Last week Ben Eltham wrote two articles for New Matilda dealing with the latest escalation of border protection harshness by the Abbott government — the so far stalled attempt to send 153 Sri Lankan asylum seekers directly back to the country they fled from.

The articles were entitled How did we let this terror happen? and Confronting the awful truth about our politics on asylum seekers, fittingly enough because in them Eltham repeated the most common explanation for why politicians have engaged in a race to the bottom on asylum: “Both major parties, and a majority of voters, have been complicit”, and this is because the harsh policies have produced “satisfaction” among “much of the voting public”.

In the second article Eltham pronounces at length on the hard-hearted, xenophobic and outright racist tendencies of the majority of voters, and complains that while “some Labor supporters will inevitably leak to the Greens over the issue… the hard truth remains that many ALP voters applaud tough measures on asylum seekers”.

In case we weren’t clear, Eltham claims that “of course, there’s the racism. When politicians talk about ‘controlling borders’ and the need for an ‘orderly’ immigration process, they are in fact dog-whistling to those who fear the unregulated invasion of teeming Asian masses”.

Eltham writes, “As long as the satisfied and the befuddled outnumber the outraged by a fair margin, it seems clear that there will be little popular will to restore a more liberal and generous system for those seeking refuge on our shores”.

Softening border policy would be electoral madness. Eltham does marginally qualify this by remarking that “it is probably true that harsh policies towards asylum seekers are far from the electoral trump card they are often portrayed”, but regardless “you can hardly point to a deep reservoir of sympathy and popular support for those travelling to Australia by boat”.

In a 2012 article he links to, Eltham referred to the origins of the current mess in the Keating government’s introduction of mandatory detention in 1992, arguing that, “As in our own time, this was a knee-jerk policy prescription designed to appease xenophobic Labor voters in marginal seats”.

The chain of causation is explicit: Politicians respond to the dark passions of the voters and the electoral calculus makes resisting these difficult if not impossible.

Last Thursday Eltham returned to this theme: “The progressives who support asylum seekers remain a small minority. No diatribes about the ‘political classes’ can conceal this fact.”

Eltham is not alone in this assessment. The vast majority of opinion on the issue is that asylum policy is “poll-driven” in the sense that it can swing votes to decide the outcome of federal elections.

For example, when Julia Gillard “lurched Right” on asylum and population in 2010, Josh Gordon wrote in The Age, “It is a red-hot political issue, particularly for ‘Howard battlers’ in marginal electorates”.

Kevin Rudd’s 2013 “PNG Solution” led John Pilger to argue that this “barbarism is considered a vote-winner” and “a crude, often unconscious racism remains an extraordinary current in Australian society and is exploited by [the]political elite”.

At around the same time George Negus opined that asylum policy was about “votes, votes and more votes”.

Perhaps the best-known articulator of this position on the Left is David Marr, who has pursued an analysis of the Australian public as deeply susceptible to manipulation by a panic-mongering political elite, especially on issues of race.

During George Brandis’ recent push to water down sections of the Racial Discrimination Act, Marr even suggested that there were “millions” of potential votes in exploiting racial fears.

The problem with these arguments is that there is no direct evidence for them, only presumptions based on a prior belief about the impact of the issue on voting behaviour.

In fact, the more plausible interpretation of publicly available data is that while most voters disapprove of “unauthorized boat arrivals” and may well be “satisfied” with tough deterrence measures, they don’t dislike asylum seekers anywhere near enough to bother switching their vote on the issue.

That is, despite the hysteria of the Right and Left of the political class, boat people do not have a significant impact in terms of swinging votes and deciding elections.

However, it is clear that many politicos believe the asylum issue is a vote swinger. This was a belief cemented after the 2001 “Tampa” federal election, in which John Howard scored an allegedly improbable victory after his government had been in the opinion poll doghouse for most of the previous two years.

Yet as Peter Browne pointed out in a careful analysis of that year’s opinion polls for Inside Story, the electoral boost from Howard’s belligerence towards the refugee-carrying MV Tampa was less spectacular than is often claimed.

It was also hard to disentangle any “bounce” both from the recovery in the Coalition vote that had been happening for months beforehand, and from the effect of the 9/11 terrorist attacks and Howard’s backing of the US invasion of Afghanistan and the War on Terror.

Even then, by concentrating on health and education issues, Kim Beazley led the ALP back to a 2PP of 49 percent, with the government gaining just two seats on 1998.

The psephologist Peter Brent (Mumble), looking only at Newspoll data, came to a similar conclusion in 2011. In a more recent piece Brent pointed out that before the Tampa’s arrival the Coalition had already recovered to a 2PP of around 48 percent, and that the resultant 3 percent rise by election day was equivalent to its performance in the lead-up to the 2004 and 2007 elections.

In a 2003 article in the Australian Journal of Political Science, Ian McAllister analysed survey data on the 2001 election from the Australian Election Study (AES).

The AES showed that “refugees, asylum seekers” was rated fourth among issues rated by voters as most important in the election, considerably behind “education”, “taxation” and “health, Medicare”.

McAllister concluded that border protection in general probably did have some effect on shifting votes, but that:

Labor lost voters on different aspects of the border protection question, with the Coalition benefiting from those who thought terrorism was important, and the Democrats and Greens from those placing more weight on refugees and asylum-seekers. The Coalition lost voters to Labor mainly on education.

McAllister also argued, “Of the two border protection issues — asylum-seekers and terrorism — terrorism was the more important of the two in shaping the election outcome.

If 11 September had occurred but the Tampa crisis had not, the Coalition would in all probability still have won the election”.

Further, “support for the ‘war on terrorism’ was based mainly on notions of fairness and democracy” as opposed to the racialised concerns many think lie behind support for tough border policies.

The strange disappearance of 9/11 from the “Tampa election” narrative — a narrative that accentuates the alleged racism of the voting public as the key reason for Labor’s defeat — has become a convenient distraction from the real reasons for Labor’s problems in 2001: Its continuing agony at the hollowing out of its social base and its inability to beat a Howard government plagued by deep troubles of its own.

As The Piping Shrike has argued, “The so-called ‘Tampa effect’ was really a way that Labor (and left-wing commentary around it) could re-represent having nothing to say to its supporters to become a problem with the supporters itself”.

The War on Terror gave Howard a temporary reprieve from the Coalition’s own decline, but these benefits had petered out by around 2006 so that Howard was not only watering down his refugee policies, but found manoeuvres like the Haneef affair, the NT intervention and attempts by immigration minister Kevin Andrews to demonise African immigrants falling flat.

It is even harder to make the case that boats have shifted votes or polled voting intentions at times other than 2001. For example, Labor’s introduction of mandatory detention in 1992 had little to do with “appeasing xenophobic voters” as opposed to its frustration at courts protecting asylum seekers’ legal rights, with the Opposition playing politics in the background.

Alternatively, when Rudd took Labor’s asylum policy to its softest configuration in years, there was no collapse in Labor support, but rather the defeat of the Howard government and another two years of stratospheric Labor polling.

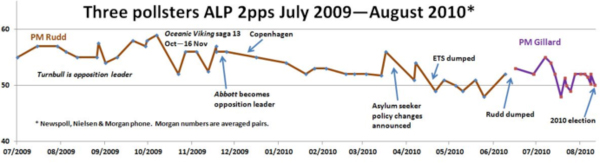

As this graph (below) of Labor’s 2PP from Peter Brent’s blog indicates, not even the Oceanic Viking episode of late 2009 delivered a sustained blow to the government’s standing.

If anything, Rudd’s submission to internal demands to harden asylum policy is more logically explained as the result (not the cause) of the government’s problems following the setback to Rudd’s “great moral challenge” on climate in Copenhagen.

Finally, it was Rudd dropping his ETS that dealt the most damage to the government’s popularity, although much of its primary support went to the most pro-refugee party, the Greens.

Of course, once Gillard took the leadership and “lurched Right” on asylum seekers and population as the geniuses from Sussex St had been demanding, it was of no help as the ALP stumbled towards minority government.

In the lead-up to last year’s election the same paradoxes applied. As I laid out in The Guardian, while Rudd’s “PNG Solution” gave Labor its best ratings on the issue in years, it barely shifted the overall polling which had until then been going well for Rudd.

Perhaps most tellingly, when voters were asked at around the same time for their most three most important election issues, asylum seekers continued to be near the bottom of the list.

This has been the pattern in most polling over the last 15 years, which consistently shows issues like economic management, health, education and unemployment are the at the top of the list of voters’ concerns.

“Stop the boats” may have been one of Abbott’s tedious three-word slogans, but in fact it was downplayed compared with issues of national debt, economic competence and “Labor chaos” in Coalition campaigning.

And since September, Abbott and Morrison’s apparent success in preventing unauthorized arrivals reaching our shores has not protected the government from failing to have a honeymoon, falling behind in the polls within three months of its landslide win, and seeing its support collapse in the lead-up to the Budget.

Voting behavior aside, even the question of how to interpret polls regarding attitudes to asylum seekers can be a vexed one. In a major 2011 study for the federal Parliamentary Library, Murray Goot and Ian Watson concluded regarding social attitude surveys to population, migration and asylum seekers:

First, since 2005, the proportion of respondents saying too many migrants are coming to Australia has increased. Second, while opposition to immigration may be on the increase, levels of opposition in recent years have been lower than those recorded in the first half of the 1990s or in the 1980s. Third, the polls reporting the highest levels of opposition — all conducted online — have framed the questions in ways that appear to encourage responses opposed to immigration.

Further, they noted that the “proportion of respondents wanting drastic action taken about ‘illegal immigration’ is high and growing, but this is partly an artefact of the narrow choices posed by some questions. Less brutal questions sometimes generate less brutal responses”.

An example of how misleading the attitudinal polling results can be was seen around whether processing of asylum seekers should be “onshore” or “offshore”. As Gillard’s obsession with finding an offshore solution reached new heights in September 2011 when her Malaysia Solution was struck down by the High Court, a Nielsen poll showed a clear majority of voters (including Coalition voters) favoured onshore processing, while an Essential poll a few weeks later — using questions around party-identified policies — showed much less support for onshore processing.

Similarly the perception of whether the government is “too tough” or “too soft” on asylum seekers seems to have less to do with its actual policies than with impressions of partisan behaviour.

The reality is that the asylum issue has become the key expression of a panic of the political class at the erosion of its authority.

For Labor hardheads, it is a way to explain their loss of social base, while for Coalition operatives it is about asserting authority through defending “national sovereignty”.

Each side may believe the policy is electorally crucial, but in reality it represents how they project their own degeneration onto voters.

This displacement means they shed crocodile tears over the need to stop “evil people smugglers” and “deaths at sea” when in fact they are using refugees as cannon fodder in partisan games.

To explain the self-serving behaviour of politicians on the basis of popular attitudes is even more upside-down in an era when the disconnect between major party policy and social attitudes on most of the key socioeconomic questions is greater than at any time since regular polling began.

It is politicians’ detachment from society that means they can believe their obsession with asylum seekers is mirrored in the wider community.

They are aided in this delusion by a media (including its left-wing variants) that incessantly peddles the “blame the voters” line, despite the lack of evidence.

Ben Eltham’s articles repeat the linguistic slip of describing the actions of governments and political operators and then deploying the word “we” as if all Australians share equal responsibility for what is going on.

This is especially corrosive because while the political elite’s bipartisan race to the bottom isn’t electorally effective, it can serve to harden social attitudes and inhibit solidarity between Australian residents and asylum seekers, both of whom suffer at the hands of a self-interested political class.

By posing ordinary Australians as the cause of the brutal treatment of asylum seekers, refugee advocates are reduced to making moral exhortations rather than trying to find ways to link ordinary people’s and asylum seekers’ struggles against the politicians on the basis of shared interests.

Worse, like Eltham, they hunt around in vain for a section of the political class with the “courage” or “will” to stand up to brutish voters, much as the Right pines for a strong hand to impose unpopular and unjust economic austerity.

There are dissenters from this approach, for example within the Refugee Action Coalition, but they remain a minority among refugee advocates.

There is also an implicit belief that voters’ self-interest is a bad thing and they should be more “altruistic”, “caring” and “compassionate” towards refugees.

As morally comforting as this may sound, it does nothing to challenge Abbott’s central claim that border control is part of defending a “national sovereignty” that is allegedly in all our interests.

Even refugee supporters as impassioned as Eltham accept there must be some border controls and that national sovereignty is a good thing, and so their argument ends up being about what level of coercion is tolerable in dealing with the asylum “problem”.

The more Abbott and his Labor counterparts deploy nationalist arguments to try to shield themselves from growing popular contempt towards the whole political class, perhaps we would be better off asking whose interests borders actually protect and whose sovereignty we are actually talking about?

It seems to me that — rather than moralizing about the racist masses — it would be much more productive for the Left to start a conversation about how the self-interest of ordinary voters and the self-interest of asylum seekers could be brought together against both sides of our barbaric, degenerate, self-obsessed political class.

But I’m not holding my breath.

Tad Tietze was co-editor (with Guy Rundle and Elizabeth Humphrys) of On Utøya: Anders Breivik, Right Terror, Racism and Europe. He blogs at Left Flank and tweets as @Dr_Tad.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.