Ladies and gentlemen, welcome to the Apocalypse. It’s going to be a wild ride, so please fasten your seatbelts, keep your arms inside the guard rails, follow instructions from your crew, and we’ll have you back at the Visitor Centre in time for lunch. Or not. Depending on a couple of things. Your choice. Your guide for today is Mike Dowson.

If, tomorrow, Earth was struck by an asteroid, like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago, what do you think would happen?

You know what would happen. Of course you do. The world you know would be swept away.

Your insurance, your investments, your professional network, none of that would help you. Fund managers and film stars would defer to nurses, mechanics and security guards. Many of the things which give us status and protection in this artificial realm would be useless.

But some things would matter more than ever. A place to sleep. A hand to hold. The safety of the group. The rule of law.

If you survived the impact, the blast, the fires, the toxic clouds and acid rains, any chance of a benign future would depend on a few human evolutionary adaptations. You would see quite starkly, then, the importance of our extraordinary ability to cooperate, organise, take care of one another and solve problems together.

It really isn’t any different right now. Look around you. How much of your life did you invent for yourself? Your knowledge, skills, and almost every comfort and convenience you enjoy were bestowed by others. You may say you ‘earned’ them. But others made them possible. The only difference is we presently have the luxury of taking them for granted.

But we don’t need to wait until tomorrow. The asteroid has already struck. Species are disappearing, just as they did at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Deadly contaminants are spreading. The pillars of our familiar biosphere are collapsing.

We can’t see the asteroid clearly because it’s so diffuse, and its full impact is registering more slowly than a human lifetime. We can’t see the asteroid because it’s us.

The mild Holocene, in which humans spread across the globe, is over. The evidence that we have caused this change is overwhelming. But to argue about it is pointless now. The fact of it is everywhere apparent. The Murray-Darling basin is drying out. The Great Barrier Reef is dying. The Australian bushfire season starts in winter.

And yet, publicly, climate change has remained a niche topic. Its intermittent newsworthiness has derived from lingering controversy. Is it real? Is it human-induced? The media love stories about farmers battling drought, and helicopters hoisting flood victims to safety. But in a news bulletin full of “natural disasters”, climate change has usually been conspicuous by its absence.

We have acted like doomed sauropods, blithely munching on cycads, while shockwaves of destruction race toward us, tearing holes in the systems on which we depend, with only an eerie glow on our horizon to tell us an age has passed.

Aren’t we smarter than this? What the hell is science for, if not to see beyond the range of ordinary senses? And hasn’t science already warned us? Why don’t we do something? What’s wrong with us?

Perhaps that’s the wrong question.

Who Benefits from Inaction?

Surveys show a big majority of Australians want action on climate change. If you only listened to our governments and media, you’d assume we want coal power, high immigration, low wage jobs, lower taxes and fewer social services. But none of those aims is supported by the survey data. Somebody obviously wants those things. If it’s not us, who is it?

The survey questions, like the pronouncements of public figures – indeed almost every public communication on the subject – are built around an implicit message – that the environment and the economy are at odds. Similarly, it’s assumed that human security – wages, affordable housing, pensions and benefits – can only be improved if the economy improves.

What kind of economy takes precedence over people and the planet we live on?

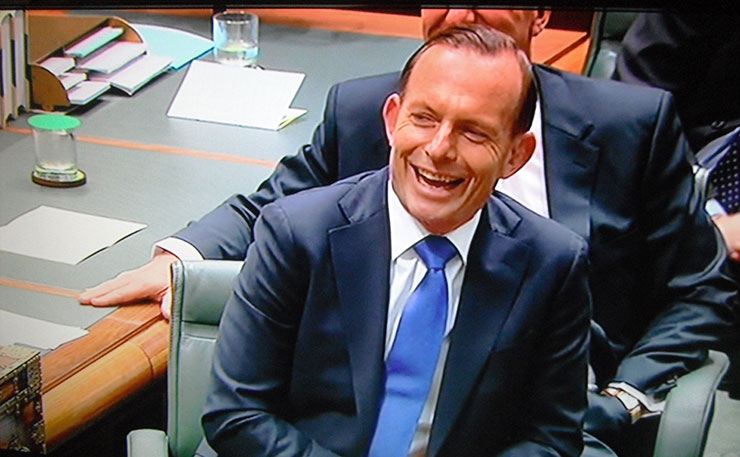

Former PM Tony Abbott likened climate action to appeasing volcano gods. This is deeply ironic. Climate action is based on science, not on superstition. Yet the simile is apposite for the way our politicians worship the economy.

There’s a body of contemporary research which helps explain why civilisations fail. We can have a healthy environment, a healthy society and a healthy economy, or we can have none of them. But one without the others is only sustainable if humans leave the scene.

Many economists will tell you it’s not the economy which is incompatible with our other needs, it’s our economy. Dominant industries like fossil fuel, which serves present energy requirements at the expense of a liveable future; our monstrous, parasitic financial services industry, which feeds on indiscriminate GDP growth; and our powerful construction lobby, demanding population increase to house and transport from rezoning windfalls and the public purse; all magnify an apparently insoluble dilemma.

Don’t these people care about climate change? Don’t they worry about their children and grandchildren?

No doubt they do. Sales of NZ South Island refuges, cold war bunker conversions, and designs for colonies on Mars indicate that even the global superrich take the threat seriously. But it seems they propose to deal with it in isolation, leaving the rest of us to our fate.

What about the rest of us, then? If it’s just a few sociopaths dragging us all to the brink of extinction, why don’t we stop them?

It turns out the conspiracy is broader than we imagined. Some of us are in on it too.

The Absentminded Conspiracy

Suppose the asteroid doesn’t wipe away your world tomorrow. Are you one of the millions who will burn carbon for hours through dense traffic or ride a packed commuter train to an airconditioned workplace?

What will you do there? Is it really so important? Or are you one of the many workers historian Rutger Bregman speaks with, who believe their jobs are essentially pointless? People who toil for years on tasks which apparently serve only to keep others in dense traffic and airconditioned workplaces.

And to what end? Just to live another day? So we can shackle ourselves to the towering mortgages we create by cramming ever more of us into already crowded cities?

The visionary systems thinker David Fleming wrote eloquently about the ‘intermediate economy’. It doesn’t directly satisfy human needs. As population grows and trade expands, it provides the machinery to coordinate producers and consumers at a distance. If left unchecked, it tends to become self-serving. In the rise and fall of civilisations, this doesn’t augur well.

As supply and demand become dependent on the intermediate economy, it can ask more for its services. Over time, status and income decline for the people who grow food, build houses and educate children. Instead, wealth accrues to professions like finance, corporate law, marketing and management, which keep the machinery in motion.

Soon, much of what these enterprises do is what business academic Adair Turner calls “zero sum”. They’re not helping to grow the pie anymore. They’re using their power and position to claim a bigger share of the existing one. Corporations, government departments and hegemonic unions impose rents and tariffs and shirk accountability for no better reason than they can.

As this diversion of wealth marginalises productive citizens, new organisations emerge to pick up the pieces. Charities provide food, shelter, support and counselling. Clever start-ups mobilise impoverished workers to use spare hours delivering low cost services to their cash-strapped peers.

Eventually, these entities form symbiotic relationships. Corporations fund election campaigns and boost their brands with sponsorship. Governments dismantle regulation and provide subsidies and tax incentives. Charities collect an informal goodwill tax to augment dwindling social equity. Agencies set up to serve, and staffed by people with mostly good intentions, cooperate to harvest residual value from the lives of those who produce essential goods and services.

People raised in such a system are apt to share its morals. They may applaud rent-seekers for their initiative. If they prosper by making gambling more addictive or finding loopholes to deny disaster victims their insurance payouts, what matters is that they work hard, achieve their targets and make shrewd investment decisions with their earnings.

Political acumen becomes more important to success than meaningful competence. Without family money, fortuitous connections or elite credentials, people struggle to secure a foothold on the ladder at all. Others fall off when they get sick, bear children, lose a partner, or their industry is disrupted. Wealth is concentrated, and reduced spending power among the less advantaged reinforces a downward spiral of demand in the productive economy. Talented, educated people join the unemployed or working poor.

Like an algal bloom in a river, when the intermediate economy becomes “too big to fail”, it begins to suffocate and poison the host system. Its pervasiveness defies corrective action. From Sumer to the Kmer, we can detect how variants of this pattern have inhibited adaptation in stratified, settled societies, presaging collapse, often triggered by climate change.

Have you noticed what happens in the city during the Easter holidays? A large proportion of the population is missing. But the trains run, and the shelves are stocked. In fact, it works better. The queues are shorter, the traffic thinner, and fewer emails clog your inbox.

Here’s a little thought experiment. What if we paid these people to stay at home? What disaster would befall us? More parents spending time with children? Fewer traffic accidents? People swapping soulless occupations for doing what they love?

Perhaps we’d also have fewer overworked people succumbing to drugs, alcohol and suicide; fewer emergency responders suffering trauma; and fewer health workers struggling to put them all back together.

In the way we measure our economy, these aren’t problems at all. They add to ‘jobs and growth’. And that’s the way most of us secure our future. Who doesn’t want a liveable planet for our kids, just as we want more time with them, and more affordable housing when they grow up. But nobody wants his job to be the one that disappears, or her house the one that devalues.

Climate change might get us in the end. Our more pressing concern is getting left behind. We are clinging to a ledge above a precipice, with whatever protection employment and home ownership can provide, harried by sharp-taloned special interests lacerating every lifeline offered to us.

What can be done?

A Way Out of Purgatory

There’s a clue to be found in the social democracies of northern Europe. They have most of the challenges we have, plus some of their own, but they also did a few things differently and we can learn from the results.

They didn’t just throw open their doors to global market forces. And they didn’t mothball their regulators. On the contrary, they introduced citizen representation on boards and quotas for female participation. And they strengthened their commitment to democratic processes and public services.

Citizens who are secure are more amenable to necessary change. Consequently, these countries were able to reduce working hours, promote cycling and social housing, restrict motorised access to cities and switch to renewable energy sources. Now they lead the developed world in sustainability, in addition to wellbeing and social justice.

Kate Raworth’s famous doughnut model for the economy expands on this principle. Imagine a doughnut. It’s round, like a planet, with a hole in the middle. The outer boundary of the doughnut represents the limit of sustainable consumption. The boundary around the hole represents the minimum requirement for human wellbeing.

The idea is to keep everyone within those boundaries. It ought to be common sense. But history tells us societies don’t remain peaceful and prosperous if they destroy their habitat or let their people fall into destitution. They may suffer decline or start wars to forestall it. But I can find no examples of societies which broke these rules and simply flourished.

In Australia, we are flouting both rules. Carbon emissions and poverty are increasing simultaneously. We are not presently a country which is equipped to deal with serious problems of any kind. In the long Indian summer of our post-war boom, greed, cunning and malice flourished in the shadows of weak accountability. A recent string of exposés and public inquiries, with more to come, points to a pattern. We have become a playground for opportunistic thieves – shallow, venal hustlers who steal our national prosperity while no one is looking.

It took decades to get into this mess. So we can hardly expect a quick fix. Before we can do much about climate change, and all the related disasters that are stalking us, including biodiversity loss, soil degradation, water shortage, pests, pathogens and pollutants, we need to fix the systemic causes of our collective paralysis. Then we may be able to achieve the consensus we need for the truly epochal challenges to our future prosperity.

In a forthcoming series of articles*, I will build a case for how this might work.

* This is the first in a series of four articles from Mike Dowson on charting a more responsible future.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.