In 50 years of texts which analyse public policies, the word cruelty never appears in an index. Yet the desire to inflict pain and distress on other human beings has become a driving force in the policies of governments and in the practices of those who oppose them.

An arbitrary record of cruelties may provoke charges that some practices are far worse than others, or that significant acts – a cataclysmic genocide, inhumanities in a civil war – have been left out. The point is not these omissions but that cruelties have become a stock in trade in public commentary and in policies.

An Inventory of Cruelties

The boastful, ‘We always know everything’ diatribes of Australia’s radio shock jocks – remember the Alan Jones’ claim that former Prime Minister Julia Gillard’s father died of shame – flourish in a culture which says that deriding and demonizing is clever. It is not. It is cruel. It takes massive steps away from any sense of civility.

In contravention of international laws and in degrading conditions, Australia detains asylum seekers on remote Manus Island and Nauru and even pays people smugglers to take people seeking freedom back to Indonesia.

Adrift in the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, then imprisoned in camps in northern Thailand and Malaysia, thousands of stateless Rohingya refugees are treated with appalling cruelty. On SBS News, journalist Sara Abo quoted a Rohingya refugee, Habib Habiburahman, “We have no security, no protection at all. We feel like, worse than animal. So we always live in fear.”

In Saudi Arabia public flogging, amputation and executions are taken for granted by a government which enjoys being a significant partner in a western alliance. They have shown breathtaking cruelty towards the blogger and creator of the website ‘Free Saudi Liberals’, Raif Badawi. Charged with insulting Islam and with apostasy, he was sentenced to one thousand lashes and ten years in prison. He has been flogged fifty times and waits for 950 more lashes and continued imprisonment.

In certain parts of the world competition persists for the first prize for absolute evil. The execution on April 29th of the two Australians Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran, along with six others, illustrated why a government needed to show how macho it was in order to appease those who thought that capital punishment had any deterrent value.

Chan and Sukumaran were executed despite spending 10 years on death row, despite being recognized as having contributed significantly to the rehabilitation of other inmates.

In Gaza, Hamas’ rule includes the arbitrary and summary execution of individuals perceived as collaborating with the Israelis. In a region concerned with violence as a means of government, some human lives are regarded as of little value and cruelty appears to be taken for granted.

Human rights abuses committed by successive Israeli governments against Palestinians have included the siege of Gaza, repeated invasions of that narrow strip and the slaughter of thousands of Gazans, the vast majority of them non-combatants, women and children.

Israel’s illegal use of administrative detention as collective punishment persists as a cruelty seldom challenged by the international community. In April 2015, as part of the Israeli government’s response to the Palestinian Authority’s recognition of the International Criminal Court of Justice, Khalida Jarrar and 16 other members of the Palestinian Legislative Council were imprisoned without trial, without knowing when they might be released.

The organization ‘Defence For Children International’, reports that around 500 – 700 Palestinian children are arrested, detained and prosecuted in the Israeli military court system each year, the majority charged with throwing stones. Three out of every four experience violence during arrest, transfer or interrogation.

The Obama Administration deploys drones to kill almost anyone, the Assad regime uses chemical weapons and barrel bombs, atrocities which seem to have been surpassed by the bestialities of Islamic State forces. Fanatical individuals have decapitated prisoners, dished out similar treatment to people accused of sorcery and have executed untold numbers of men and women because they represented the wrong religion.

Explanations and Justifications

How is such cruelty justified? Why do allegedly civil liberty respecting governments turn a blind eye to such abominations?

An easy response is to say that it’s in human nature to be violent and cruel. This fatalistic argument implies that nothing can be done about the behaviour of bullies, whether Assad in Syria, Netanyahu in Israel, the Rohingya-hating Buddhist monks in Myanmar or the mask-like Australian Immigration Minister Peter Dutton.

A caveat to the ‘It’s in human nature’ argument, is to say that cruelty is a tradition passed down over centuries by male dominated tribal customs. Under those traditions, women can be demeaned, infidels punished and a barbaric status quo maintained. In such cultures the swagger of dominating leaders continues, the oppressed may accept their oppression because they are confronted with the claims cruelty is law.

Forget about human nature and concentrate instead on the political culture in democracies, such as Australia’s, which claims to promote mateship and to support human rights. Either the political leaders fool themselves, or they ignore even the cruelties which their policies promote.

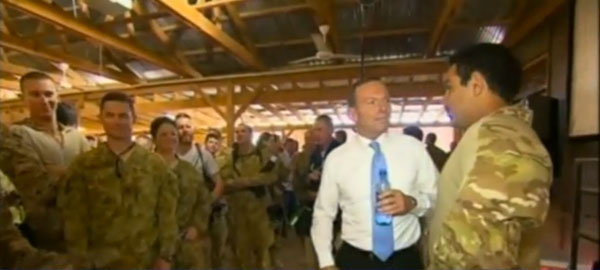

Keeping asylum seekers in limbo on Manus Island or Nauru is defended by the repetitive boast ‘We turned back the boats.’ Under the caption, ‘Turn Back The Brutes’, former Independent MP Tony Windsor wrote in the June 27th edition of The Saturday Paper that the blatantly cruel attitude towards asylum seekers had to end.

There is a more troubling dimension to politicians’ action or inaction. It looks as though a large section of the public believe that indifference to the plight of the vulnerable is acceptable. A letter writer in the Sydney Morning Herald of 19th of April said, ‘Politicians tell me they field more complaints about cruelty to cattle and sheep than to children in inhumane Nauru detention.’

Another part of this political culture is to avoid taking a stand on principle. In answer to questions whether Australian officials had paid crews on asylum seeker boats to turn back to Indonesia, our Prime Minister ducked and weaved, ‘We can’t say yes and we can’t say no.’ Such deception derives from a culture of secrecy promoted by a government which says, ‘Trust us’, ‘Government is complex’, ‘Protecting the country requires secrecy’, ‘You don’t need to know.’

The unwillingness of leaders to offend powerful neighbours or allies is another means of maintaining cruelty. The maintenance of the special relationship between Australia and Indonesia meant that, after the executions of Chan and Sukumaran, the withdrawal of an Ambassador would be no more than a token gesture.

The barbarity of the Saudi Arabian government is facilitated by perceiving that country as an oil rich ally who should not be offended.

As for human rights abuses in China, trade must always trump human rights. Behind the trumpeting of a Free Trade treaty with China is a collusion with human rights abuses. How could it be otherwise ? China is our most significant trading partner.

A Final Diagnosis

Like any serious disease we need to comprehend what causes and sustains it. In the ailing policy-cruelty-body lie five interdependent explanations.

Cruelty is in human nature.

Denial flourishes: in a self-induced psychotic world, politicians can fool themselves and try to fool others.

Given the ‘Are you for or against?’ syndrome, the public is lulled into a false sense of security if they say, ‘We’re so for you that anything goes.’

A pragmatic morality rules, therefore any idea acting on principle is a relic of a bygone age.

Good relationships with powerful allies must be maintained irrespective of their cruelties.

An x-ray of the ailing body politic shows a pattern of fascination with violence, in words, in deeds and in the crafting of policies. Before the condition can be treated, powerful people must acknowledge that it exists, that they practice cruelty or facilitate conditions which allow it to flourish.

* Stuart Rees is the Founder of the Sydney Peace Foundation.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.