Concerns over the Abbott government’s plans to “deregulate” the environment and give up much of its environmental powers to the states found a compelling voice this week, as revelations emerged that the Tasmanian government approved logging in contravention of expert advice, knowingly pushing an endangered bird much closer to extinction.

It’s the sort of industry-first approach that environmental lawyers and conservationists are concerned could become far more common under the federal government’s so-called ‘One Stop Shop’ reforms.

The policy would drastically diminish the federal environment minister’s portfolio and see state governments – which stand to gain much more from big developments, mining, and forestry – vested with assessment and approval powers over matters of national environmental significance.

The government says the ‘One Stop Shop’ will cut red tape without a drop in environmental standards but documents obtained by Environment Tasmania under freedom of information laws, released earlier week, have raised serious questions over the state’s commitment to conservation.

The Hodgman government has approved the logging of at least three out of five areas of forest which provide key breeding habitat for the endangered Swift Parrot, it was revealed, despite repeated advice from experts that it will hasten the species’ already steep decline to extinction.

“Conservation objectives for the species at the [local]and regional scales will not be met” if the areas are logged, scientists within Tasmania’s environment department warned.

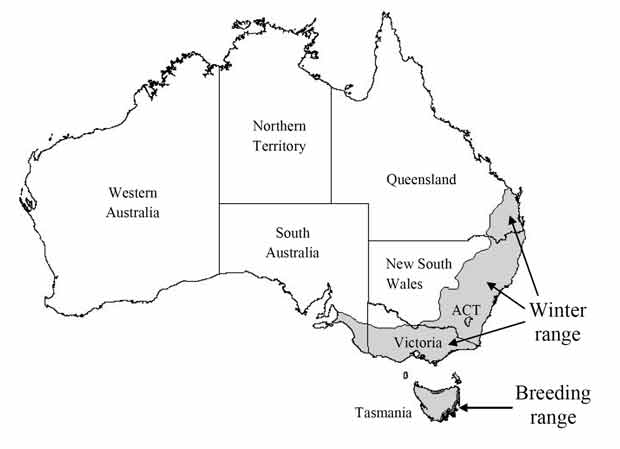

Less than 1,000 breeding pairs of Swift Parrot remain. Each year the bird undertakes the longest known migration of any parrot, to breed on the east coast of Tasmania.

The areas the Tasmanian government has now approved for logging are high-quality nesting habitat that are known to host large numbers of the just 2,000 remaining individuals during breeding season.

Cutting down forests in this breeding habitat, scientists within the department warn in one email, “will result in the continued loss of breeding habitat that has been identified as being of very high importance for the species with the further fragmentation of foraging habitat”.

“This cannot contribute to the long term survival of the species.”

Put simply, “there is no scientific evidence to support the position that continued harvesting of breeding habitat will support conservation objectives for the species”.

Ordinarily, where matters of national environmental significance such as threatened species are involved, the federal Environmental Protection Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act would be triggered and the Commonwealth government would be tasked with ensuring conservation outcomes are met.

For the Swift Parrot, though, there was no federal safeguard.

The Tasmanian government was allowed to issue the approvals, and ignore the expert advice, because of a deal with the federal government, known as the Regional Forestry Agreement (RFA).

It’s a deal that is remarkably similar to the wholesale hand-over of powers the Abbott government is pursuing through its One Stop Shop reform.

Tom Baxter, a corporate governance lecturer at the University of Tasmania, completed a PhD on the relationship between RFAs and the Environmental Protection Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act last year.

“Essentially, the idea of them was that they would provide basically for the states to agree to conduct forestry operations in the RFA regions in various ways and to reserve various land, essentially in return for the Commonwealth then largely staying out of forestry and leaving it to the states,” Baxter told New Matilda.

“It’s quite possible for Tasmanian forestry to drive a species to extinction without there being anything under federal law the Commonwealth government could do about it,” he said.

“The RFA has seen the federal government wash its hands of environmental responsibility.”

On Wednesday the Commonwealth refused to step in to protect the Swift Parrot.

“I think the One Stop Shop is taking national environmental law in a similar direction to that which the RFA has taken forestry,” Baxter said.

“Both essentially see the Commonwealth outsourcing its environmental responsibilities to the states.”

According to the Policy and Law Reform Director at the NSW Environmental Defenders Office, Rachel Walmsley, the federal government’s proposal to hand over its environmental powers to the states represents the winding back of 30 years of environmental gains.

Since the Hawke government famously fought the Tasmanian executive all the way to the High Court to stop the damming of the Franklin River in 1983, the federal government has steadily assumed greater responsibility for protecting nationally significant environments and species.

While the federal Environment Minister, Greg Hunt argues that "duplication of federal, state and local approvals processes adds complexity and cost to environmental approvals across the country with no added environmental benefit”, the Greens say that argument is a “sham”.

“There’s a whole lot of evidence that a lot of this stuff would have been sacrificed in the past,” the Greens spokesperson for the environment, Larissa Waters, said.

“Like the Great Barrier Reef, like the Franklin River, like the Mary River.”

The Abbott government claims the reforms will not compromise environmental standards, while saving business $426 million annually.

Claims around the monetary benefits of the scheme are debatable, but there is a relatively strong consensus that the Abbott government’s proposal will degrade existing environmental protections, which although stronger, have still overseen one of the world’s worst extinction rates.

The Greens have a written agreement with the Palmer United Party to vote against it, although it’s unclear how the disintegration of PUP might undermine that deal. Labor is standing against the current proposal, which the government needs to push through the senate in order to complete.

In December last year the ALP lodged a damning dissenting report, within a lower house Standing Committee on the Environment report, in which they accused the government of citing “the assertions of a select few industry groups to substantiate the report’s own assertions in support of this argument”.

The dissenting report also noted that recent research from the OECD had found that “the tightening of environmental policy stringency is found to have no longer-term effects on productivity growth”.

“Labor members agree that opportunities for streamlining state and federal assessment processes should be pursued, but only in a way that ensures that existing standards will be retained or strengthened,” the dissenting report says.

Few outside the Abbott government believe those standards will be maintained.

“We’ve found that no state or territory laws meet the necessary suite of federal standards that would be required,” Walmsley told New Matilda.

Her EDO colleague in the Northern Territory, lead barrister David Morris, said that the NT is under-resourced, its government lacks the maturity to administer the national standards, and cited the fact that 75 per cent of environmental impact statements sent to the Commonwealth are returned because they’re inadequate as evidence against the reforms.

These concerns over whether states and territories have the expertise, or the funds, to finance the more stringent environmental responsibilities are widespread.

Waters, who was herself an environmental lawyer for several years, says there are gaping holes in the Abbott government’s bill, which bely its rhetoric of “maintaining high environmental standards”.

“There’s a really clear section in there that says the states don’t have to reflect these federal standards in their laws,” Waters said.

“It’s in the legislation in black and white,” she said: “The federal government is saying that the states will comply with these standards but they’re then passing the law saying that they don’t have to.”

For its part, Birdlife Australia, an organisation which has led the decades long struggle to save the Swift Parrot through research, advocacy, and acting as the chair of a species recover team, says the Tasmanian Liberal government’s failure to protect the Swift Parrot also shines a light on broader problems.

“The bird is in serious trouble and it seems that governments at both levels – but particularly the Tasmanian government – seem to be actively, wilfully ignoring their plight,” said Sean Dooley, a spokesperson for the science-based conservation group.

“The fact that the Regional Forestry Agreement is exempt from the EPBC act is one of the main issues here.”

He says the Tasmanian government’s actions are not based on science, but vested interests.

“You have faith that by providing the objective scientific observations that they will be taken in to account: that just doesn’t seem to be the case and it doesn’t auger well for the future of environmental stewardship in this country,” he said.

“They just seem hell bent on ignoring the plight and you have to ask yourself why. The only logical conclusion is that protecting the timber industry trumps everything in Tasmania.”

Walmsley, Waters and Baxter are all concerned that the royalties and other benefits state governments derive from major developments might be driving their acceptance of the first stage of agreements, which are gradually being signed off on in an attempt to advance the One Stop Shop.

While assessment processes are already being conducted by states, the approval power still rests with the Commonwealth and there are concerns over what rights the federal government would retain to intervene if national standards aren’t being met, once approval powers are relinquished.

“We’re really concerned that even if their was a willingness on behalf of the federal government to intervene… they’ve now got one hand tied behind their back in terms of what action they can take,” Dooley said.

“It’s extremely concerning that this seems to be the model for the way forward with the One Stop Shop reforms.”

The government says it will set 100 standards that companies will have to meet, and it will maintain the right to set conditions if it’s not satisfied with those applied by the state.

It also claims to retain a ‘call in’ power “for proposed projects that will result in, or are likely to result in, serious or irreversible damage in breach of the agreement” up to the point of approval.

Compliance and monitoring of conditions after an approval will be passed off to the states.

The federal Environment Minister, Greg Hunt, did not respond to repeated requests for comment, but given that agreements won’t necessarily require states to conform to the federal standard, it is uncertain how the ‘call-in’ provision would operate.

Commonwealth moves to delegate its responsibilities are “problematic [for]Australia’s international treaty obligations through which we’ve promised to protect threatened species and World Heritage,” too, according to Baxter.

In the face of these many apprehensions – which were only exacerbated by Environment Tasmania’s revelations about the plight of the Swift Parrot this week – a founding father of Australia’s environmental law offered some advice at a Law Council symposium on the topic earlier this month.

“Experience suggests that these ‘downturns’ are common, particularly in times of conservative governments; and there will be a rebound,” Dr Gerry Bates said.

“I never forget the times when, you know, walking along Northumberland’s beaches these oiled sea birds would just come struggling up the beaches absolutely unable to swim, hardly able to move,” he said.

“A number of us took to capturing as many of these oiled sea birds as we could, cleaning them, and if you were really, really lucky, six weeks later you could release them back to the ocean.

“Most of them didn’t make it, because as soon as they ingested a small amount of oil, they were doomed and it took a few weeks for them to die.”

Bates said the trajectory for environmental protections in Australia, though somewhat cyclical, has been one of improvement over recent decades.

For many experts, though, the One Stop Shop reforms represent a dramatic 30-year regression.

Just days after it was revealed Tasmanian authorities had ignored the expert advice, a paper from researchers at the Australian National University urged the government to list the Swift Parrot as critically endangered and warned that numbers could halve in just four years.

There’s a deep awareness amongst those working in the space that, even with the preferred current laws, species like the Swift Parrot are on a trajectory more like the oiled sea birds, and the species can’t rebound from extinction.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.