The New South Wales government of Mike Baird wants to sell off half of the state’s electricity network.

Baird announced plans yesterday to issue a 99-year lease of 49 per cent of the state’s electricity networks. He will use the money to build new infrastructure in Sydney and New South Wales, including a new harbour crossing, extensions to the WestConnex highway system, and upgrades to Sydney’s commuter rail network. Arts and culture even gets a guernsey, with part of the proceeds of the sale earmarked for upgrades to cultural institutions like the Arts Gallery of New South Wales.

All up, the state hopes to make $20 billion which it can then “recycle” into new initiatives.

The New South Wales government is not alone. The state of Queensland also wants to sell assets to improve its bottom line. Treasurer Tim Nicholls wants to sell ports, electricity companies and even a water pipeline, hoping to raise $33 billion to pay down debt and invest in new infrastructure.

In case you didn’t realise, privatisation is back on the agenda. Indeed, you could be forgiven for wondering if it ever went away. For conservatives, but also for opportunistic Labor governments, privatisation has long enjoyed a special prominence in the policymaker’s bag of tricks.

Governments love privatisations because they solve a short-term fiscal problem. A budget in the red can suddenly be transformed by the sale of a big asset, giving the government of the day a big new fund to build infrastructure, bribe voters and distribute fiscal largesse.

It doesn’t matter that privatisation has a decidedly mixed record. Some privatisations make precious little money. Some make oodles of money for the government, but create big long-term problems down the track.

The sale of Telstra is perhaps the best example at the federal level. The Howard Government reaped a huge financial windfall from selling the telco. It also created a 900-pound gorilla in Australia’s telecommunications industry, one that has used its market power and vast trove of assets to stifle competition and frustrate the development of Australian broadband. The whole reason Labor decided to build the National Broadband Network was to create a structural separation in the Australian industry — so that Telstra could no longer use its power to monster smaller and nimbler competitors.

When governments get their sums wrong, privatisations can end up stealing huge sums of money from the public purse. Governments sometimes sell too quickly at knock-down prices. The result simply transfers public assets to the private sector at a big discount. The new owners of those assets then set about making money from then, often by hiking prices. Inevitably, the shareholders benefit, while the public loses out.

The problems often arise where governments sell monopolies or oligopolies into barely competitive markets. In an industry where one or two firms dominate, competition can dwindle and customers can be gouged. Where regulations are lax, or where regulators are more concerned with the interests of industry than of consumers, the result can be rapid price rises.

Can you think of an industry which is oligopolistic, poorly regulated, opaque, and in which prices are rising rapidly? That sounds a bit like … electricity.

As we’ve reported on extensively here at New Matilda, Australia’s electricity “market” is barely a market at all. While demand keeps falling, prices keep rising. The reasons are many and complex, but the structure of the National Electricity Market is a key factor. The current rules allow electricity networks to pass on all their infrastructure costs to consumers. As a result, networks have a big incentive to keep upgrading their infrastructure. No less an authority than Ross Garnaut has called it “gold-plating.”

Believe it or not, state governments like New South Wales and Queensland are a big part of the problem. Because they both own and regulate the networks, they’ve been only too happy to gold-plate the system, knowing that voters hate black outs, and that the extra infrastructure will flow straight in state treasury coffers.

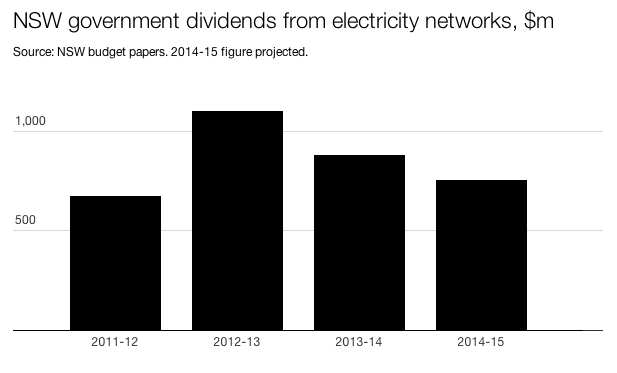

The graph above shows just how much money New South Wales makes off its electricity networks. Over the four years from 2012-15, the state will average $849 million annually from dividends paid by state-owned electricity networks. You can see why the private sector would consider this an attractive proposition.

If it sells off those assets, the New South Wales government will no longer have that money to invest in roads schools and hospitals. Yes, it will have money now, but it will have less income down the track. And the government is not, on the whole, planning to use that money to invest in income-generating assets. It wants to use the money for infrastructure. It’s hard to see how the taxpayers of New South Wales will come out ahead.

An analysis of electricity privatisation in Australia by respected University of Queensland economist John Quiggin found that electricity privatisation in this country has been a big win for the private sector, and a big loss to the general public.

In a report commissioned by the Electrical Trades Union — a body understandably opposed to privatisation — Quiggin, an international expert in privatisation, points out that the promises of privatisation were never kept.

“Privatisation, corporatisation and the creation of electricity markets were supposed to give consumers lower prices and more choice, to promote efficiency and reliability in the electricity network, and to drive better investment decisions for new generation and improved transmission and distribution networks,” he writes.

Quiggin concludes that “none of these promises have been delivered.”

In fact, prices rose dramatically. The reasons were often entirely prosaic: private sector companies wanted to make money, and government regulators were only too happy to let them. When new infrastructure had to be built, electricity networks made sure it was consumers who footed the bill.

As Richard Cooke points out in a fine recent essay for The Monthly, privatisation is an issue that leaves the public and the political classes completely at odds. Poll after poll finds voters are opposed to privatisation; in Queensland, for instance, many think the Bligh Labor Government’s decision to privatise state assets marked the beginning of the end of its long reign. Voters also generally oppose selling off Medibank Private, Australia Post, and the Snowy Hydro Scheme. Few politicians seem to care. “Australians of all political affiliations loathe privatisation,” he argues. “Both major parties propose it continually.”

Exactly this has happened in New South Wales. Barry O’Farrell went to the 2011 election telling New South Wales voters he wouldn’t privatise the electricity network. He was still saying the same thing earlier this year.

But O’Farrell is history. Mike Baird is the Premier now, and he wants to sell off the family silver, despite having absolutely no mandate to do so (a point he seems to have admitted, judging by this tweet).

Why does Baird want to sell off an income-generating asset? The answer appears to be the usual mixture of short-term thinking and fear of budget deficits. State governments of all political persuasions are struggling with anaemic revenue streams and ever-increasing obligations for expensive services. Go-ahead premiers like Campbell Newman and Mike Baird also want to build infrastructure. But the constant, gnawing fear of public debt and budget deficits puts a brake on such ambitions.

Privatisation provides a way out of the impasse. Selling off assets allows state premiers to pose in high-vis and hard hats without borrowing — indeed, while posing as fiscal hard heads. If consumers are stuck with higher power bills down the track, conservatives can blame the carbon tax, or even more bizarrely, solar panels.

As for the foregone revenue? That’s a problem for a future government to sort out.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.