Nothing justifies slaughter and nothing justifies degrading, inhumane treatment, regardless of where it occurs. But understanding why it occurs – and our part in it – is the key to putting an end to it. Dr Lissa Johnson explains.

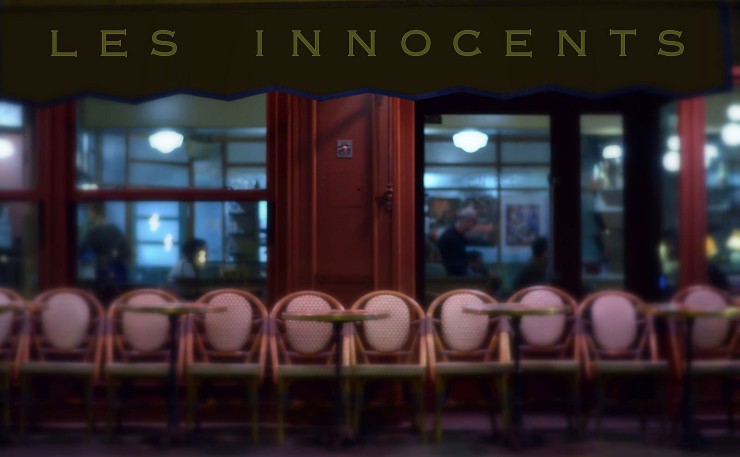

It is impossible not to feel horrified and deeply saddened by the abominable attacks in Paris last week.

This is from a man who lost his brother: “My brother left behind two sons and a daughter. They have lost their father in a terrible way. We do not know how to explain to them what happened to their father”.

This is from a mother who lost her son: “He had kissed me on the head before he went out. He was innocent. There is nobody in the world like him.”

A father described finding his son in “bits and pieces.”

The sickening grief and devastation is palpable.

It is so easy to imagine ourselves at a concert or a restaurant, in a city we know and love, unsuspecting one minute, our lives or our loved ones lives slipping away the next.

At the same time it is impossible to imagine what makes a person capable of such atrocity. What drives someone to commit such vile, vicious, cold-heartedly malevolent and destructive acts, against innocent human beings?

Given the brutal life-and-death stakes and the global war on terror, it is probably no surprise that psychologists have been trying to answer this question, most actively since 9/11.

In this endeavour, radicalisation and violent extremism are understood as multifactorial, and complex to psychologically unpack. Needless to say, “Personality, culture, or situational factors could [all]contribute to radicalization.”

Which is no surprise. Human beings are inevitably complex and frequently unfathomable, particularly where violent and nihilistic behaviours are concerned.

There is, however, an additional factor that renders violent extremism particularly challenging to comprehend, both inside the psychological literature and out.

It is blinding double-standards.

Take the following psychological account, for example:

“An important component… is the perceived superiority of the in-group: all other groups are perceived as clearly inferior… [and]people… start to develop a feeling of great distance toward people who live differently… Importantly, when people experience a distance to others, it becomes easier for them to inflict harm upon them. This may be particularly so when people no longer perceive out-group members as humans.”

“People … are [also]inclined to use violence when the ego of the group is threatened … [whether through]symbolic threat [to culture], realistic threat [to economic status], [or]intergroup anxiety.”

Or this:

“Ideologies are designed to justify the violence on moral grounds…through.. language that delegitimizes the targets of one’s violence, often by denying them human properties. The necessity of violence is premised on the notion that the enemy’s responsibility for harm (to one’s group) … stems from the target’s essential nature. Such presupposition portrays destruction of the enemy as … defense against the inevitable evil that he or she is bound to perpetrate.

Civilians are [seen as]potential combatants (they could be recruited or conscripted, thus becoming combatants in effect); furthermore, civilians are said to bear the responsibility for their government’s activities; in this sense, they aren’t neutral or innocent, hence they constitute legitimate targets for attacks.

[These] justifications of violence aim at portraying it as a morally justifiable and noble.”

Or this:

“Victimised peoples are not immune to becoming perpetrators as they seek to protect themselves. Memory of their own persecution makes them see potential dangers lurking in the future… Leaders often use the memory of the past to justify violence in the present… Unfortunately, because victims remember their past victimisation, they may feel justified committing violence in the present.”

And finally, this:

“Group members tend to defend their group when they perceive the value of their social identity to be threatened. Accusations that one’s ingroup has committed unjust harm against another group elevates ingroup protection processes, with ingroup members seeking ways of legitimizing their group’s harm-doing as a means of maintaining their social identity. An important means of justifying harm committed against another group is to view the harm as a defensive response to a threat posed by the outgroup.”

In short, people are thought to become capable of such atrocity when they “experience high levels of perceived injustice, personal uncertainty, and group threat”, leading them to dehumanise their victims and morally disengage.

It makes sense.

The problem is that only two of the above explanations relate to violent extremism.

The other two are explanations of American university students’ justification of US harm to Iraqis during the Iraq war, and opposition to reparations. These quotes explain indifference to human suffering and acquiescence to atrocity among ordinary, non-radicalised, law-abiding US citizens.

Can you guess which explanations are which? You probably have a 50/50 chance of getting it right.

It would be easy to fill the rest of this article with similarly interchangeable accounts of our own collective violence against other cultural and social groups (outgroups) and that of radicalised extremists. For instance:

“[A] crucial component [involves]social process of networking and group dynamics through which the individual comes to share in the violence-justifying ideology … Dehumanization and delegitimization of out-group members implies that killing them does not actually constitute encroachment on the killing prohibition that applies to humans.”

Or this:

“In particular, the enemy image includes perceptions of an outgroup as manipulative, opportunistic, evil, immoral, and motivated by self-serving interests.… As a result, the ingroup is perceived to be justified in taking action against the enemy group… To the extent that a group is seen as failing to uphold [ingroup]values, and thus is immoral, the group is likely to be seen as less than human, and thus as less deserving of humane treatment.”

The first quote relates to support for US military action and the latter to violent extremism. No. It’s the other way round. Or is it? Actually, one of them concerns attitudes towards asylum seekers.

Not that it matters. The meaning would remain the same.

In short, we know what makes people capable of unthinkable atrocity. Psychologists have understood it for quite some time.

Put simply, it involves an ‘us-versus-them’ mindset, in which ‘we’ are human and ‘they’ are not.

These processes are exacerbated by fear and intergroup competition, which are predictably exploited by leaders and popular media at times of crisis such as this.

Fear and intergroup competition breed not only outgroup hostility and dehumanisation, but also ingroup glorification and collective narcissism. Victims of ‘our’ violence are not only less human, but our violence is necessary and noble. Only ‘theirs’ is abominable.

The overlap in the psychology of our own and extremists’ group-based violence, however, is barely acknowledged in the psychological literature on extremism.

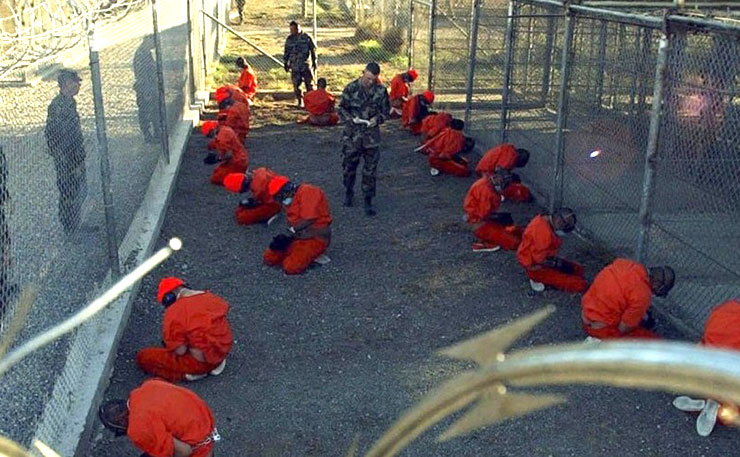

Where intergroup processes are described, there is little reference to their parallel role in ordinary law abiding citizens’ support for state-sanctioned violence (torture, war, military force, civilian death and injury), despite extensive literatures on the subject.

Rather, when applied to violent extremism, intergroup processes are often framed as particularly Islamic. They are described in terms of “Islamic youth”, “Islamic violence”, “Muslim extremists”, “prescription to obey the laws and rules of Allah”, the “extreme Islamic person”, “Muslim in-group superiority”, “Alienated and frustrated Muslims” and so-on.

Were the literatures on terrorism, radicalisation and extremism to acknowledge the shared psychological foundations with Western collective violence, two consequences might follow.

We would be forced to acknowledge that radicalised intergroup violence is not different, strange, unusual, unfathomable or foreign. Given the fierce hostility of global intergroup relations, particularly our and our allies’ devastating actions in the Middle East, group-based violence and hostility towards Westerners is predictable. And, unfortunately, human.

We would also need to acknowledge that our own intergroup violence is scarcely different. It is no more covered in glory, despite what our leaders and mainstream media would have us believe.

In the psychological passages above, for instance, while the third and fourth quotes relate to US citizens’ acceptance of US violence in Iraq, the sixth relates to contempt for asylum seekers and opposition to refugee intake in Canada.

Were we able to look past our own ingroup glorification we would see these very self-deceiving, self-defeating, base psychological processes at work in our own intergroup hostility, with origins in our very distant ancestors, whose knuckles still dragged along the ground.

Thankfully, some more evolved responses have prevailed in certain aspects of Australia’s response to the Paris tragedy. Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, for instance, has aligned himself with Islamic leaders to point out that Daesh “defame Islam”.

Grand Mufti Ahmad Badreddin Hassoun agrees, saying that Daesh “use[s]religious convictions as a pretext… to promote its political agenda [and]as a pretext for conflict and bloodshed… But this goes against the Prophet’s teachings.”

Australia’s Grand Mufti, Dr Ibrahim Abu Mohammed has also reiterated that “the sanctity of human life is guaranteed in Islam”.

However, a headline in The Australian on Monday read, “Paris Attacks: Our Politicians Must Confront Islamic Extremism” calling the attacks “first and foremost an Islamist attack on the West.”

It seems The Australian and Daesh are on the same page.

Equating Daesh with Islam not only helps some in the West to enlist anti-Islamic hostility and prejudice in support of national security border protection and war. It also helps Daesh to enlist recruits.

And it helps Daesh to motivate its members to commit atrocities under the false rubric of a holy higher cause. With the rationale that the end justifies the means.

We in Australia shouldn’t find that logic too difficult to understand.

Our own Prime Minster has said of our lethally brutal, internationally condemned human rights abuses on Manus and Nauru that our border protection is ‘tough’ (cruel, brutal, deadly, inhumane) ‘but it has worked’.

The end, in this case, also apparently justifies the means.

Moreover, we share with violent extremists a common ‘end’: territoriality and defence of cultural ideals and way of life. ‘Ours’ versus ‘theirs’.

‘Theirs’, wherever possible, is demonised.

For ‘our’ part, we brand asylum seekers illegal, Islam radical and dangerous and our military targets undemocratic, evil and unable to govern themselves.

In a parallel process, extremists have branded the US and its allies “God’s enemies”, “infidels”, “the great Satan” and “devil’s supporters”.

Psychologist David Mandel has noted the similarity between this language and that of George W. Bush as he garnered support for the Iraq war, repeatedly using the term “evil” and invoking a Godly “good versus evil” battle. Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott is partial to the same brand of rhetoric, which he has taken this tragic opportunity to unleash, in support of further militarism and demonization of asylum seekers.

While the language of our new PM is a welcome relief in comparison, Malcolm Turnbull has nevertheless maintained Australia’s legally dubious military presence in Syria, which forms an important part of the larger violent picture.

In the broader psychological literature on atrocity and collective violence, an aggressive approach to international relations is recognised as a driver of retaliatory terrorism.

This literature agrees with Australia’s Grand Mufti that “duplicitous foreign policies and military intervention” are “causative factors” in violent extremism.

In the International Journal of Psychology in 2006, Mark Mattaini and Joseph Strickland said, “the US has recently explicitly endorsed a strategic stance that relies on establishing supposedly invincible coercive power. This stance is precisely the one most likely to lead to counter-controlling actions, including terrorist strikes.”

Time, unfortunately, seems to have supported this view.

The continued bloody presence of the US and its allies in the Middle East, including Australia, only makes the West increasingly easy to demonise. Our actions have left nations razed to the ground, millions dead, and even more millions stateless and displaced, causing hunger, homelessness, illness, birth defects, power vacuums and armed, trained, radicalised militias all around.

Entire populations, as a result, live in terror daily.

Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton’s refusal to acknowledge this, and their combative responses to Australia’s Grand Mufti, provide living breathing examples of the very psychological processes described.

While Morrison and Dutton are up in arms, researchers would agree with Australia’s Grand Mufti that, along with militarism, “racism and Islamophobia” play a causative, violence-inducing role.

One difference in the psychology of violent extremism and Western collective violence is that radicalised individuals have often experienced actual, personal, lived injustice, social disconnection and threat (racism, discrimination, alienation, dispossession, war, displacement, oppression). For Westerners, in contrast, the intergroup threat and injustice are often predicted or anticipated.

What is truly remarkable in the psychology of intergroup violence is how readily we in the West can be manipulated to believe in the righteousness of our leaders’ deadly undertakings, no matter how thin or obviously dishonest their rationale. It is a vivid testament to the power and irrationality of the intergroup drive.

Even on cursory examination, for example, US claims of democracy promotion and defence of human rights in the Middle East fail to stack up.

One need barely look past the US (and Australian) friendliness towards Saudi Arabia, a regime as brutal and partial to state terror as any other. Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s supply of money and arms to terror groups all over the Middle East is well documented.

The US and its allies raise little objection to this, and the US continues to supply Saudi Arabia with money and arms, a fact that is similarly well known.

Going slightly further behind the scenes, but nevertheless in plain view, prior to becoming US Defence Secretary, Ashton Carter worked as a consultant for the defence industry.

Scholars are sceptical that it is possible for such a former businessman to “shift his outlook from protecting business interests to protecting the nation’s interest”.

Were the mainstream media less inclined to turn a blind eye and glorify their ingroup, they might consider this a matter of significant concern and interest. Particularly as Carter’s power over the US military is second only to that of the President.

Barack Obama’s use of drones might receive more scrutiny as well. Despite being credited with “targeted killing”, The Brookings Institute estimates that for every militant killed by a drone, approximately 10 civilians die.

According to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, as of September 2015 the US had carried out approximately 709 drone strikes across Pakistan, Afghanistan, Somalia and Yemen, killing up to 1,174 civilians and 220 children, and injuring many more.

That’s an awful lot of horror. And terror, no doubt, if you live where drones dwell.

Obama can’t have it both ways. If he wants the Paris attacks to be an attack on all humanity then our grief must be for all humanity, and all innocent victims, including his.

At a time when shock and bereavement reverberates across nations and borders we face an opportunity to think more deeply about the human consequence of international affairs.

After trauma, we as human beings are wired to learn from the devastating experience, to help us prevent the same thing from happening again, by understanding ourselves and the world better, that we might navigate it more wisely and safely in the future.

After bereavement we seek to honour the deceased, finding ways to carry their memory forward, holding on to what they have left behind, in the form of their mark on us and our lives.

In the aftermath of the Paris attacks we face a choice. We can harness the opportunity to increase our empathy for all victims of political violence, and take an uncomfortable but honest look at ourselves and our role in it all.

Or we can succumb to the very intergroup processes behind all intergroup violence in the first place – ‘ours’ and ‘theirs’ alike, as Francois Hollande would have us do. This, ultimately, means choosing more of the same.

On this path we share with terrorists the motive of revenge, which is recognised as a driving psychological force in violent extremism.

Is that how we would choose to honour the dead?

Now, more than usual, we feel the loss and pain of innocent victims. We viscerally stand in the shoes of the man who lost his brother, the woman who lost her son and the father who found his boy in pieces.

We share their desolation, even, hopefully, if told that their tragedy took place not in Paris but in Yemen. Even knowing that their loved ones were killed by US drones, not by Daesh bombs.

Like the victims of the Paris attacks, these people were going about their daily lives. They were innocent. Their survivors have lost the people they loved most in the world. They no longer feel safe. They are wracked by grief.

One survivor said, “everyone feels scared — children, women, men. Everyone thinks they could be the next target”.

A 15-year-old boy seriously injured in one of the drone strikes says, “When I hear aircraft flying in the air, it makes me panic and try to hide in any place. I constantly have nightmares of US aircraft attacking us: such nightmares disturb me while asleep.”

Other children in his village urinate at the sound of planes.

If we want to understand what took place in Paris, we can start by understanding our collective indifference to these children, and countless others like them.

And to our allies’ active, ongoing attacks on their villages, towns and cities. Which they may or may not survive.

As individuals we don’t have the ear of Hollande or Carter, but we can be the change we want to see in the world.

Including, crucially, supporting independent media that challenges rather than promotes collective violence.

It is a stand, and a start.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.