Free trade is rarely ‘free’, and the latest iteration could have profound affects on a nation that produces most of the world’s cheap, life-saving drugs, writes Megan Giles.

When Turing Pharmaceuticals acquired the US rights to the life-saving drug Daraprim, and subsequently hiked up the price by 5,000 per cent, the tsunami of online opprobrium was swift.

The former CEO and face of Big Pharma douchery, Martin Shkreli was excruciatingly smug and unapologetic.

He had a duty to his shareholders, he stated, and the “ugly, dirty truth” was that his actions were perfectly legal.

Those actions had given publicity to a long-standing debate, in the US and elsewhere, about access to affordable medicines and intellectual property rights (IPR), at a time when negotiations for Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) are seemingly weaving a web to cover the whole globe.

They also highlight, in a broader sense, the blatant absence of any moral dimensions to the World Trade Organisation (WTO), its primary purpose of which is to ensure that “trade flows as smoothly, predictably, and as freely as possible”.

Today, of course, there is a growing consensus that ‘free trade’ – the truly unimpeded flow of trade – is a myth, and a convenient and attractive phrase that is often used to justify competition between two unequal competitors.

Countries of North America, Western Europe and the Asian ‘miracle economies’, for example, all relied on careful combinations of tariffs, subsidies and other so-called ‘trade barriers’ to shield their domestic industries during their own development, however this luxury is rarely afforded to today’s underdeveloped countries.

There is no industry that so exemplifies the determination of life and death by corporate greed as pharmaceuticals.

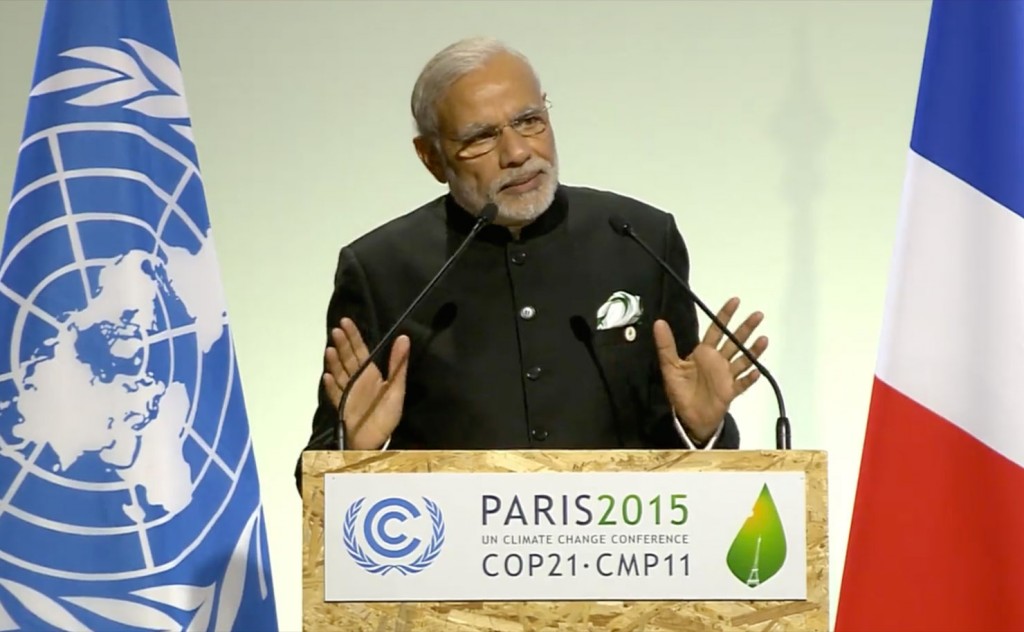

This week, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Brussels for the 13th EU-India Summit, in which negotiations for the pending EU-India FTA entered its ninth year and counting.

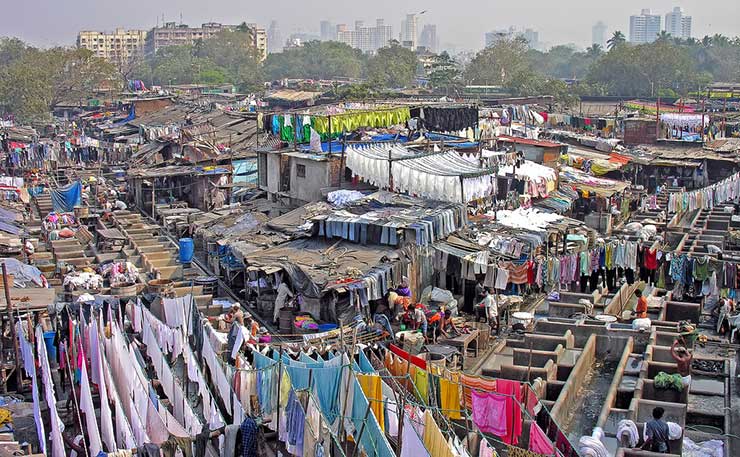

India has long been known as the ‘pharmacy of the developing world’, and international aid agencies have expressed concerns that provisions in the trade deal could restrict access to affordable medicines for millions of people.

In 1970, the country reformed its colonial patenting system and made the decision to exclude patents on pharmaceutical products. The Indian Patents Act, which recognised process patents and not the finished result, paved the way for domestic pharmaceutical companies to produce life-saving generic medicines, so long as they were created through alternative processes.

Within decades, local companies had control of 80 percent of the domestic market and became a key supplier of medicines to the global poor.

India supplies 70 percent of the HIV/AIDS medicines distributed by UNICEF, the Global Fund and the Clinton Foundation.

In 2001, Indian pharmaceutical company Cipla introduced the first ever 3-in-1 fixed dose treatment for AIDS and made it available for $350 per year (roughly a dollar a day per patient), rather than the $12,000 per year average in most countries.

Between 2001 and 2011, Eastern and Southern Africa – home to half of the world’s 37 million people living with HIV/AIDS – saw a 30 per cent decline in new HIV infections. This is thanks in large part to greater access to affordable treatment.

India’s generics have come under numerous threats, the first of which accompanied the inception of the WTO in 1995 and its Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement, which obliged members to include medicines in their patent laws.

After much furore by civil society organisations and developing countries, the worst provisions in the TRIPS Agreement were amended at the Doha meeting in 2001, allowing member states a limited interpretation of the agreement to ensure protection for public health.

In 2005, India passed changes to its patenting laws to include medicines, however taking advantage of the TRIPS flexibilities, it legislated for strict criteria for patentability; allowed for public opposition to patent applications; and asserted that generic-producing companies could apply for compulsory licensing from the government or patent-owner.

The momentum for developing countries was short-lived, however, as bilateral FTAs brought with them ‘TRIPS-plus’ provisions, allowing patent-holders to extend their monopolies beyond the 20-years contained in the TRIPS Agreement, which India would be obliged to enforce, in some circumstances, under a trade deal with the EU.

It remains to be seen whether Prime Minister Modi’s grand plans for India’s economic propulsion will include protection for an industry that is surely a source of pride on the international stage, or allow its steady erosion, which has already seen the recent absorption of six Indian pharmaceuticals by foreign multinationals.

Médecins Sans Frontières, which uses generic medicines to treat 94 per cent of HIV, TB and malaria cases – two thirds of which are made in India – has expressed growing concern over the EU-India trade deal.

A relentless grip on trade in life-saving medicines has resulted in numerous seizures of Indian-made drug consignments in the Netherlands and elsewhere in Europe, which were bound for Latin America and Africa.

Interpretations of several murky TRIPS Articles allowed for the seizure of goods in transit if the goods are suspected to be in breach of the transit country’s intellectual property laws.

India and Brazil (one of the intended recipients of the consignments) filed separate complaints at the WTO and were eventually awarded a guarantee in 2011 that the EU would no longer impede shipments of generic drugs in transit.

One of the main arguments made by IPR advocates is that intellectual property protection fosters creativity and innovation and ensures creators, authors, musicians or inventors receive due royalties for their works.

While this holds true in many cases, issues such as the patenting of biological organisms or pharmaceutical research become especially problematic when they hinder the global poor’s access to life-saving essentials.

Thomas Pogge of Yale University has argued that the “natural right” of inventors to exclusive benefit of their intellectual labours, particularly in seed patenting and pharmaceuticals, is dubious when considering their heavy reliance on publicly-funded research institutes.

“Not to speak of their broader reliance on the surrounding social infrastructure and the preceding centuries of human intellectual exertions,” said Pogge.

The argument that the privatisation of knowledge fosters creativity and innovation in biogenetic agricultural or pharmaceutical industries has also been disputed.

After examining the cases of more than 80 countries, the World Bank’s World Development Report 1998-99 found that intellectual property rights had an insignificant effect on the trade flows of high-tech goods.

Moreover, the history of India’s pharmaceutical industry under one of the most generic-friendly patenting laws in the world would show that relaxed IPR control has certainly not stifled innovation.

Back in the US, the cost of generic medicines has been skyrocketing.

Speaking in March at the United Nations Secretary General’s High-Level Panel on Access to Medicines, Yusuf Hamied, Chairperson of Cipla stated, “If we had today’s laws in 2000, I guarantee 100 million more people would have died from HIV/AIDS.”

Hamied points to the US, where the lack of competitive generic drug manufacturers has pushed medicines such an Albendazole, a parasitic worm treatment which is named on the World Health Organisation’s List of Essential Medicines and costs two cents in the rest of the world, to a hefty $240 a tablet in America.

Statistics from the US National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (DADAC) reported a 2,700 per cent rise in a generic blood pressure medicine, a 3,400 per cent rise in the asthma drug albuterol sulfate and a 6,300 per cent leap in generic versions of the antibiotic doxycycline – all in the span of one year from 2012.

While India has much to gain from a trade deal with its biggest trading partner, particularly due to potential export losses ahead of the impending Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), it will need to stand firm against the European bloc to keep the pharmacy of the developing world open for business.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.