Tony Abbott wants to make immigrants take the blame for our housing affordability problems, writes Ian McAuley.

Tony Abbott has an eye for complex public policy issues. He misses no opportunity to take a difficult issue – electricity supply, hate speech, the fiscal deficit – and make the issue even more complex and divisive.

In his speech at the launch of Making Australia Right, Abbott put forward his predictable “solutions” to all those issues (essentially a retreat to an Australia of the 1950s), and for good measure suggested that “we’ll cut immigration, to make housing more affordable”.

It’s not clear to whom he’s referring with his pronoun “we”. Tony Abbott himself (with licence to use the royal plural); a troika of far-right outcasts (Abbott, Bernardi and Hanson perhaps); or a Liberal Party heading to self-destruction under Abbott’s Trump-lite leadership?

But his idea has gained traction, according to the most recent Essential Poll. Fifty-seven per cent of respondents agree that the government should cut immigration to make housing more affordable.

But that “solution” won’t work – because it hasn’t worked so far.

As with so many economic issues, the price and availability of housing results from complex interactions of demand and supply factors. While most independent economists acknowledge this two-sided complexity, the Coalition, the finance sector, property speculators, real estate agents and land developers have all lined up on the supply side. Simply release more land on the urban fringes, re-zone inner areas for higher density housing, and all will be well. That’s that’s the voice of self-interest from those with a financial stake in expensive housing (way out on a limb of corporate self-interest, Ian Narev of the Commonwealth Bank doesn’t think housing is overpriced).

The reality is that while construction is booming – look at the sprawling new subdivisions as you drive out of our big cities, and at the cranes on new apartment towers – most “supply” of housing is in the stock of already-completed housing.

Those are the houses built over the last 100 years and more, and new construction will generally have only a minor impact on that stock. In economists’ terminology, the supply of housing is fairly price inelastic.

Also, because land release and re-zoning take a long time, supply-side solutions work very slowly. Although property developers see the task in terms of subdividing a bit of land on the urban fringe into 500 square metre blocks and providing a few pipes and local roads, there needs to be a network of supporting infrastructure.

New home owners and tenants – immigrant or native – do unreasonable things, such as sending their children to school and commuting to work by car or public transport. Adding people to cities incurs costs on all infrastructure users, and it’s not as if adding the seven millionth person to Sydney adds one seven millionth to those costs, because those costs don’t obey a linear function.

Old water pipes and sewers, to which new developments must hook up, have limited capacity. Adding just a few more vehicles to an already crowded freeway can convert a traffic crawl to a dead stop, imposing high costs on all road users and worsening local pollution. A few more people using suburban rail at peak times can increase loading-unloading times, causing delays that affect the whole rail system. Urban transport congestion is already costing around $16 billion a year, and that cost is projected to grow to $30 billion by 2030. Our cities do have problems in coping with a growing population.

So at first sight Abbott seems to be lining up with others on the demand side of the debate. The Labor Party and most independent economists propose a demand-side solution through some winding-back of negative gearing and capital gains tax concessions that have put so much money into the pockets of housing speculators (those in the Coalition prefer the more genteel term “investors”). Restricting the number of people seeking housing is another obvious demand-side approach.

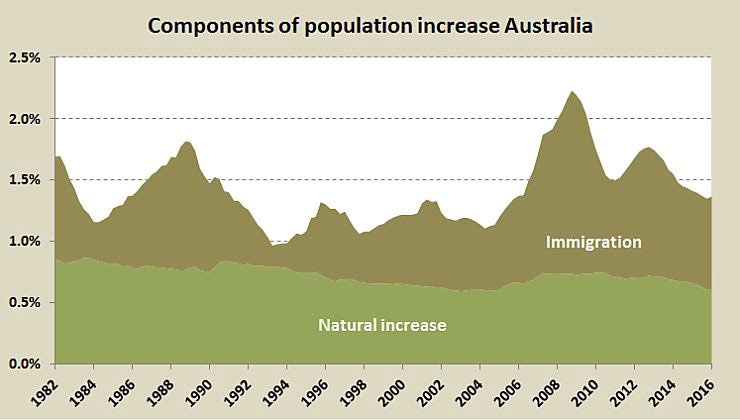

But the reality is that for the last eight years, immigration has been falling, as shown in the graph below, which is derived from ABS demographic statistics.

Not only has there been a fall in immigration, but also there has been a fall in the rate of natural population increase, and these falls have had no ameliorating effect on housing affordability.

That is not to say community concerns about immigration are unfounded. People living in our big cities are experiencing ever-stretched demand on roads and public transport systems, and it doesn’t matter where those extra drivers and passengers are coming from – Iraq, closed mining communities in Western Australia, China, rural Queensland – they’re all people adding pressure to our cities.

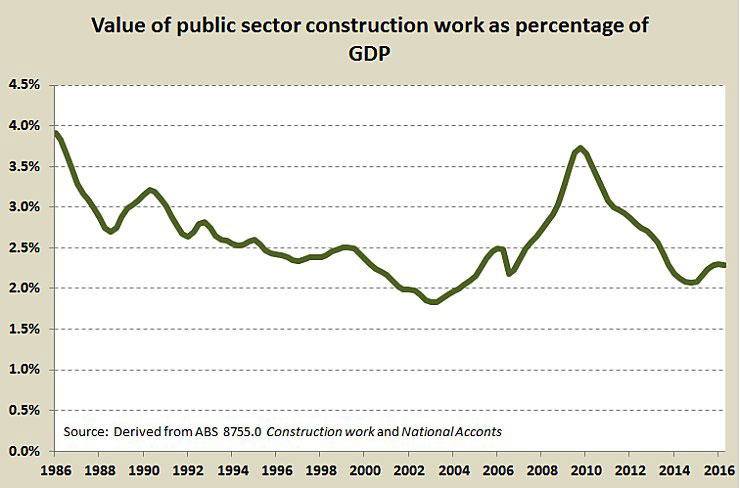

There are some impressive transport projects underway in our cities, but they fall short of what is needed, particularly urban metro rail systems that can bypass our congested hub-and-spoke systems. For all the talk about infrastructure spending, the fact is that apart from a short-term stimulus following the 2008 financial crisis, there has been a big fall in public sector construction work as shown in the graph below.

To avoid a backlash against immigration – and not just from racists energised by dog whistles from far right rabble rousers – we need urgently to invest in our urban transport infrastructure.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.