the war was not entirely accurate. The Nazis claimed the war was started in response to provocations by the Poles. The SS faked the required border incidents.

Goebbels disseminated stories of Polish atrocities to drum up war fever, exaggerating German dead by a factor of 10. Longerich records that Hitler “proclaimed his supposed love of peace”, as he plunged the world into war. He offered peace to London and Paris after conquering Poland, claiming that if they accepted, “order would soon be restored in Europe. If they don’t, then it is clear where war-guilt will lie, and the battle begins.”

When the Allies bombed Germany, Goebbels issued “instructions for propaganda to make more of the attacks on Berlin: ‘Make a huge thing of it in order to provide us with moral alibis for our massive raids on London.’” German newspapers thus “carried pictures of and reports on the destruction of civilian targets”. In general, Goebbels opposed the German media adopting too optimistic an account of the progress of the war, for fear that this could lead to dashed expectations, which would be counterproductive in maintaining morale.

Coming up with a propaganda line for invading the USSR after signing the Non-Aggression Pact required more creativity. To prepare for it, Goebbels tried to hint at an impending invasion of Britain. At first, the reasons he gave for war were that the war was unavoidable, they couldn’t invade Britain whilst Russia was a “potential enemy”, and, for person-to-person propaganda, it would be admitted that the invasion would provide enormous resources to the Reich.

By July, however, he adopted a new propaganda line on instructions from Hitler: the war was a preventive action, because Stalin was about to invade Germany.

The anti-Soviet campaign quickly transmuted into anti-Semitism. Goebbels announced at a ministerial briefing that “the Jews are to blame” was to be the “main theme of the German press.”

Hitler ordered that propaganda draw on the “alleged symbiosis between Bolshevism and the Jews”, and “western capitalism and the governments in London and Washington were puppets of the Jewish world conspiracy.”

When the Allies accused the Nazis of mass murder of Jews, Goebbels recorded in his diary the dilemma this caused him in December 1942.

He observed, “We can’t respond to these things. If the Jews say that we’ve shot 2.5 million Jews in Poland or deported them to the east, naturally we can’t say that it was actually only 2.3 million. So we’re not in a position to get involved in a dispute, at least not in front of world opinion.”

As these reports were becoming “increasingly extensive”, and there wasn’t “much evidence with which to counter” these claims, Goebbels decided a different response was in order. He gave instructions to “start an atrocity propaganda campaign ourselves and report with the greatest possible emphasis on English atrocities in India, in the Near East, in Iran, Egypt etc”.

He wanted “big coverage” of enemy atrocities, and new ones found every day.

Longerich notes that “the effect of the anti-Semitic campaign on the population was highly ambivalent, as is clear from the surviving reports on the public mood. Apart from positive reactions it also produced irritation and opposition.”

There was German “astonishment and unease” at accusations of enemy atrocities, given what was known about what the Nazis had done.

Longerich’s Goebbels

In short, the picture that emerges is of a vicious anti-Semite, who knew what was being done to the Jews, and responded by regularly escalating anti-Semitic propaganda, and blaming them for the extermination the Nazis were inflicting on them.

For personal reasons, it is hard to write dispassionately about Goebbels. It is no less pleasant reading such an enormous book on the subject. Yet it is important not just to remember the past, but to try to understand it.

As a study of Joseph Goebbels, the chief of Nazi propaganda, it is a singular achievement, in that it is based on a vast reading and critical interrogation of Goebbel’s diaries.

These diaries are identified by Longerich as a useful resource in studying the Third Reich, and were also mined extensively for Ian Kershaw’s magnificent two-volume biography of Hitler.

Yet though the two books have been compared in reviews, I think there are significant differences between the two. Longerich wrote a review essay of Kershaw’s biography, noting that Kershaw attempted a broader, sweeping history of the Third Reich, and that his study “often reads like a general history of National Socialism”, where “the author is not always entirely successful in keeping the focus on his main protagonist.”

Longerich’s study, on the other hand, focuses entirely on Goebbels, for over 700 grim pages of text, with almost two hundred pages of bibliography and endnotes.

The result is an achievement in understanding Goebbels as he was, but not necessarily for situating Goebbels in the Third Reich. Besides lacking Kershaw’s gracious writing style – which is possibly a result of translation from German – Longerich makes little effort to explain events within their broader socio-political context, nor to explain events as they progressed to lay readers.

Thus, Longerich gets to 1930 without even mentioning in passing the Great Depression. The Night of Long Knives is briefly noted, without reference to its name, and limited explanation of what actually happened. Likewise for the Hess Affair, where Longerich also doesn’t even identify Hess’s first name, or his title.

Longerich observes the Nazi vote increasing to over 36 per cent, without any attempt to account for how the Nazi vote rose so steeply from less than 3 per cent a few years earlier.

The book is intended for well-informed readers, interested in a close study of Goebbels. It is not a general history for lay-people.

Longerich offers a brief evaluation of Goebbel’s propaganda during election campaigns before the Nazi seizure of power – he mostly dismisses the effectiveness of Goebbels as a propagandist at this time – but doesn’t try to seriously evaluate the role of Nazi propaganda in garnering greater support for the Nazis, as opposed to other factors.

Though there is some – I would suggest limited – discussion of Goebbel’s propaganda during these early years, Longerich has little interest in how that propaganda was received.

I personally suspect that Longerich underplays the receptivity of Germans to Goebbels propaganda through much of the book, but will leave that to historians to analyse.

The book is overwhelmingly a top-down study, relying overwhelmingly on primary sources within the Nazi regime, particularly the diary of Goebbels.

Though the result is a scholarly achievement, and an informative study of the life of Goebbels, I am sceptical of claims that it is the definitive study.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.