Among the 53 nations that comprise the Commonwealth, AIDS is attributed as the cause of death of 1.2 million people every year. When health statistics from the Commonwealth nations are compiled it emerges as the leading cause of death.

Though the Commonwealth seems superfluous and antiquated, it could be a powerful organisation through which to promote LGBTI rights.

Closely related to this statistic is the fact that more than half of the countries that criminalise homosexuality are member states. On the opposite end of that scale there are only three member states (Canada, New Zealand and the UK) that consider hate crimes based on sexuality to be constitutive of aggravating circumstances under law.

Earlier this week the Australian Senate passed a motion calling on Parliament to acknowledge LGBTI rights, particularly within Commonwealth nations. Moved by the Parliamentary Friendship Group for LGBTI Australians, it was passed unanimously.

Coverage of anti-homosexuality legislation — for example in Uganda — often focuses on the influence of American evangelicals but ignores the broader culture of criminalisation in the Commonwealth. Ninety per cent of member states criminalise sex between men. From Papua New Guinea to Belize, India to Kiribati; Commonwealth states account for 43 of the 81 states that criminalise homosexuality globally.

It ought to be of particular concern to Australians that homosexuals in Papua New Guineans face up to 14 years imprisonment. Under current immigration policy Australia sends LGBTI refugees to the Manus Island detention centre and in July last year then Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus confirmed there would be no consideration for any group of refugees to be exempt.

As refugees at Manus are subject to PNG law any men in detention found engaging in homosexual intercourse may be reported to local police and subsequently face jail time.

In their 2013 report This is Breaking People, Amnesty International argued that these practices could constitute refoulement, a serious violation of international law under the Geneva Convention. Non-refoulement is the fundamental agreement to refrain from sending refugees to a place where they may be persecuted and is absolutely rejected by the international community.

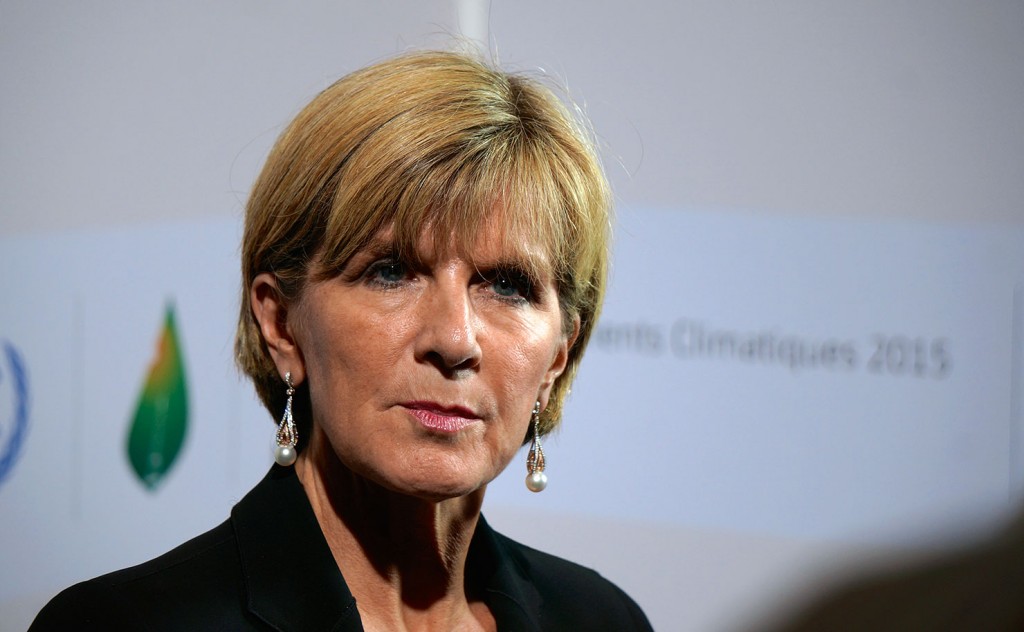

Similar problems exist in Nauru. Foreign Minister Julie Bishop has previously responded to concerns by stating “[We will] continue to work with Nauru — through bilateral and multilateral channels — to combat discrimination and promote the human rights of all people, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity.”

Though greater recognition of LGBTI rights in Australia and abroad can feel inevitable, some Commonwealth nations are deliberately moving in the opposite direction. The achievement of gay marriage in Scotland this month is in stark contrast to developments among a host of other member states, where criminalisation of homosexuality is becoming further entrenched.

In January 2014 the Indian Supreme Court upheld the restoration of section 377 under the Indian penal code which criminalises “unnatural offences”, long understood to be applicable to same-sex relationships. The 153 year old law was introduced under colonial rule and highlights the contentious position that colonial traditions play in national debates over tradition and values in post-colonial states.

In 2012 a Cameroon appeals court upheld a three-year sentence against a man found guilty of homosexual conduct for sending a text message to another man saying “I’m very much in love with you”.

In April the Syariah Penal Code Order 2013 will take effect in Brunei Darussalam, which will reintroduce the death penalty for offences including sodomy.

The reintroduction of the death penalty in Brunei can be seen as part of a trend in the Commonwealth. In 2012 Kaleidoscope Trust reported that 12 northern Nigerian states have introduced the death penalty by stoning for homosexual acts after adopting sharia law. Homosexual acts are similarly criminalised under secular law in Nigeria, however, the death penalty does not apply.

There have been several death sentences handed down since 1999, but there are no reports as of yet that any have been carried out. In February this year, two young men were subjected to 20 leather lashes for having gay sex. It was reported that members of the crowd outside the courtyard were disappointed over the “lenient” sentencing and were expecting the death penalty to be handed down.

In 2011, at the Perth Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM), then Foreign Minister Kevin Rudd’s attempt to promote decriminalisation of sexuality was a failure, receiving only the support of Canada.

In 2013, Prime Minister Tony Abbott attended the Colombo CHOGM and did not revisit the issue, despite the fact that Sri Lanka criminalises homosexual acts with up to 10 years imprisonment.

Julie Bishop’s recent expression of “serious concerns” over the Ugandan anti-homosexuality bill to her Ugandan counterpart was a positive step, however, Australia needs to further intensify its promotion of LGBTI rights.

Access to adequate health and education services for LGBTI communities, as well as rolling back criminalisation, is a pressing issue for the Commonwealth and a lot of work needs to be done. The 2015 CHOGM will be held in Malta, a state that does not criminalise homosexuality and could thus prove a receptive venue for reform.

To achieve results the lead-up to this summit will require an intensification of diplomatic effort by those on the side of human rights. The motion passed by the Australian Senate shows there is a will in Parliament to acknowledge the issue and to act – it’s a priority for them and for the Australian people.

If the Foreign Minister is serious about being a leader in non-discrimination it will need to be a priority for her too.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.