Another day, another air disaster, right?

Overnight, Australian news sites began live blogging the details of the latest disaster – the crash of Germanwings Flight 9525, an Airbus A320 which crashed into mountains in France.

All 150 passengers and crew – including two Australians – are reported to have died.

Obviously, it’s a tragic event. But the reality is, commercial aviation today is safer than it’s ever been. But don’t believe me – believe the statistics.

2014 recorded the smallest number of major commercial aviation incidents in more than 50 years. You have to go all the way back to 1957 – when Robert Menzies was Prime Minister – to find a comparable year in terms of total number of fatal incidents.

There were seven (both in 2014 and 1957).

But even though 2014 had the lowest number of fatal commercial incidents on record, in Australia, 2014 saw the highest amount of news reporting of aviation disasters.

That’s due in no small part, obviously, to the mystery surrounding the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, and the downing of Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 over the Ukraine, with 27 Australian passengers on board.

So, we’re now a nation obsessed with aviation disaster. Or at least our news outlets believe we are. It all begs the question: why, as major commercial aviation disasters become less frequent does media reporting of them become more saturated, and more intense?

The answer is obvious: media have to write about something, and no news site in history (at least not yet) has been able to turn a car crash into rolling, 24-hour, live blog news coverage, despite the fact you’re far more likely to die behind the wheel, than jammed in cattle class.

Plane crashes are a bit like terrorism – they make for interesting copy, but they give an over-exaggerated sense of threat. How ironic that media are often the worst offenders when it comes to providing perspective.

So in the interests of that perspective, here are some simple facts and statistics about flying.

Commercial airline crashes in 2015

Around the world, there have been three major air crashes this year. The first was in early February in Taiwan – TransAsia Airways Flight 235, an ATR-72 crashed into the Keelung River, killing 42 of the 58 passengers and crew on board.

The second was earlier this month, when Delta Airlines Flight 1086, a McDonnell Douglas MD-88, overshot the runway at LaGuardia Airport and crashed into a fence. No-one was killed although more than a dozen were injured.

The third, of course, was overnight.

Best and worst years for flying

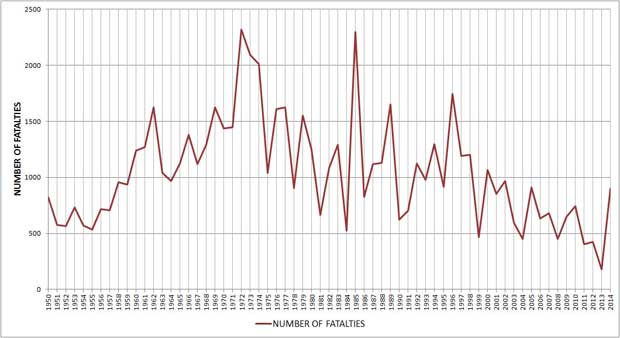

In terms of total numbers of passengers killed, 1972 was the worst year in history.

2013 was the safest year in history (there were less accidents in 2014, but they involved larger numbers of people).

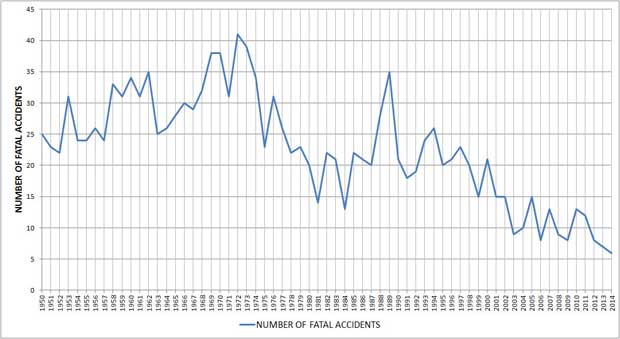

As to the number of fatal crashes (as opposed to numbers of people killed) 1972 was also the worst year ever when there were 41 fatal accidents world-wide.

The best year on record was 2014, when there were six accidents with 19 or more fatalities.

The odds of an error

About half of all fatal accidents on commercial airliners are caused by pilot error. Mechanical failure is next, followed by bad weather and then sabotage.

Landing a plane is the most challenging part of a flight for a pilot, which is why pilot error accounts for the most fatal incidents. But surprisingly, the landing is not the most dangerous part of the flight (more about that shortly).

The staggering odds of dying in a commercial plane crash

If you fly with one of the 39 safest airlines in the world, then on current statistics, you’d need to take almost 20 million flights in your lifetime before, on average, you would be killed. As a rough guide, you’re twice as likely to win Saturday Lotto.

To put it in even more perspective, in order to guarantee your death (statistically speaking), you would need to take about 650 flights a day, every single day of your life, from the day of your birth to the day of your death (at 82.10 years of age, which is the average Australian life expectancy).

A side note though: if you’re planning on testing the theory, don’t fly with one of the big three Australian airlines – Qantas, Virgin and Jetstar have never recorded a single fatality, and thus on current statistics, no matter how often you fly, you’ll never die (at least not from a plane crash… a Deep Vein Thrombosis from the cramped seating is statistically far more likely).

If you’re going to die, when is it most likely to happen?

Contrary to popular opinion, the most dangerous phase of flying is not the landing. It’s actually the take-off.

While about one in three accidents occur during the final approach and landing, they only account for about one in four of the total fatalities.

Conversely, about one in four accidents occur during the take-off and initial climbing phase, but these account for almost one in three of the total fatalities.

In short, you’re more likely to crash during the landing, but you’re more likely to die during the take-off.

The reason why is simple.

The take-off

When a plane is climbing, its nose is in the air and it’s relying on engine power to keep it flying. If it loses that power, the wings will quickly stall – ie. they won’t be generating enough lift to keep the plane flying, let alone climbing. The nose of the plane will drop, and it can become very difficult to control.

The only way the plane can recover is if it gains enough speed to re-generate lift under the wings. And the only way to generate that speed is to shed altitude. This is where it gets tricky, and it’s why the take-off phase is the most dangerous: if you don’t have enough altitude, you’ll never gain sufficient speed to get the plane gliding before you hit the ground.

It’s easier to understand if you think of it like this: throw a paper plane as hard as you can. Initially, it will tend to fly out and upwards (because it’s got a lot of speed, so the wings are generating more lift). Once the paper plane runs out of speed, it will stall in the air, then dive before it levels out and starts gliding.

The landing

By contrast, when you’re coming in to land, the plane is using comparatively much less power – it’s relying on its air speed to keep the wings flying (basically, it’s almost gliding). In calm weather, small aircraft generally complete the final phase of their landing with the engine idling (like a car engine at traffic lights).

So even if a large commercial plane loses its engines on final approach, while you still have a big problem, you have a much better chance of landing than if you’re pointed skywards, trying to take off. And that’s simply because you have altitude and speed, and the plane is already under control. You can rely on the glide speed to bring the plane in safely.

A good landing is basically just a stall

It’s a little known fact that in order to land a plane, a pilot will stall the wings – that is, your airspeed drops so low that the wings no longer create lift, hence you’re no longer flying. Obviously, it’s best to aim to do that a foot or so above the runway.

All students of flying are taught that any landing you walk away from is a good one, and any landing you walk away from and can use the plane again is a great one.

Losing power at high altitude

If a plane completely loses power at high altitude (which is rare), you have a major emergency on your hands. And the size of the emergency depends on where you are. But it’s not an absolute death sentence.

If you’re over land, you have a chance of survival, depending on the terrain beneath you. You can glide around and hope to find a clear spot to land. Obviously, this is much harder for large commercial airliners, given their size.

If the area is heavily wooded, you’re in trouble – trees have the same affect at high speed on a plane as they do on a car.

It’s all about the glide

If you’re high in the sky, and the engines do cut out, you’re incredibly unlikely. The chances of total engine failure in commercial aircraft are very, very low. But if it happens, don’t assume you’re going to die.

The glide ratio of a commercial airliner – that is, the distance it travels versus the altitude it loses – is actually surprisingly impressive.

Commercial airlines like a Boeing 747-200 have glide ratios of around 15:1. That means that for every 1,000 metres of altitude they lose, they’ll travel about 15 kilometres over the ground.

Thus, if a 747-200 is cruising at 10,000 metres (33,000 ft), it can glide about 150 kilometres with no power.

Of course, landing a commercial airliner without power is extremely challenging (it’s called ‘deadsticking’, a reference to the fact that the flight controls are very sluggish). But it has been done successfully before.

The most famous was US Airways Flight 1549, an A320 Airbus which left LaGuardia Airport on January 15, 2009 and lost both engines after striking a flock of Canada Geese during take-off (ironically, bird strikes are one of the great threats to planes, hence why airports have employed all sorts of measures to dissuade birds from hanging about).

The pilot in command, Captain Chesley B. "Sully" Sullenberger, and First Officer Jeffrey B. Skiles, successfully landed the plane without loss of life… into the nearby Hudson River.

It remains the most celebrated emergency landing in commercial aviation history.

* Chris Graham is a frustrated ‘pilot’, having never quite completed his training, which he commenced in 2001.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.