While it’s easy to blame Aboriginal parents and communities for failures in black education, a new paper turns the spotlight back on teachers, who need to be schooled on how their ingrained beliefs can entrench low expectations in Aboriginal students.

The Stronger Smarter Institute released a new position paper today outlining a pathway to implementing its philosophy of “high expectations relationships” in Aboriginal education.

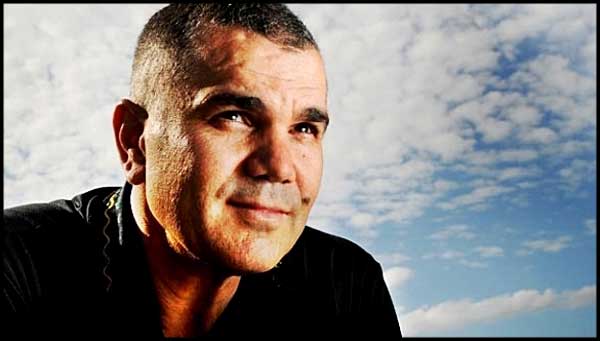

The paper is based around research by people like Dr Chris Sarra and David Spillman, among others, and the experience of the Institute in schools across the country.

It also warns against government policy and media discourse which positions Aboriginal students and parents as failures, and blames them for their disadvantage.

It finds that many Aboriginal students battle negative perceptions of themselves, which foster low expectations and act as roadblocks to success.

While some teachers and schools may talk about fostering “high expectations relationships” in Aboriginal students, there is often a failure to walk the walk, the institute says.

According to the Stronger Smarter Institute, often teachers can bring “underlying and ‘out of awareness’ beliefs and assumptions” into classrooms, stemming from the fact the majority of Australian teachers are drawn from Anglo-Australian middle class backgrounds.

“Historically, Australian society has conditioned us to have low expectations of Indigenous students,” the paper says.

“In Australia, high expectations for Indigenous students has too often been built on ‘deficit’ thinking and interpreted as meaning students should be ‘mainstream’.

“The deficit positioning of Indigenous people is strongly reinforced in education through the language of ‘disadvantage and the discourse of progress and enlightenment.’”

Sarra and Spillman argue that often, teachers come into classrooms unaware that they are fostering low expectations in students.

“The socialising processes of a middle class upbringing, reinforced by the implicit rules and norms of schooling, are so powerful they appear to be largely resistant… to understanding diversity,” the paper warns.

These “out of awareness values and beliefs” lead to “habitual patterns of perceiving, thinking, judging and behaving”.

“It’s in this way that society has conditioned us to have low expectations of low SES and Indigenous students, also highlighting why it can be very difficult to change such perceptions and judgements even for those who genuinely believe in high expectations for all.”

It says teachers can also fall into the trap of short-changing Aboriginal students and “racism by cotton wool” occurs.

“In the absence of (Indigenous) knowledge, teachers wanting to do the right thing but afraid of getting it wrong take an easy option. Classrooms disengage students, they don’t receive a high quality delivery and students are ‘lured’ into accepting mediocre standards.

This can mean teachers give easier homework to Indigenous students, or accept absenteeism.

The institute warns that the solution is complex and the role of a teacher is more than “simply a deliverer of content”.

Currently, there is a move to embrace Direct Instruction (DI), an American-style form of teaching advocated by Cape York lawyer Noel Pearson as part of his Cape York Welfare Reform trials.

Under the DI model, teachers follow scripted lesson plans for students. It has been widely criticised by educators, notably by Dr Sarra, who said it took away the human connection from child and teacher.

The paper also warns away from negative public discourse which blames blackfellas.

“Public discourse around educational underachievement and failure frequently relies on deficit accounts that attribute blame to disadvantaged groups,” it says.

The Abbott government has spearheaded a campaign against truancy in Aboriginal communities, stationing school attendance officers to round up children and get them to school. It has also continued the controversial School Enrolment Attendance Measure (SEAM) in the Northern Territory, which links school attendance to welfare payments and punishes parents if their kids don’t’ attend school.

A report from the Australian National Audit Office last year found impacts of previous SEAM trials on attendance rates were often unclear or proved temporary. Positive effects from SEAM in the NT was “anecdotal” and the reporting measures had “limitations”.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.