Scientists at America’s National Aeronautics and Space Administration centre are waiting with bated breath as nine years of work comes to the crunch with the ‘New Horizons’ space probe on track to fly by Pluto tonight.

It’s the first time humans have sent a probe to study Pluto, which used to be considered the ninth “classical planet” in Earth’s solar system but is now referred to as a ‘dwarf planet’, making it the first chance in a quarter of a century to study a new class of world.

New Horizons is scheduled to be the closest it will get to the frozen planet, around 12,500 kilometres above the surface, at approximately 8.45pm Australian Eastern Standard Time.

It’s been beaming the first colour images of Pluto back to Earth since April, when it was still more than 100 million kilometres away, but their quality has been improving as New Horizons hones in.

Despite having been in transit for nearly a decade New Horizons is the fastest spacecraft ever built, and its mission team boasts that it is carrying the most powerful suite of science instruments ever used to study a planet for the first time.

The probe will pass Pluto at a speed of around 14 kilometres per second, or just under 50,000 kilometres per hour, according to Queensland University of Technology astrophysicist Dr Stephen Hughes.

“That’s more than 10 times faster than a rifle bullet,” Dr Hughes said. “At that speed, you could fly around the world in 30 minutes!”

The probe may be travelling fast, but it’s so far away that the radio communications it’s beaming back to Earth take hours to reach NASA scientists at mission control, which is located at John Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland.

For most of the day New Horizons won’t be communicating with Earth anyway, instead it will be preoccupied with collecting a stream of images as it zooms by the dwarf planet.

More than 85 years since the small, cold and dark planet was discovered scientists expect to make unprecedented leaps in their understanding of Pluto as the images roll in over coming days.

The most recent revelation came this week when NASA, using images from New Horizon, revealed that Pluto is not blue, or grey, but red.

“Who’d have guessed a snowball like Pluto,” which ranges in temperature between -240°C and -218°C, “would actually be a reddish colour?” Dr Hughes said.

“Pluto’s colour is quite similar to the reddish brown of Mars, but unlike Mars, which is literally covered in rust, Pluto’s colouring is thought to be due to chemicals called tholins, which are produced when nitrogen and methane in Pluto’s tenuous atmosphere reacts with ultraviolet radiation.

“More recent images have shown some interesting features, including a long, dark shape that’s been dubbed ‘the whale’ [and]other images of Pluto’s moon Charon have shown us a newly-discovered system of chasms that are larger than the Grand Canyon.”

This is the first space mission that’s studied an entirely new class of world, which is neither a rocky planet like Mercury, Venus, Mars and Earth, nor a gas giant like the planets located in the solar system’s outer edge.

In fact, the dwarf planet more resembles other objects in what’s known as the Kuiper belt – a ring of icy bodies that extends beyond Neptune’s orbit – which is where New Horizons will head after it completes its flyby of Pluto.

“The Kuiper belt is similar to the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, only much, much larger,” said Dr Hughes.

“It could be home to as many as a billion icy bodies that are 10km in diameter or more.

“We believe these objects were made of the same material that formed into the solar system’s eight official planets but for some reason the Kuiper belt material stopped forming into planets quite early in the system’s history.”

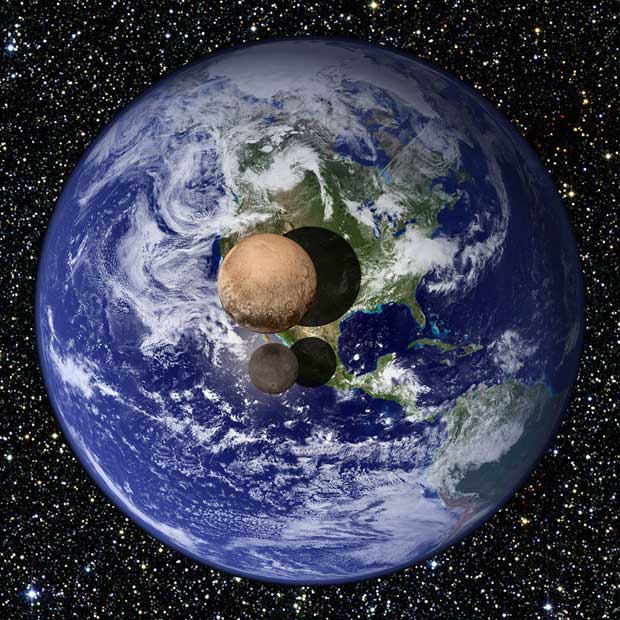

While it falls outside the Kuiper belt, Pluto’s mass is only around 2 per cent of the Earth’s and its radius is roughly the size of Australia. Scientists are hoping New Horizon’s new insights will provide clues as to the solar system’s distant past and help us understand more about the chemical ingredients of all planets.

Reaching this “third” zone of our solar system — beyond the inner, rocky planets and outer gas giants — has been a space science priority for years, because it holds building blocks of our solar system that have been stored in a deep freeze for billions of years.

New Horizons has travelled farther than any space craft humans have sent out into the ether, and after nine years of travel it’s designed to gather as much data as quickly as it can.

It will capture about 100 times more data on close approach than it can send home before flying away, but because it can’t stop to observe Pluto on its way to the Kuiper belt only the most high-priority data will be beamed back over coming days, with the rest to follow over a full 16 months.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.