SPECIAL INVESTIGATION: At the start of the pandemic, international jetsetters were rushing home to quarantine in five-star hotels at Australian taxpayers’ expense. And complaining about it. At the same time, governments around the country were ‘ring-fencing the vulnerable’ by blocking access to aged care centres, and closing remote Aboriginal communities. Meanwhile in Wilcannia, a chronically overcrowded Aboriginal community in a remote corner of the Far West of NSW, residents there couldn’t even convince the Berejiklian government to give them tents so they could isolate from the virus in their own backyards. Now, 18 months after the COVID-19 crisis began, more than one third of the community has contracted the disease in a shocking outbreak that has captured the world’s attention. Chris Graham, Cherie von Horchner and Jack Marx report*.

The NSW Government didn’t just ignore pleas from the Wilcannia community to address chronic overcrowding at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic; on multiple occasions bureaucrats aggressively dismissed basic solutions put forward by community members, refusing requests to lock the town down before the virus arrived and telling them overcrowding in Wilcannia was a problem “before the COVID-19 outbreak and will be here well after”.

The rebuffs came from state government bureaucrats based in the region, but also from some of the most senior disaster preparedness experts in the state, including the NSW Health Department’s ‘District Disaster Manager’ for the Far West region of NSW, and a Deputy Police Commissioner who has served as the ‘State Emergency Operations Controller’ since the pandemic began.

In desperation, local Aboriginal leaders approached the Central Darling Shire Council and formally requested emergency funding to purchase tents, so that Wilcannia residents could isolate in their own backyards if and when the virus arrived.

The request met a hostile reception from senior bureaucrats within the Department of Health and the Department of Family and Community Services, before

the issue of overcrowding was ultimately removed from the weekly agenda of the Local Emergency Management Committee, the body charged with keeping residents safe during the pandemic.

Just over a year later, in August 2021, the SARS-COV-2 virus hit Wilcannia, spreading to more than 10 percent of the community in less than a week. Forced to fend for themselves in the initial stages of the outbreak, some residents ended up isolating in tents in their yards, which were donated to the community by an Aboriginal organisation after the government’s refusal.

Today, less than two months after the outbreak began, 151 people – almost 40 per cent of Wilcannia’s Aboriginal population – has now been infected, making the transmission rate by far the worst in the country.

The revelations are contained in leaked minutes from Local Emergency Management Committee (LEMC) meetings staged from March to June 2020, copies of which have been obtained by New Matilda.

LEMC’s exist in all NSW towns, and are convened by local councils in the event of an emergency. All relevant government departments participate in the LEMC meetings, which can occur monthly, weekly or even daily, depending on the scale of the crisis, and may also include local non-government organisations and community representatives.

The minutes from the Central Darling Shire Council LEMC meetings in March, April and May 2020 reveal that as governments around the country moved quickly to prevent access to aged care centres and remote Aboriginal communities – in Cherbourg, Queensland, for example, police and Army blocked anyone but essential workers entering for months – the NSW Government was refusing special measures for its own Indigenous population, with state bureaucrats at times indifferent to local Aboriginal concerns around the pandemic, but also occasionally openly hostile to their proposed solutions.

The LEMC minutes also make clear the NSW Government was well aware of the overcrowding problem in Wilcannia long before the outbreak that crippled the community last month. It’s a problem that’s existed in the community for decades, and officials knew self-isolation in the event of an outbreak would be virtually impossible. Yet despite this, the community was repeatedly told overcrowding was “not the issue”, and requests from the community for help were aggressively rejected.

The LEMC minutes also reveal that before the virus arrived, the NSW Government refused repeated community requests to prevent through traffic on the Barrier Highway from stopping in Wilcannia, with senior NSW police advising the LEMC that a “lockout” of passing traffic was “not on”.

But once the community was infected, roadblocks were thrown up on the Barrier Highway and the community was locked down into overcrowded housing, virtually guaranteeing the virus would spread quickly and widely. Like Cherbourg in Queensland, Wilcannia finally got additional police, and the Australian Army, but they weren’t sent in to keep people out – they were tasked with ensuring “compliance” by the Aboriginal population.

That compliance measure was, and remains, targeted solely at Wilcannia’s Aboriginal residents. While Aboriginal people make up about 70 percent of the local population, 100 percent of confirmed COVID-19 patients in the town are Indigenous.

What the minutes say

On March 30, the LEMC minutes record the first recognition from the NSW Government that it knew overcrowding in Wilcannia was – and remains – a problem.

“Denise McCallum reported that 7 Rooms available for self-isolation at the Wilcannia hospital (LOW RISK) Transfer to Broken Hill for Moderate/Severe Risk 10 Bed ward ready. Self-isolation still an issue, available accommodation in regions being investigated e.g. motels, hotels, teacher housing, police barracks.”

Denise McCallum is a senior NSW Health executive within the Far West Local Health District (FWLHD). She serves as General Manager District & Remote Health Services. The same minutes also record:

“Brendan Hedge (sic) is collating all information and already has started on a list of available Accommodation”.

“Brendan Hedge” is Brendan Hedger, the most experienced bureaucrat in the Far West in charge of disaster planning and relief, having served in the role for almost two decades. On April 14, 2020 Mr Hedger would feature more prominently in the minutes, after the General Manager of the Central Darling Shire, Greg Hill, tried to lobby the LEMC for exactly the sorts of protections that were being rolled out in towns and aged care centres across the nation – isolated accommodation for community members most at risk from the virus.

“Greg Hill: – Asked if those that are highly vulnerable could be placed in accommodate (sic) for isolation.

“Brendan Hedger: – replied No! where would you stop please note this decision is not dollar driven but resources driven”.

Two weeks later, Mr Hill once again raised the issue of alternative accommodation, after representations from local Aboriginal leaders. And once again he was shot down. On April 27, the minutes of the LEMC meeting record this exchange:

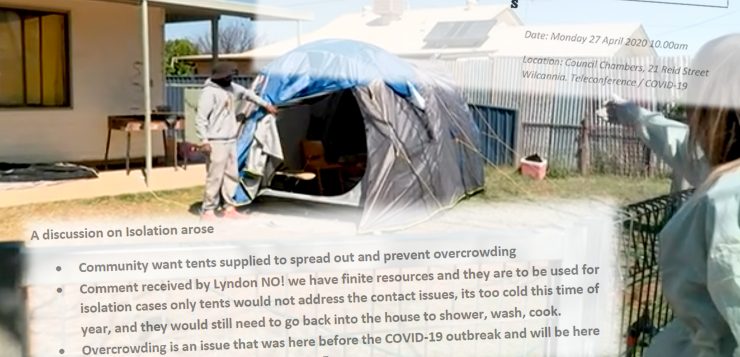

“A discussion on Isolation arose Community want tents supplied to spread out and prevent overcrowding. Comment received by Lyndon NO! we have finite resources and they are to be used for isolation cases only tents would not address the contact issues, its (sic) too cold this time of year, and they would still need to go back into the house to shower, wash, cook.”

‘Lyndon’ is Lyndon Gray from the NSW Department of Family and Community Services. New Matilda sought comment from FACS about why Mr Gray – a bureaucrat who works in housing – was advising an emergency management committee about transmission of a virus. No response was received at the time of press. To underscore Mr Gray’s view, the minutes note:

“Overcrowding is an issue that was here before the COVID-19 outbreak and will be here well after, solving 1 problem will create 5 more.”

In desperation, local elected leaders Monica Kerwin and Michael Kennedy formally sought emergency funding from the Central Darling Shire to purchase tents, so that community members could at least isolate in their own backyards, or ‘go bush’ if the virus arrived.

Mr Hill took the formal request to the next LEMC meeting on May 4, to seek the views of state government officials. The response he drew was even more hostile than the previous weeks.

“Greg Hill wishes for input concerning application for funding request being for $10 thousand dollars to supply Wilcannia locals whom have overcrowding issues with Tents and sleeping bags.

Jenny Twaites [General Manager of the Wilcannia Local Aboriginal Land Council] commented it would be much appreciated [and]will cover the overcrowding issue.

Lyndon Gray replied it is not our role to tell Council what to do, this is not the place for this discussion and with the cold months coming up he feels it is not a good idea.

Jenny Twaites [said]it will help those sleeping on verandas.

Craig Oxford responded COVID-19 is the issue here not overcrowding

Tony stated that it is taken on board.

Greg asked for assistance as he was wondering if there would be ramifications for other agencies. Denise McCallum offered to let Brendon Hedger know of the issue and have him call Greg Hill to discuss.

Anthony Moodie requested that the issue be removed from the meeting. Greg Hill did not agree and read out the e-mail request, Anthony Moodie would offer no comment.”

At the time, Craig Oxford was the most senior health bureaucrat based in Wilcannia, and Anthony Moodie was the Inspector in Charge at Wilcannia Police Station (both men have since left the community). A spokesperson for NSW Police told New Matilda:

“On Monday 4 May 2020, Central Darling Shire Council Local Emergency Management Committee held a meeting regarding preparedness for COVID-19. Before the meeting, a member of the community submitted an item for the agenda. The item proposed discussions regarding an application they had made to Council for funding to buy tents and sleeping bags, to assist the Wilcannia community with overcrowding.

“As the application was a matter for Council and outside the

scope of that immediate LEMC meeting, Insp Moodie requested the item be

discussed directly with Council.”

Ultimately, the community’s attempts to get emergency government funding for tents were defeated. Instead, sleeping bags and tents were donated to Ms Kerwin by the Murdi Paaki Regional Assembly, the peak Indigenous political body for the west and far west of NSW, headquartered hundreds of kilometres away in Cobar. They would come in handy a year later.

The virus hits

When the outbreak began in mid-August, community members were forced to isolate in the tents when it became clear the FWLHD wasn’t prepared for the rapid spread of the virus in overcrowded housing.

“I had the tents in storage,” Ms Kerwin said. “When COVID hit, I was thinking, ‘Oh my goodness, what do I do?’”

They were quickly distributed throughout the community, but it wasn’t enough to prevent widespread transmission, with Ms Kerwin noting that one of the people who fought hardest for the community at the start of the pandemic – Michael ‘Cassidy’ Kennedy from the Wilcannia Local Aboriginal Land Council – was one of the first to be struck down.

“The first people that got [COVID] it was Cassidy himself, and his little family. The man was standing up for us to avoid getting COVID, and he was one of the first to get it, him and his wife and two daughters.”

As Chair of the Wilcannia Working Party, Ms Kerwin served on the Local Emergency Management Committee in the early days of the pandemic. She said she eventually walked away in frustration at what she says was a lack of concern from some NSW Government officials, and a refusal to act on even basic requests.

“The community was the problem, not COVID. That’s how we felt, that we were the issue,” Ms Kerwin said.

“Every time I sat in a meeting I said, ‘We need to tackle the overcrowding situation’. We were just trying to isolate people from a virus, but they were more or less going around saying, ‘Here they go, asking for things again.’”

The minutes of the LEMC meetings also record Ms Kerwin supporting a lockdown of Wilcannia. On March 30, 2020, she voiced her support for a lockdown, along with Jenny Thwaites from the Wilcannia Local Aboriginal Land Council, and Bob Stewart, the administrator of the Central Darling Shire Council. That lockdown only happened once the virus arrived 18 months later.

“The community had a meeting in the park, and we decided we needed to come up with a plan to lock Wilcannia down now, to put up roadblocks,

to shut up the toilet facilities, to tell tourists to pass through Wilcannia and not stop and get food and fuel,” Ms Kerwin said.

“We were told they needed to keep traffic flowing. To [the NSW Government]it was just another Aboriginal community. It was just Wilcannia.”

The LEMC minutes from April 14, 2020 note:

“Andrew Spliet: – Lockout not on given discussion thus far, roads must stay open, signage can be used to advise no-one from the area may stop/stay in line with current health orders. Deputy SEOCON, Gary Worboys stated that they don’t believe a lockdown will work.”

Andrew Spliet is the most senior police officer in the region – the Superintendent in charge of the Barrier Police District. Gary Worboys is even more senior – he’s a Deputy Commissioner and the State Emergency Operations Controller (SEOCON), based in Sydney.

Ms Kerwin says once the virus arrived, lockdown was the first thing the NSW Government did, sending in additional police and soldiers from the Australian Army.

“They wouldn’t lock Wilcannia down last year to keep the virus out, but once it was here they lock us down in overcrowded housing,” she said.

“The extra police and Army were only sent here for compliance. They weren’t sent here to support anything – they were sent here literally to enforce the law.

“Whenever the police went to a household to do a compliance check, you had the Army standing there waiting for anything to happen with the household. It was very intimidating for a lot of community members to have two police and four army men standing at their front door or gate.”

Ms Kerwin also slammed the eventual response to overcrowding by NSW Health – 30 motorhomes, which arrived in the community a fortnight ago.

“It took nearly a month before the vans arrived. It was too little, too late,” she said. “We told them if COVID hits Wilcannia and an Aboriginal person gets it, we know the Aboriginal community – we’re Aboriginal. We know who we socialise with, and we knew it was going to be the way it is now.

“At the end of the day, the biggest threat to the community was [institutionalised]racism, not a virus. And it still is to this very day. We’re still facing that today.”

The Far West Local Health District declined to answer specific questions from New Matilda, including questions directly specifically at the CEO Umit Agis, and at health officials Craig Oxford and Brendan Hedger. However New Matilda was advised that Mr Oxford is no longer working for the NSW Department of Health, and Mr Hedger is on extended leave.

The Department of Family and Community Services has also not responded to detailed questions about bureaucrat Lyndon Gray’s involvement in the LEMC meetings at the time of press.

* This story is part of an ongoing investigation series by New Matilda called ‘#MeanwhileInWilcannia’. New Matilda is an independent publication. You can support our work by subscribing here, or sending a one-off contribution via Paypal here. We’re partnering with the Barrier Truth, an independent newspaper based in Broken Hill in Far West NSW, for some of the reporting.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.