Yesterday the ABS released the December Quarter Consumer Price Index (CPI), showing that consumer inflation had risen from 2.2 per cent over the year to September 2013, to 2.7 per cent over the year to December 2013.

This means inflation remains within the Reserve Bank’s comfort range of 2 to 3 per cent, and it is in line with the Federal Government’s estimate in the Mid Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, which predicts it to be 2.75 per cent for the year to June 2014 before falling to 2.00 per cent next fiscal year.

So far so good for the Government’s forecasts, but it doesn’t take much analysis to see signs that inflation is on the rise. In the first half of 2013 inflation was low — 0.4 per cent in each quarter. In the second half inflation has much been higher — 1.2 per cent in the September quarter and 0.8 per cent in the December quarter.

If the rises of the last six months were to continue to June, inflation would come in at 4.1 per cent for the year, way above the Government’s predictions. That would be well outside the Reserve Bank’s comfort range and would be a cue for a rise in official interest rates.

Some of the big rises over the year have been in health (4.4 per cent), education (5.6 per cent) and housing (4.3 per cent). Housing utilities have risen by a whopping 6.8 per cent. But before we blame the carbon price we should remember that about 70 per cent of our electricity bill is for network and retail costs, which are not directly affected by the carbon price, but have been subject to significant price rises.

In fact, the biggest rise in utilities has been for water and sewerage (9.3 percent) — almost nothing to do with carbon pricing, but a lot to do with charges imposed by privatised utilities. Other big rises have been in alcohol and tobacco (5.4 per cent), reflecting higher rates of tobacco excise, and in child care (8.0 per cent).

Prices of most of these goods and services are highly influenced by government policy. If the Commonwealth is tempted to take up some of the recommendations of the Commission of Audit it will have a political eye to the effect on the CPI.

For example, a $6 co-payment for GP consultations would have a significant effect on the health component of the CPI. In general, any decisions which shift costs from government budgets on to consumers will raise the CPI. Similarly, decisions to privatise assets will show up in higher consumer prices for public transport fares, road tolls, utilities and other services, because private investors demand a higher return on capital than governments.

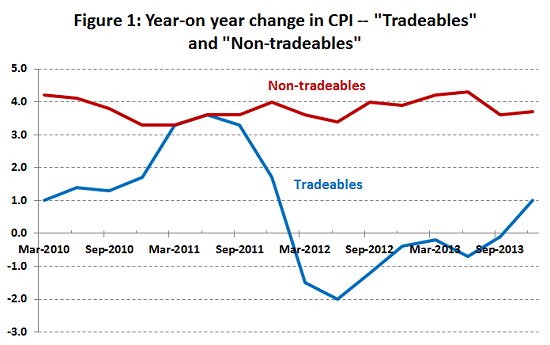

The other inflationary influence, which is well outside the government’s immediate control, is the exchange rate. Low-cost imports of clothing, cars, electrical goods and cheap overseas travel, by offsetting rises in domestically produced goods and services, have kept the CPI in check. The ABS decomposes the CPI into two components — “tradeables” and “non-tradeables”. As the names imply, the distinction is between imports (or import-competing items) and domestic products.

Figure 1 below shows that while domestic inflation has been kicking along at around 4 per cent, for the last two years' tradeables, which comprise about 40 per cent of the base of the CPI, have been offsetting rises in the non-tradeables.

Without the $400 Bali holiday, the $170 TV and the $6 knickers, we would have an inflation problem. Note, however, that the tradeables line has been moving up in recent times, and is now back in positive territory. In fact it would be higher but for unusually low gasoline prices in October and November. As anyone who has filled their tank in the last few weeks knows, they have resumed their upward trend. And in the highly competitive Christmas season retailers have kept prices down, but they cannot hold on forever.

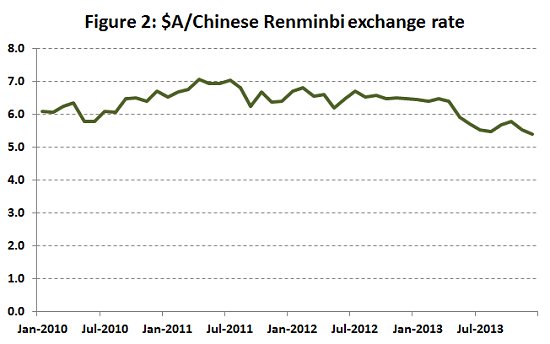

Most of the explanation for the price rises in tradeables lies in exchange rates. The Australian dollar is coming off its highs as the terms of trade turn back to more normal levels and as global growth picks up. Figure 2 shows the $A/Chinese Renminbi exchange rate over the last three years. (Because of the close links between the US and Chinese currencies a $A/$US chart would look similar.) Notable is the sharp fall (16 per cent) over the year to December 2013, from ¥6.5 to the $A to 5.4, and 5.3 at the time of writing.

Exchange rates are not the only reason we may be paying more for our clothes, appliances and other imports. Chinese wages are rising, and while production of low-tech items such as clothing has shifted to countries with lower labour costs, it is likely that China will continue for some time to be the supplier of more sophisticated manufactured products. Rising Chinese wages will flow through to prices we pay in Australia.

Many corporate economists expressed surprise at the high CPI, but the signs have been out there for some time. As with the poor labour market result last week, every piece of bad economic news is met with incredulity, as if now that the Coalition is in office and Labor has been kicked out, all must surely go well.

As for those who spent the last two years grizzling about imagined cost-of-living pressures and whose vote was influenced by a belief in the Coalition’s economic competence, 2014 may be the year of hard lessons, when cost-of-living pressures become a reality rather than a beat-up in the Murdoch press. They will be paying more for imports, may be paying more for health and education depending on the Federal Government’s Budget decisions, and those with mortgages could be hit with higher interest rates. They really will have something to whine about.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.