Australia is headed towards a recession, aided by a federal government that appears to know not what it is doing, writes Ian McAuley.

The National Accounts released last week confirm what economists already know: the Australian economy is in poor shape.

The headline news is the 0.5 per cent quarterly fall in GDP, the first fall since 2011 and the worst since the fall in 2008 following the global financial crisis.

This time there has been no global financial crisis. Rather it’s the outcome of poor government policy, over both the long and short term.

The main contributor to the poor figures is a fall in private and public investment.

Private non-dwelling construction is down by 40 per cent or $17 billion from its 2013 peak. Some fall was to be expected as the investment phase of the mining boom wound down, but in a more structurally sound economy private investment would have moved to other sectors. That hasn’t happened because the mining boom itself, through its exchange rate effect, inflicted enduring damage on our manufacturing and other trade-exposed sectors.

Treasurer Morrison is already using this poor result to push his government’s case for corporate tax cuts, on the spurious basis that Australia’s corporate tax rate, at 30 per cent, is uncompetitive by global standards.

The truth is that because of dividend imputation Australia’s effective corporate tax rate is much lower than 30 per cent. For a firm paying out half its profits as dividends (a typical long-term rate) it’s effectively 15 per cent.

In fact in recent times firms have been paying out about 70 percent of profits as dividends, meaning the effective corporate tax rate for domestic investors is now around 9 per cent. Unfortunately journalists, including those from the ABC, rarely challenge government ministers on this deception.

The reason firms are not re-investing their profits has nothing to do with corporate taxes. Rather it’s that in spite of very low real and nominal interest rates they don’t see opportunities for a return on investments. Corporate tax cuts, if they are to stimulate investment, do so by improving investment returns, in the same way as lower interest rates are supposed to operate. But if lower interest rates haven’t worked, lower taxes won’t work either. Perhaps Morrison doesn’t understand basic business finance, or perhaps his fear of losing has locked him in to a policy that will weaken public revenue with no economic benefits.

Firms aren’t investing because of poor market conditions and high risk, particularly the risk of policy instability.

Part of the explanation for poor market conditions lies in low growth in wages and other sources of household income. Over the year to September, nominal wages rose by only 1.9 per cent, barely ahead of inflation. Full-time jobs have given way to part-time jobs, which is why the national accounts continue to show a fall in total hours worked.

In view of what we have learned of under-payment of wages and superannuation in convenience stores, restaurants and the horticultural industry, and the use of sham contracting, it is probable that official statistics are understating the extent of the fall in wages.

When people’s incomes fall they buy less, particularly those people on lower incomes: that’s basic economics. It doesn’t happen straight away, because when incomes fall people get by for a time by drawing down savings and extending what credit they have available, such as “maxing out” on credit cards. Then they cut back on spending. That’s why our national accounts are only now showing up the results of two to three years of stagnant or falling incomes for most Australians. It’s only population growth that’s sustaining some modest expansion of domestic consumption.

And while market prospects are bleak, the policy settings for productive private sector investment are poor. We still have a capital gains system encouraging short-term speculation, particularly real-estate speculation, while penalising long-term productive investment.

As our ancient coal-fired power stations shut down we urgently need to invest in power generation and transmission, and to invest across the board to reduce the carbon footprint of buildings and other industrial establishments. These are inevitably long-term projects, and therefore need some assurance of policy stability.

But even though most of our elected politicians support sensible market-based mechanisms to deal with climate change, our government is held hostage by a small and unrepresentative group of economic morons. Continuation of this impasse is likely to see a strike of investment, leading to worsening domestic and industrial power shortages and electricity and gas price hikes, all while failing to meet our climate change obligations.

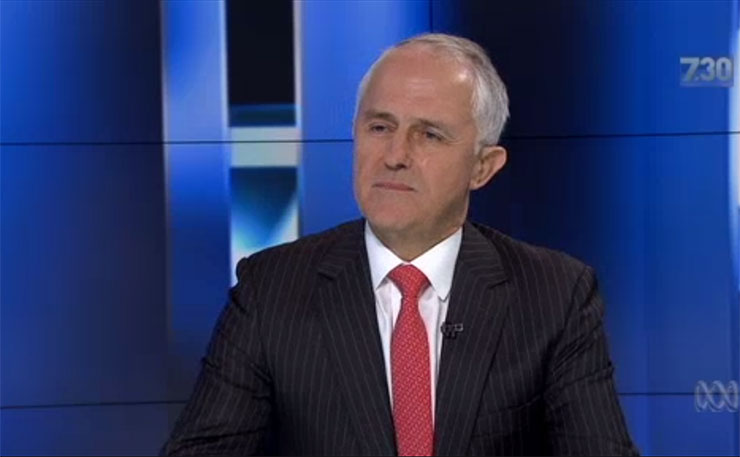

The Prime Minister and others in his party who have some economic competence could bypass the morons, and reach across to like-minded parliamentarians in other parties to develop a responsible energy policy. But they are so committed to the adversarial two-party system, and so blind to its deep-seated problems, that they are rejecting this opportunity to shore up their falling legitimacy. It’s as if Turnbull’s accountability is to a handful of far-right extremists rather than to the people who elected his government.

In a situation where private investment is falling we might expect an economically responsible government to step in with public investment. Economists of both “left” and “right” persuasion, and from conservative institutions such as the OECD and IMF, are urging governments to turn away from “austerity” and to stimulate growth – not through a “spendathon” of tax cuts and handouts (we’ve had too much of that), but rather through investment in productive public infrastructure.

In fact IMF deputy managing director Zhang Tao has said that increased spending on infrastructure would help protect our threatened AAA credit rating.

That’s not radical advice. It’s the same advice that may apply to a business losing profits because it has failed to invest in cost-saving machinery. Provided infrastructure projects pass muster on cost-benefit grounds, such spending (even if debt-financed) actually improves a government’s balance sheet.

We have the resources: the expertise and equipment employed in mining is the same expertise and equipment needed to build water and transport infrastructure. We have projects in need of funding – freight and passenger railroads, urban public transport, national highways, water conservation, broadband, schools. But the best the government can do is to promise to spend a billion dollars on a railroad to subsidise a foreign firm for an uneconomic coal mine that the world neither wants nor needs.

We will see in a couple of weeks, when the government releases the Mid-Year Economic and Fiscal Outlook, whether it can break from its debt monomania and start considering the health of the nation’s public balance sheet.

It is likely however, that out of economic ignorance, cronyism, or a visceral hatred of the public sector, the government will not veer from its destructive economic path of running down our public assets – our common wealth. And they will rationalise this quarter’s figures a mere “blip” in their otherwise successful “jobs and growth” program.

The December quarter’s GDP figures, which will come out in March, will probably show some growth, which means technically the “R” word will not apply. That’s because we will then be coming off such a low base – two successive quarters of 0.1 per cent decline would be a “Recession”, while one quarter of 0.5 per cent decline is not – figure that out! GDP in the next quarter will be boosted temporarily by the current high prices for iron ore and coal as steel mills replenish their stocks.

It will be later in 2017 when we see the flow-through effects of higher US interest rates, even if our Reserve Bank does not raise official rates. Then, at some time there will be a fall in capital city housing prices, which will be devastating for those who, encouraged by irresponsible government policy, have gone heavily into debt to buy “investment” property.

That’s when we will see a run of bad growth figures. It’s unfortunate that it will probably take a recession to convince the public that the Coalition Government’s claim of economic competence is groundless.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.