The case for a war against North Korea does not stack up, particularly not in the face of US-led aggression, writes Max Atkinson.

That North Korea is one of the most brutal regimes to have emerged from World War 2 was recently highlighted by the tragic story of US student Otto Warmbier and the bizarre murder of the President’s estranged half-brother, with strong circumstantial evidence of the regime’s complicity.

There was also the 2014 Report by the UN Commission of Inquiry into North Korea. In the words of its chairman, the distinguished Australian law reformer and former High Court judge Michael Kirby, the regime’s methods were “strikingly similar” to the crimes of Nazi Germany – he likened prisons to the concentration camps in which millions of Jews, gypsies and political prisoners were exterminated.

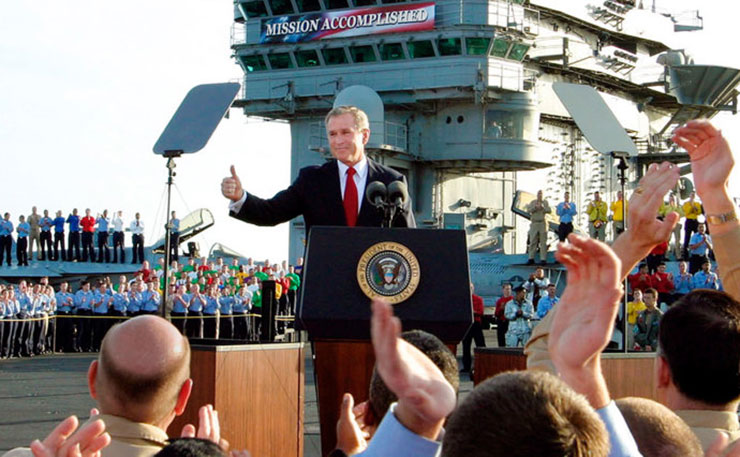

But these facts, appalling as they are, do not justify a war likely to kill thousands of innocent men, women and children. We should have learned this lesson from the Iraq War, when a US-led coalition invaded another brutal regime in a war which cost between 100,000 and 1 million Iraqi lives, and was later found to rest on fabricated evidence that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction which posed an imminent threat to Western nations.

While the US blames the crisis on the regime’s commitment to a nuclear defence, and the media focuses on its reckless missile tests and intransigence, little attention is given to a proposal by China and Russia, and supported by Germany and others, for a UN-supervised peace in which the North would end tests with a view to phasing out nuclear weapons in exchange for the US ending its own military exercises and phasing out trade sanctions.

But to better understand the North’s actions we need to go back to 1958, when the US installed nuclear missiles in South Korea in breach of the Armistice Agreement. They remained secret until 1974, when then US Army Chief General Creighton Abrams testified to Congress that the US had deployed a “tactical nuclear weapon”, the Lance missile, in readiness for a limited nuclear war.

It was not, he explained, to defend the South from the North, but for a wider, regional defence. This was in line with the Cold War containment strategy, first proposed by US diplomat George F Kennan in 1946.

According to Professor Lee Jae-Bong, an expert on the history of the period at Wonkwang University in South Korea, this left the North with a problem, since both the Soviets and Chinese refused to provide it with a nuclear defence and it could not rely on their support if attacked by the South.

That such an attack was a serious risk is confirmed by US files released years later and publicised by Chicago University Professor Bruce Cumings, an expert on the Cold War in Asia. Cumings, along with other post WW2 scholars, sought a more balanced account of US history in the region. The files reveal an ongoing concern that Syngman Rhee, the autocratic South Korean President, would re-ignite the war in an attempt to force the US to help unify the nation under his rule.

The missiles were withdrawn at the end of 1991, after the US and USSR signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty in July of that year to reduce nuclear arsenals by one third. The US has, however, consistently pledged since then that it regards South Korea as “under its nuclear umbrella”.

While it is unclear how much this US nuclear presence, together with the military exercises (now held twice yearly and meant to simulate an invasion of the North) has shaped DPRK policy, there is little doubt it would be seen as an existential threat by those who came to power in the period.

This feature, together with trade embargoes going back to 1950, suggest the regime’s provocations are a desperate if reckless attempt, after almost 70 years of exclusion from the community of nations, to force the US to negotiate a peace treaty to end the war.

One reason for US reluctance to engage in peace talks and a renewal of diplomatic relations has been the domestic political risk of talks with the enemy after a war which ended in stalemate and 37,000 US casualties. The risk is exacerbated by a retributive streak in US foreign policy which has seen trade sanctions in place since the war began. They were kept up against Vietnam for 19 years and against Cuba for over half a century until their relaxation by President Obama (now being reversed).

In each case US aims were frustrated by a small nation boasting Communist values.

This raises a question of the extent to which US policy is shaped by the demonisation of its former enemies, with a need to appease a public whose patriotism is largely defined by yesterday’s wars and ideological postures. How else to explain the economic isolation of the North, with biannual threats which force it to spend hugely on defence, with no hope of raising living standards? The main effect of this policy has been to reinforce the authority of a brutal dictatorship.

But the containment theory, based on forward defence, has its own logic, now seen in Eastern Europe since the collapse of the Soviet Union, with NATO allies extending from the Baltic to the Mediterranean, most willing to deploy US nuclear missiles to deter Russian expansionist aims.

Given a renewed emphasis on containing China, it is not surprising the US has no interest in renewing the six-power peace talks, which would see pressure on the US to withdraw 28,000 US military personnel along with its missile and bomber bases in the South.

The recent installation of Thaad interceptor missiles supports this view. They were brought in by the US during a transitional period after the dismissal of disgraced former leader Park Geun-hye and the South Korean election on May 9th, but before the new President Moon Jae-in, a former human rights lawyer, took office.

The US was well aware he had campaigned strongly against the missiles and, as the first non-US compliant President in decades, had promised to revive long-stalled peace talks with the North.

All of which suggests prospects for peace remain bleak as long as America refuses to discuss its own military exercises, insists on de-nuclearisation of the peninsula but not elsewhere in the region, and asserts a first-strike option.

Given US nuclear missiles based in Guam and Okinawa and B1 B Lancer bombers on patrol off the North Korean coast, the DPRK would have no deterrent against a 10-minute missile flight time and the threat posed by these bombers.

As a friend and long-time ally, Australia can make a useful contribution by working to calm tensions and promote peace talks, but not if it is joined at the hip to the US Administration, as Prime Minister Turnbull insists.

That metaphor sees Australia’s duty of loyalty as owed, not to the American people, and not to any principle of humanity or world peace, but to the personal aims and ambitions of a widely discredited US President.

PLEASE CONSIDER SHARING THIS STORY ON SOCIAL MEDIA: New Matilda is a small independent Australian media outlet. You can support our work by subscribing for as little as $6 per month here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.