The Senate votes are nearly in. Never in Australia's history have so many political parties been represented in that room; 10, up from the previous record of six. Indignation directed at the minority in the House of Representatives is now directed up a storey. Accusatory fingers are being pointed at parties’ preference deals and the system that allowed them. Demands are being made for systemic change and a purer democracy.

But would a "fairer" system fix this mess?

It’s impossible to know how the current Senate would have turned out under a different preferential system. What is possible is a model of how the Senate might look under the other oft-mentioned reform: national proportional representation, a system in which to win one of the 76 seats, a candidate must win one 76th of the national vote.

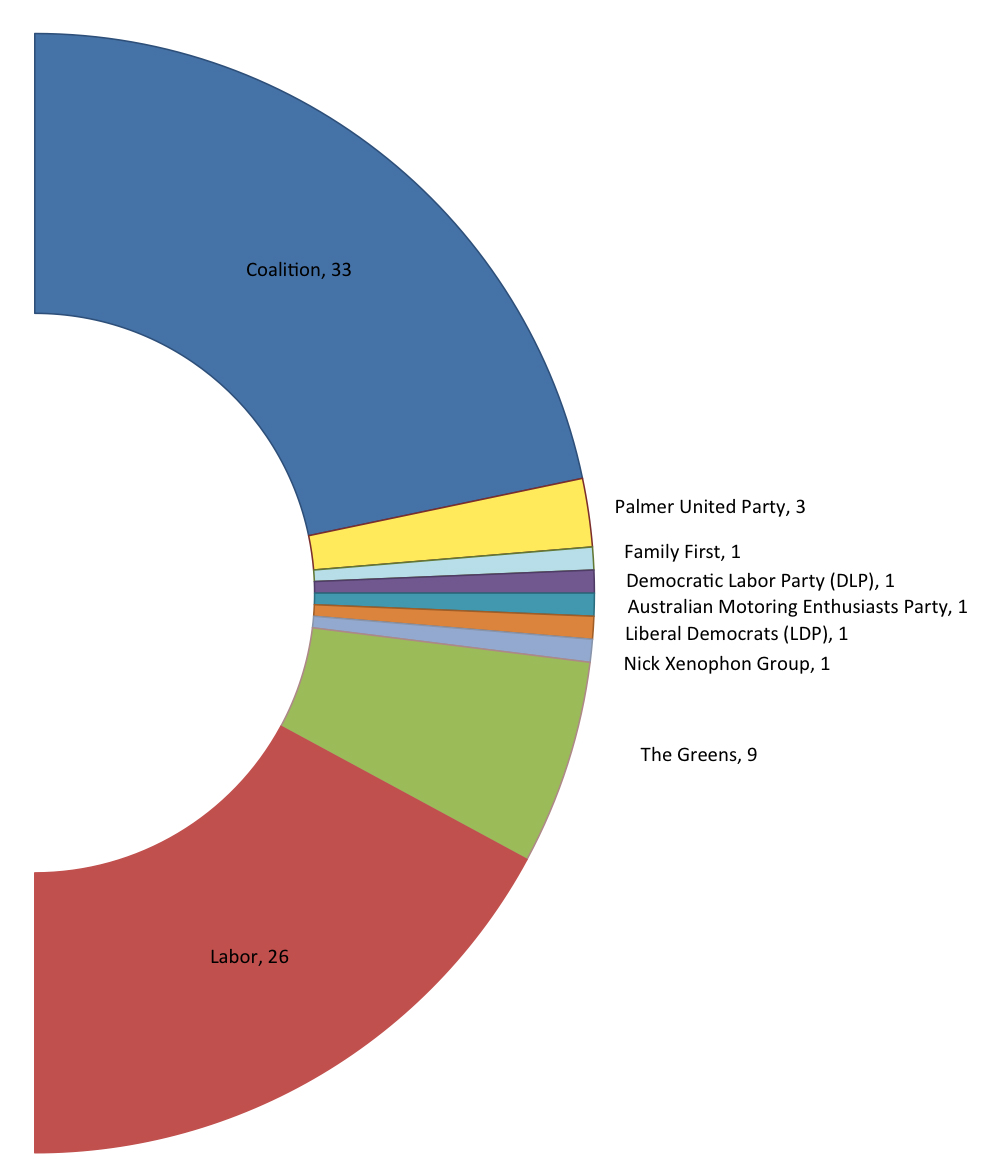

Here's the current Senate, notwithstanding a possible recount in WA.

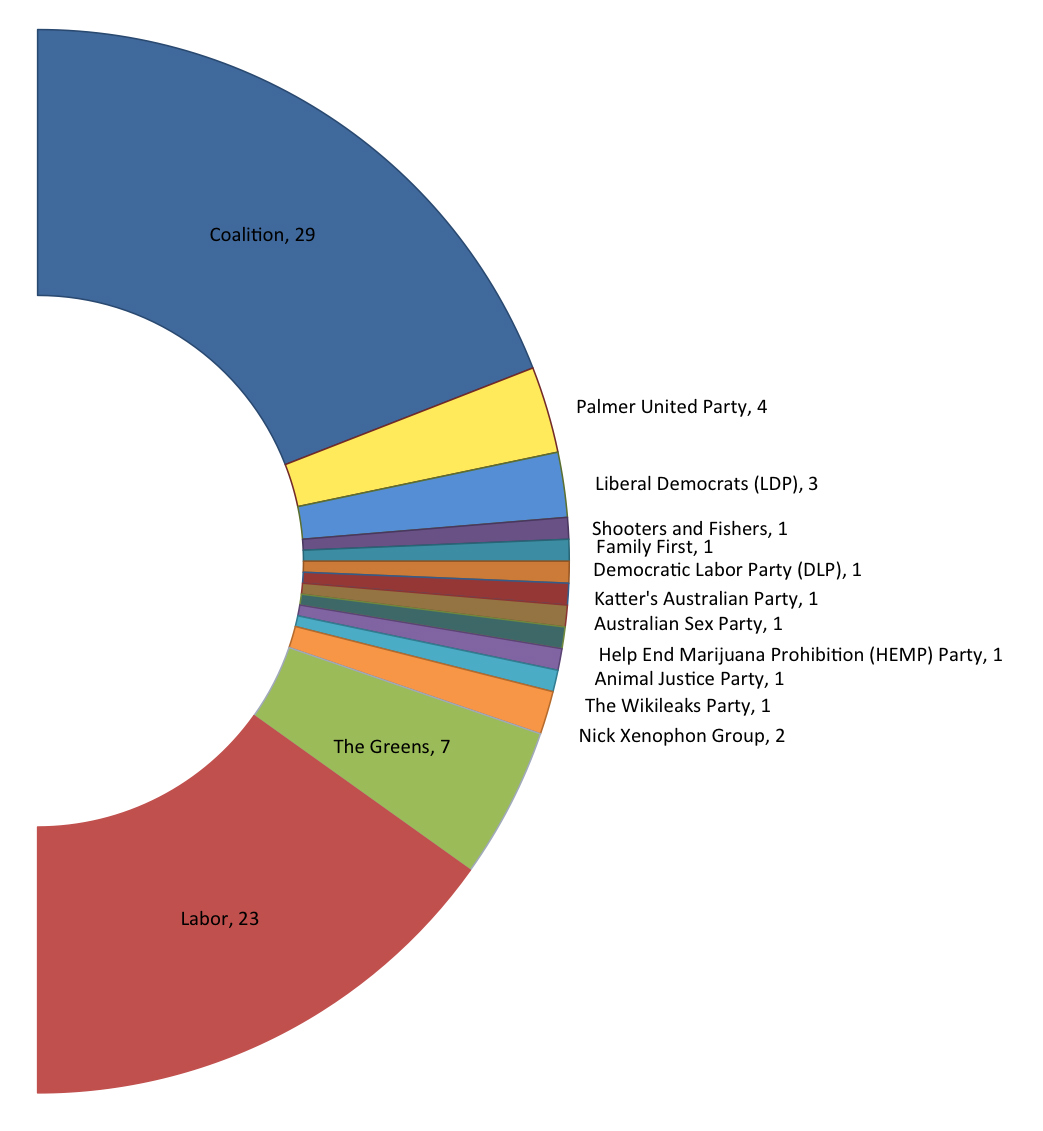

Here’s how it might have looked using the recent election results. (I've done a count of first preferences only, divided by 76 and rounded up (a "first past the post" count), for the purpose of practicality):

As you can see, the three largest parties would have fewer seats, while most of the most popular smaller parties would have more seats, with the rest remaining unchanged.

The reason for the difference is that the current system allocates each state 12 seats each. This means, as the most extreme example, if a voter registered in New South Wales has one vote, a voter registered in Tasmania effectively has 13 votes. Because the population is so much smaller, each voter wields more influence. Furthermore, this system means the votes of like-minded people in separate states can’t support the same candidate, and are instead passed along the preference chain, usually to a larger party. This means a party representing a smaller, but significant, minority (such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, the LGBTI community, religious groups, the disabled, or gun enthusiasts) is unlikely to win a seat in their without arranging preference deals with other parties.

How did the current system come about? For better and for worse, says Swinburne Politics Professor Brian Costar.

“The previous system was so undemocratic that it just couldn’t persist.”

In the 1930s, the Coalition held 33 of the 36 Senate seats. In the early 1940s, the balance swapped and Labor held 33.

“It was just massively majoritarian,” Costar adds. Labor knew they would be wiped out in 1949, so they created the current quasi-proportional system — whereby we only elect a half-senate per election — to minimise their losses.

“But it came back to bite them, because Menzies called a double dissolution election in 1941 and got control of the Senate.”

Labor hasn’t held a majority since. Costar believes having many “micro-parties” is problematic. “You need to somehow herd them in order to pass legislation. That’s going to happen after 1 July anyway.”

He points to the example of former Tasmanian independent Senator Brian Harradine who voted to, among other things, privatise Telstra (against public opinion) in exchange for restrictions on reproductive health issues, such as a veto on abortion drug RU486.

Greens Senator Lee Rhiannon says she isn’t bothered that proportional representation could disadvantage her party in the Senate. Although, she says her party’s priority is a proportional system in the lower house (which would deliver the party many more seats).

“It’s like we’ve hit the start of the 21st century and advancement of democracy has stalled. I think it’s stalled for a number of reasons. Because of the involvement of private money, people become very cynical about the electoral system and the government of the day.

“I think it’s important that democracy is revitalised, and one of the best ways to do that would be proportional representation.”

Rhiannon says campaigners in New Zealand worked for 10 years to pass their Mixed Member Proportional system by referendum in 1993. However a similar referendum in Ontario, Canada’s most populous province, in 2007 saw a 63 per cent vote against the change.

So what are its chances in Australia? Costar says it’s got Buckley’s. “[The major parties] wouldn’t go near that."

“And I don’t think there’s a lot of popular enthusiasm for it. I think, even less, when they see what they’re going to get with these micros. Some of these people didn’t expect to win; they’ve got no political experience — it’s going to be chaos.”

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.