I was trying to think of an analogy to the endemic problem of retaliation against whistleblowers, and the need to protect them in order that they make their important disclosures in the public interest.

Then it came to me that it was simpler than I had first thought.

Imagine the playground bully is a bad set of protections and laws, and the whistleblowers, are the kids trying to protect their lunch money — the disclosures.

Earlier, when I was uploading The Whistleblower Protection Rules in G20 Countries: The Next Action Plan report to my social media microphone page, in a triumph of authorship, the only tagline I could think of was: “Lesson learned: G20 still mean to whistleblowers”.

It fits perfectly with the ‘bully’ analogy I wouldn’t inspiringly come up with the following day.

In theory, the legal method of protecting whistleblowers is simple.

Whistleblower has information in the public interest. Whistleblower discloses information. Other people who don’t like this information being revealed are prevented from being mean to Whistleblower. Simultaneously, make it easier to reveal that information through systemic and technological improvement. Corruption ends. Everyone is happy. I am allowed to watch the World Cup, guilt free.

The problem, however, is that not everyone in the G20 has delivered on the promise to defeat the Bully that is bad whistleblower laws, and those that have, have done so half-heartedly.

In fact, in 2010, each of the G20 countries promised serious reform of the laws and rules protecting whistleblowers.

This has partially taken place, as evidenced by new whistleblower laws introduced since 2010 across much of the G20 — Australia, France, India, Italy, the Republic of Korea and the US — and in other parts of the world.

However, in other parts of the world, serious gaps remain.

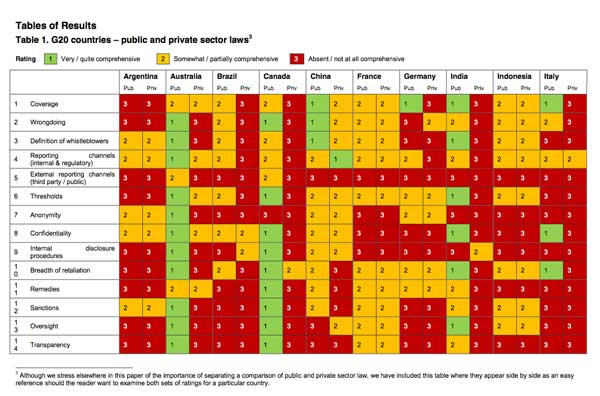

Reading the report, there are lots of coloured tables essentially pointing out where the Bully is strong — the red squares — and where the Bully has been injured or sent to the principal’s office — the green squares.

Each of the rating squares corresponds to a principle — an element necessary to have in a whistleblower protection law.

The tables revealed four main problems in both the public and private sectors.

The first is that most countries lack protections for a whistleblower wishing to disclose information outside their organisation (ie. to the media, NGOs, members of parliament, etc.).

This would be like preventing the bullied child from speaking to someone outside the school, including, for example, his parents.

The second problem is that whistleblowers are not protected when whistleblowing anonymously.

For a whistleblower, this can sometimes be the safest way to make a disclosure — for fear of those who might not want that information revealed taking it out on the messenger.

The laws must recognise the importance of anonymous disclosure, and encourage the development of practical tools — mostly now through secure electronic channels — to allow it. Such recognition will also clarify that disclosing in such a way is still worthy of protection.

For the bullied child, this would mean speaking to a teacher or responsible adult privately — or via a note left under the Principal’s door, not under the watchful eyes of the Bully.

The third problem is that most laws do not require organisations to have whistleblowing procedures.

This is like a school not having a pro-active bullying policy. It is far better to prevent the bullying from happening, through good education, training and robust procedures, than to deal with the aftermath.

Fourth, the tables show that there is lack of transparency and accountability in whether the whistleblower protection laws serve their stated purpose.

In other words, having annual reporting requirements with open reporting about how whistleblowers make disclosures, and how they are treated in particular organisations and so on.

It’s akin to a teacher holding a massive sign emblazoned with ‘nothing to see here’ in front of the Bully poking the Whistleblower in the ribs.

Our report is the first of its kind to compare the performance of whistleblower protection laws in both the public and private sectors.

Interestingly, though perhaps not surprisingly, it demonstrated that protection in the private sector is generally far sparser than in the public sector.

In an age that demands openness and anti-corruption priorities across both the public sector and the private sector, this is unacceptable.

Consider also that the private sector in all G20 countries now performs many functions traditionally performed by government and the public sector — running prisons, private armies, schools and hospitals.

The gap in protection is no longer justifiable — just as a Bully in a public school should be stopped, so should a Bully in a private school.

It is also important to be mindful that a lack of comprehensiveness of whistleblower protection undermines the areas in which countries are performing well.

For example, even if a country has an excellent law ensuring internal whistleblowing within an organisation, if that same country does not allow for that to be done confidentially, or anonymously, then the internal disclosure procedure is good on paper, but of less use in practice.

It is no good leaving open the door to the counsellor’s office if the Bully is waiting outside.

Similarly, where the definition of a Whistleblower is broad — an employee, a contractor, a sub-contractor, the aunt of the favourite butcher of the contractor — this is undermined by large carve outs to the scope of the legislation, usually for military and intelligence agencies.

Protection against the Bully needs to be holistic, and it needs to be re-focused to ensure that those brave enough to come forward can do so in the knowledge that they will be safe.

That’s not too much to ask.

The G20 Anti-Corruption plan is not yet finalised, but will be completed in time for presentation at the November 2014 G20 meeting in Brisbane, Australia.

It is not all doom and gloom; there is evidence of progress in the development of whistleblower protection law.

But it has not yet come far enough.

The Bully must be stopped. The only way to stop him is for G20 countries to continue making that a priority.

Plus, today is ‘fish and chips’ day at the canteen and I need my lunch money.

Simon Wolfe is the lead author of The Whistleblower Protection Rules in G20 Countries: The Next Action Plan report. He is the Head of Research at Blueprint for Free Speech (NGO) and is a Visiting Scholar at The University of Melbourne.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.