Here, in Collins St, who is protecting us as we sip wine, nibble canapés and listen to Rushdie talk about freedom of expression?

When, on 29 August, Herald Sun literary editor Blanche Clark penned a strange, solipsistic, (‘Today, in Collins Street, it just got personal’) response to Salman Rushdie’s Melbourne Writers Festival event, social media erupted in hilarity.

What a difference a month makes.

Suddenly, Clark’s piece sounds entirely unexceptional.

Suddenly, all the serious pundits think terrorism’s ‘got personal’; suddenly, everyone demands protection, whether at the Grand Final, in train stations, or at Parliament House.

So was Blanche Clark right? Or is the panic now as foolish as the panic then?

Insofar as Clark based her fears on anything, she relied upon figures from the Global Terrorism Database: they showed, she said, “more than 125,000 terrorist events between 1970 and 2013, including 58,000 bombings, 15,000 assassinations and 6,000 kidnappings.”

So let’s look at that data. The University of Maryland provides a tool for visualising the GTD in different ways.

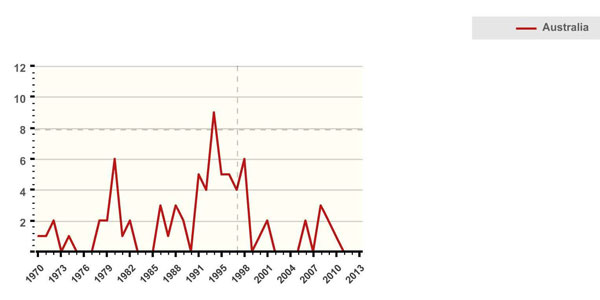

For instance, here’s a graph of ‘terrorist events’ in Australia from 1970 to 2013.

The figures are so low that it’s impossible to identify any particular trends. Nonetheless, if we add the two most recent ‘events’ – the arrest of Omarjan Azari in Sydney and the shooting of Numan Haider in Melbourne – it’s obvious that we’re scarcely in the midst of a terror upsurge. On the contrary, terrorism in Australia remains what it’s always been: an entirely marginal phenomenon.

The database provides an empirical demonstration of what should be obvious – simply, in respect of terrorism, Australia remains one of the safest countries in the entire world.

Go to the site and look yourself. The tool allows you to chart terrorism incidents in nations around the world. Try to find a country anywhere in the world with a lower incidence of terrorism than Australia.

Naturally, that doesn’t mean attacks are impossible.

Even in Australia, no-one can guarantee your absolute safety at all time. But that applies to other risks, as well.

If you’re attending a glitzy event in Collins Street, the canapés might make you ill. It’s possible. Food poisoning kills far more Australians than terrorism (which hasn’t been responsible for any Australian deaths in this country since 1978). But no-one insists that the MWF provides a portable stomach pump next to the buffet.

We’re never entirely, 100 per cent safe, whatever we are doing. Yet most of us go about our business all the same.

Or at least we did until recently.

In Foreign Policy, Rosa Brooks (riffing off Stephen Colbert) identifies something she calls ‘threatiness’.

“Sometimes,” she says, “we cannot articulate why something is a threat, or offer evidence, but we still think it just feels, you know, threaty. We know it in our gut. And let me be clear: when there is enough threatiness floating around, America must take action.”

Australian leaders have a nose for threatiness, too.

Today, Tony Abbott says the Islamic State has “declared war on the world”. George Brandis says the group represents an “existential threat”, more dangerous than that posed by the nuclear-armed Soviet Union during the Cold War.

In the Sydney Morning Herald, Shane Green says that Australia is “at the centre of the terror threat posed by IS.”

With the greatest of respect, all this is nonsense.

We have seen two incidents, only one of which involved injury. Yes, Numan Haider stabbed policemen before he was killed. But the centre of the terror posed by IS remains Syria and Iraq. It’s grotesque to compare the danger posed by one teenager with a knife to the carnage taking place in countries gripped by civil war.

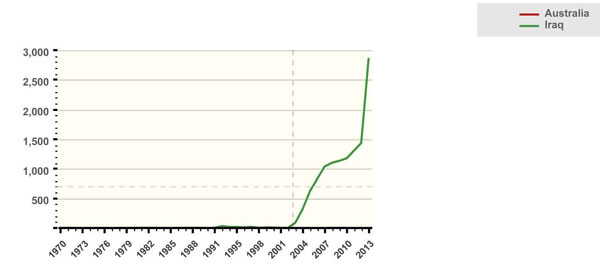

But don’t take my word for it. Here is a graph of terror attacks in Australia alongside those in Iraq.

As you’d expect, the Australian figures disappear into the bottom axis of the chart, invisible next to the everyday mayhem taking place in Iraq.

But note the two spikes in the chart – the first in 1991 and the second (and far more dramatic) in 2003. Those dates mark, of course, the two most recent wars against Iraq, both of which involved Australia.

The local media tends to present terrorism as a phenomenon directed, first and foremost, against Australians. The statistics show a very different story.

Insofar as Australia features in the global narrative of terrorism, it’s primarily through participation in the military interventions that send terror incidents skyrocketing in the countries we attack.

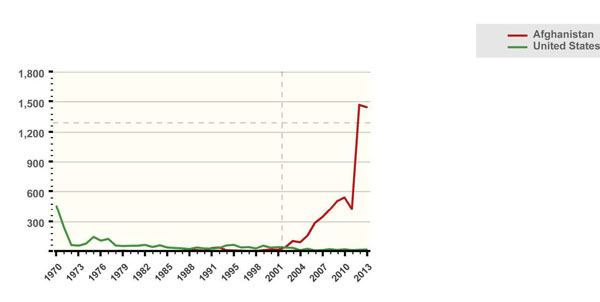

Let’s look at an even more telling comparison: terrorism in the US versus terrorism in Afghanistan.

That chart records the dramatic long-term decline in terrorism within America (a trend even clearer in isolation) – and a steady increase in terrorism within Afghanistan in the wake of the US-led invasion of 2001.

Why is this missing from the current debate?

As Australia enrolls in a third war in Iraq, it’s tempting to dub the peculiar myopia about terrorism in other countries as ‘Tom and Daisy syndrome’, after the famous passage from The Great Gatsby:

They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made…

Australia’s a rich country, enjoying one of the highest standards of living in the world. With that prosperity comes a heightened sensitivity to entirely marginal threats against us – and a Tom-and-Daisy like indifference to the consequences of our own actions elsewhere.

You can see it in the desultory discussion about what the latest military mission will mean for the people of Iraq and Syria. This is one of the strangest interventions in living memory, a campaign in which the Americans (and, by extension, Australia) are engaged in tacit co-operation with a designated terrorist group (the PKK), a vicious dictatorship (the Assad regime) and a member of the old Axis of Evil (Iran), all in the name of humanitarianism.

The influential Shiite leader Muqtada al-Sadr – whose militias are currently fighting the Islamic State – has been calling demonstrations against the deployment of American ground troops. At one of these recent protests, Deputy Prime Minister Bahaa al-Araji publicly claimed that the US was behind the IS, while other demonstrators burned American flags.

What will result from such a tangled skein of enmities and alliances? Is it not in fact entirely probable that military strikes conducted in such a fashion will not replace the ghastly Islamic State with peace and stability but will rather prepare the ground for more misery, much as the overthrow of Saddam did?

Yet, within Australia, there’s almost no discussion of what the mission’s supposed to deliver to the people of Iraq and Syria. We’re keen to punish the Islamic State – and if that punishment makes matter worse, we’ll retreat back to our wealth and safety, and let other people deal with the mess.

But that’s only part of the story.

For, if the propensity to panic reflects Australian prosperity, it’s also perhaps indicative of something else: a lack of confidence by Australian politicians in their ability to govern.

In a different era, leaders might have demonstrated their leadership through their ability to dampen fears arising from a terrorist incident. They might even have judged the ease with which they provided that reassurance as a measure of their own political authority, on the basis that a confident politician ought to be able to prevent a nation of 20 million succumbing to fright over a single teenager with a knife.

Yes, in a different era – but not in ours.

Today, politicians react in an entirely different manner, almost as if leadership consisted of putting themselves giddily at the head of the hysteria, rather than seeking to quell it. Hence, over the past weeks, we’ve seen parliamentarians and pundits competing with each other to talk up (rather than minimise) the threat posed by the Islamic State, with increasingly wild, almost deranged rhetoric.

What’s going on?

We’re living through a massive disengagement from traditional politics. A recent study showed that only 43 per cent of people believe it matters which party is in government, a decline of nearly 25 per cent over the past seven years.

In that context, fostering an over-the-top fear about terrorism provides a way for politicians to reach, even if only temporarily, their constituents. You might, to take a wild example, be presiding over a rudderless government, struggling to sell an unpopular budget. You have no particular solutions to the discontents of the voters – but, in the wake of a terror attack, you can empathise with their fears, and position yourself as doing whatever it takes to keep your people safe.

It’s smoke and mirrors, of course: a simulacra of strength rather than strength itself. Again, old-fashioned leadership would have entailed talking down the threat, confident that, when the panic died away, the public would remember which leaders remained calm.

By contrast, Abbott might get a brief poll bounce from presenting himself as tough on terror, but the long-term result will be the exacerbation of the popular alienation from politics as a whole, as voters lose interest in the bipartisan obsession with policies that bear no relationship to their actual lives.

Think of the new laws threatening journalists with 10 years jail for reporting on ASIO operations. Despite all the wild allegations surrounding Omarjan Azari and Numan Haider, no-one – no-one at all – has suggested that reporters and whistleblowers have jeopardised the public.

There has been precisely zero evidence of the ills the new laws will overcome. Yet legislation implementing draconian restrictions on media freedom can get immediate bipartisan support, even as the parties struggle to offer ordinary people improvements for health, education and other basic services.

These are strange times – and they’re set to get stranger. Last week, we learned that Scott Morrison was tipped to take on new responsibilities for counter- terrorism.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man, as they say.

Morrison’s fortunes have risen because of his perceived effectiveness in stopping refugees reaching Australia by boat. Like the threat of terrorism, the tiny number of asylum seekers coming to Australia is essentially a non-problem escalated into an existential threat by self-serving politicians.

Morrison’s willingness to make others suffer in order to present a ‘solution’ to the refugee issue does not bode well in terms of future discussions of national security.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.