This year marks the 30th anniversary of the formation of the Victorian AIDS Council, the organisation established by the gay community to spearhead the struggle against HIV/AIDS. It has been a time to remember those lost to the disease – but it has also been a time to celebrate. Thanks to the work of the VAC and the thousands of staff and volunteers and community members who listened to its messages and changed their behaviour, there are thousands of people alive today who would not otherwise be with us.

So, a celebration, for sure. A history, Under the Red Ribbon, has been released and a website launched. There’s the lecture series, the party, the launch, the poster exhibition … Well, you get the picture.

But the anniversary is also an opportunity to reflect upon how we got it so right – and how our success might help us tackle current social and political challenges.

At the very heart of the VAC’s work (and the work of similar organisations in other states and territories and at the federal level) was the idea that those most affected were the ones best placed to respond to the disease. The role of the government, the medical professionals, the health industry was to put their money and their expertise at the service of those who had the credibility to persuade gay men to take up safe sex.

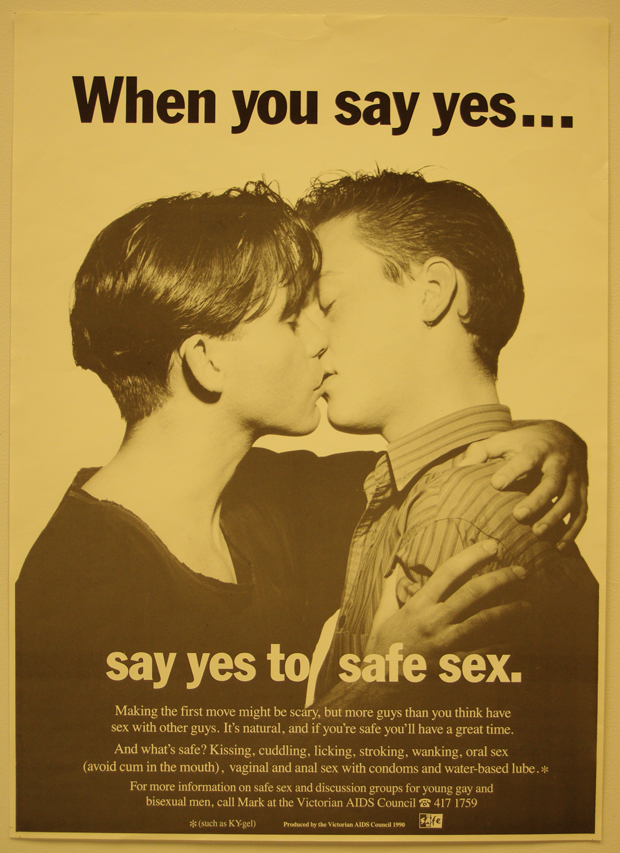

|

Image thanks to the Victorian AIDS Council |

In 1983, gay men were not going to listen to ministers, public servants, professors of medicine – most of whom knew less about the disease than did the leaders of the gay community anyway. But they were going to listen to people they knew, who they knew had been fighting for gay rights for a decade and who spoke in a language that made sense.

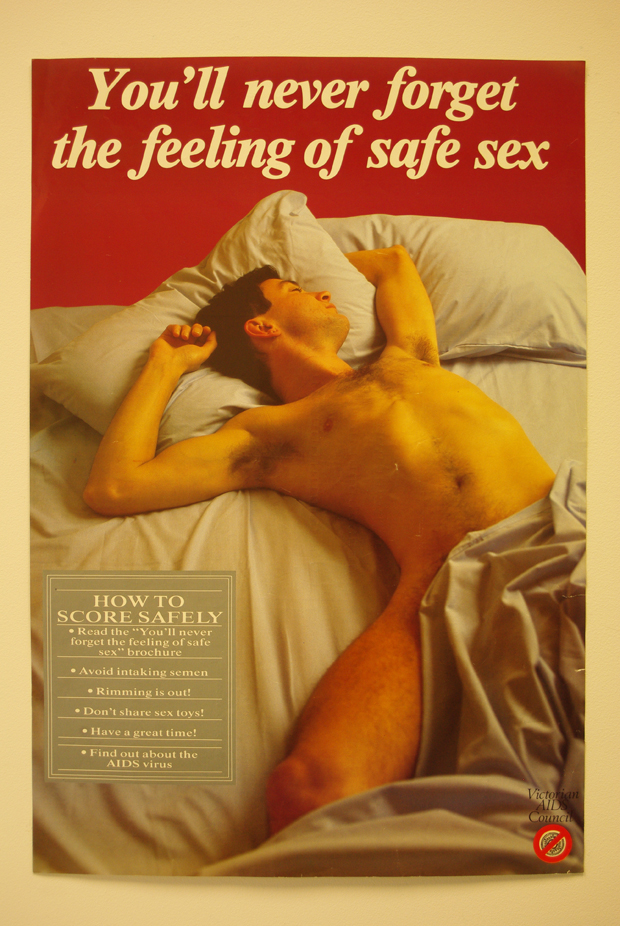

When VAC health educators and gay journalists started talking about gay sexual practices, they did not use words like “gay sexual practices”. They spoke in the much earthier terms that people used themselves. When they depicted safe sex, it was always in ways that affirmed it – safe sex was not a burden, but a pleasure. As the posters produced by the VAC over the years have never failed to remind us, safe sex is great sex, wherever and whenever it happens.

|

Image thanks to the Victorian Aids Council |

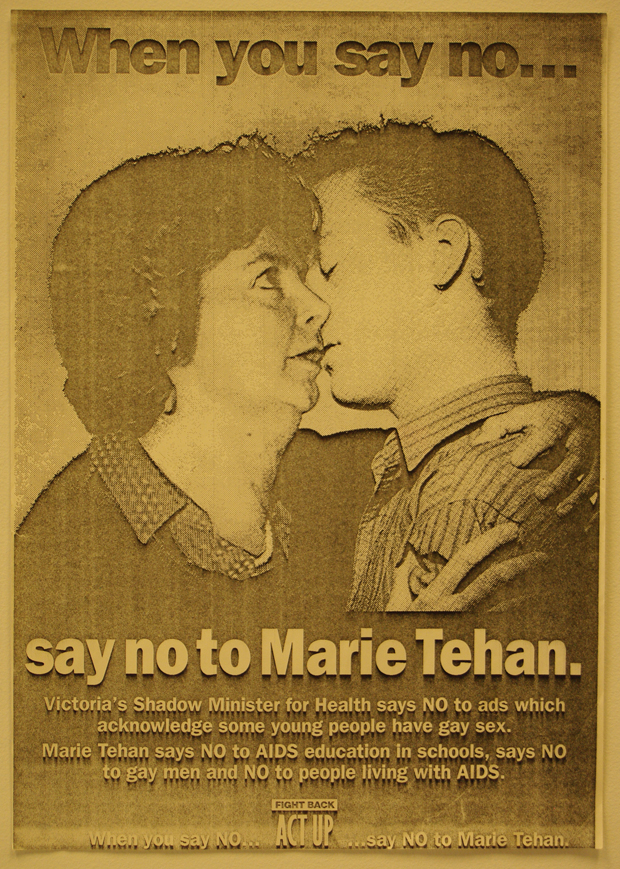

Much of this material could not be used in public. When the VAC produced a poster showing two young men kissing and declared that it was OK for young men to have sex with each other as long as you were safe about it (before going on to explain in detail what was safe and what wasn’t) there was consternation in some circles. The Victorian Liberal spokesperson on health described it as “scandalous” and demanded that the VAC’s funding be cut. The Advertising Standards Council ruled that it was unfit for publication.

The safe sex campaigns, funded by governments, but designed and delivered by those in the know, worked. They worked with gay men, and because they worked they were applied to other at-risk groups – to sex workers and injecting drug users. To women and straight men and to young people and Aborigines and migrants and the deaf.

Politicians mattered and the multi-party support helped state and federal governments, regardless of who was in power, do the right thing.

|

Image thanks to the Victorian Aids Council |

But courage was called for – and displayed. In the early years, ignorance and sometimes political opportunism fuelled demands for harsh measures. Ban gay rights marches; close discos, saunas and gyms; ban gays from working in schools, the food industry, libraries, public transport and even money handling; stop them travelling overseas. Only this would save innocent lives.

So, when federal health minister Neal Blewett stood up and denounced “AIDS hysteria” he was taking on a sizable proportion of the population and telling them they were wrong, and that there was a better way to deal with the threat.

It is this which points to the enduring importance of the 30 year campaign against HIV/AIDS. Imagine if we had responded to the challenge of AIDS in the way were are responding to the asylum-seeker issue. Imagine if we had seen ignorance and pandered to it; seen fear and stoked it; seen hysteria and crafted policies to appease it.

By opting to tell the truth to the electorate, to draw everyone affected (which was, in some ways, absolutely everyone) into the discussion, to rely upon trust and what we now call evidence-based politics, the AIDS campaign saw off the health threat posed by AIDS and the political threat posed by fear and ignorance.

It is a history that we can learn from still.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.