ANALYSIS: In 1978 the real estate news was about a house on Sydney’s Elizabeth Bay that sold for $1.25 million – the first sale to clear a million dollars. That’s around $7 million in today’s terms.

Today a $7 million sale in Sydney would hardly be noticed. The record has been broken many times, most recently last year when James and Erica Packer sold their Vaucluse mansion La Mer for about $70 million.

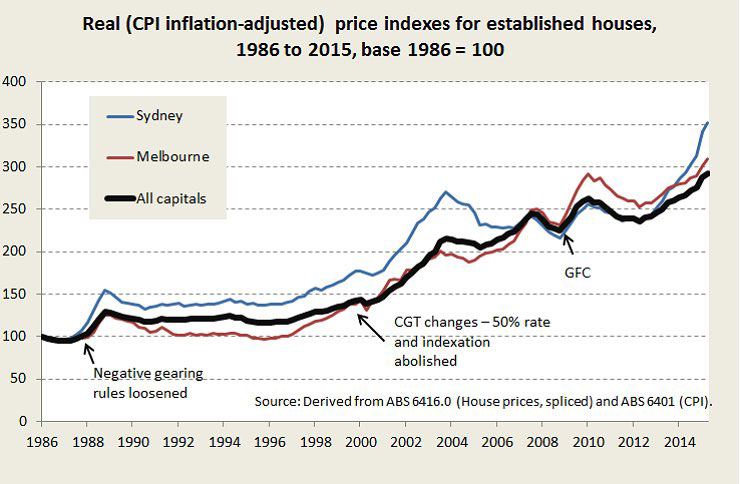

That tenfold price escalation has been at the top of the market, but over the last 30 years average house prices have trebled in real (inflation-adjusted) terms, and in Sydney the rise has been even stronger. Last year the median house price in Sydney broke through the million dollar mark – about 12 times average adult full-time earnings.

What the real estate industry may celebrate as a bull market, most Australians see as a problem in housing affordability. It’s a pressing concern not only for young people, but also for parents of young people seeking to buy their first house or apartment.

That’s why it was extraordinary to hear Malcolm Turnbull criticising Labor’s policies to restrict “negative gearing” and to change capital gains taxation. “The consequence of it will be a decline in property prices, every home owner in Australia has a lot to fear from Bill Shorten”, he said.

In what way would a fall in prices leave home owners worse off? If the market value of your house falls from $1.0 million to $0.8 million, or from $0.5 million to $0.4 million, it’s still the same house. In fact, if you are looking to trade up to a better house, a general fall in house prices would be to your advantage. Only if you’re planning to emigrate, or to trade down, should a fall in the value of your house be of any concern.

Was Turnbull simply counting on our ignorance? Perhaps he had in mind the young man who, on the evening of John Howard’s 2004 election victory, said to a roving TV reporter, “Of course I voted for Howard: three years ago my house was worth only $300,000; now it’s worth $500,000. I’m $200,000 wealthier thanks to the Government”.

Or was he really talking to those who hold “negatively geared” housing as an investment?

Either way, he’s denying the problem of affordability, and in implying that a Coalition Government won’t let house values fall, he’s giving false hope to housing investors.

Housing has its attractions to small investors because it is seen as real and secure. Rental yields may be low, but there is always the assurance of a capital gain. Also, thanks to the government’s permissive approach to “negative gearing” and short-term capital gains, it gives PAYG taxpayers access to tax rorts, similar in effect to those rorts exploited by small business people (family trusts and luxury cars classified as work expenses).

That, at least, is what many people believe.

Those who hold such an optimistic belief would do well to delve into the history of housing in Australia. As Dr Nigel Stapeldon of the UNSW Business School reminds us, there have been long periods, such as the 70 years between 1880 and 1950, when housing prices, in both real and nominal terms, hardly moved overall, and within that period there were sharp falls in the 1890s and 1930s depressions.

For the last 30 years the ABS has been surveying house prices, and that series is presented in the graph below, with the strongest markets, Sydney and Melbourne, singled out.

What’s clear from the graph is the strong (but rough) upward movement over the last 20 years. The market really took off after the Howard Government introduced its capital gains tax changes – changes designed to encourage speculation and turnover of assets.

Another notable feature is the big jump in the late 80s, when the Hawke-Keating Government, under assault from the real-estate industry, lost its nerve and reversed its earlier restrictions on negative gearing. On that occasion the market dispensed some justice to speculators, for the housing market remained flat for the next 10 years.

Twenty years of strong growth reinforces the “gamblers’ fallacy” – a belief that a lucky run will go on. It’s an irrational belief in a casino where the odds of a reversal have no connection with past outcomes, and it’s even more irrational in a bull market, where rising prices actually increase the probability of a reversal.

The party cannot last. Shorten wants to be the host who turns off the booze before everyone gets over the 0.5 per cent driving limit; Turnbull is the host who keeps the booze flowing – the DUI convictions and hangovers aren’t his responsibility.

The political problem is that, encouraged by rising prices, housing has become the choice for many small investors, displacing direct share investment, which has been going out of fashion. Between 2004 and 2014 the percentage of Australian adults owning shares in ASX-listed companies fell from 44 per cent to 33 per cent.

It’s an unfortunate trend, because investment in well-managed public companies is likely to see some real growth as those companies expand and innovate, while a house is simply a house – in fact, unless a lot is spent on maintenance and upgrading, it’s a deteriorating asset. Its capacity to hold value is entirely dependent on the value of the land on which it sits.

Also, apart from some adventurous people who take margin loans, small shareholders are not geared. While the stock market itself is volatile, its long-term trend is upward, and, unlike the highly-geared housing investor, the small shareholder can ride out market fluctuations more easily.

The small investor with a few parcels of ASX-listed shares has a stake in the nation’s prosperity. The heavily-geared housing investor, by contrast, has a stake in continuing housing unaffordability.

Small investors who want to balance their portfolios need something better than housing, and the opportunity going begging is for the government to issue infrastructure bonds to finance much-needed public works – a proper broadband network, clean energy, surface transport networks, water conservation – to name a few priorities where, for reasons of short-term or long-term market failure, public investment returns good dividends to the community, thereby providing tax revenue to pay bond holders.

Of course such investments would increase government debt, but, if wisely chosen, they would strengthen the public balance sheet. There is a world of difference between debt to finance recurrent expenditure and debt to fund productive assets: in recent years we have had too much of the former and too little of the latter.

As former US Treasury Secretary Laurence Summers explains, warning of the risk of “secular stagnation”, there is a lot of money sitting around in economies like the USA and Australia. That money should be channelled into something productive, rather than distorting the real-estate market. If firms are reluctant to invest then governments should take up the slack. In what should be sound advice to Treasurer Morrison, he writes:

It is true that an expansionary fiscal policy would increase deficits, and many worry that running larger deficits would place larger burdens on later generations, who will already face the challenges of an age-ing society. But those future generations will be better off owing lots of money in long-term bonds at low rates in a currency they can print than they would be inheriting a vast deferred maintenance liability.

Infrastructure bonds would provide an opportunity for Labor to redirect people’s savings to productive ends, while giving conservative small investors something safer than housing speculation.

They would also allow Shorten to lay legitimate claim to the title “infrastructure prime minister”.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.