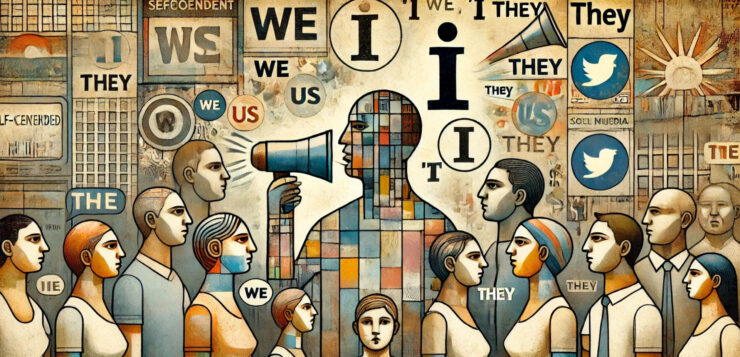

Forget GenX or GenY, or any of the other monikers associated with generational identity. We’re actually living in the ‘Me Generation’. Mark Furlong explains.

A mechanic regularly inspects the old lift in our building. Last month I found myself enjoyably chatting with a new, very sociable technician. We spoke in a fun way for some time before I asked if he had any ideas how we might fix a persistent problem – the lift door sometimes suddenly closes immediately after it has opened. He reflected for a moment and then said I don’t know. I wasn’t here when the old girl was installed.

A few weeks later I heard two statecments on the same day that reminded me of this non-sequitur. The first occurred in a café when, on entering the restaurant, I asked a waiter if I could do a deal to bring in a bottle of wine. The response was: I’m sorry. I do not have a licence for bring-your-own. Earlier that day I had visited a bakery in the afternoon and asked if they were any buns left. The reply took the same form: I only have savoury things. Pies and sausage rolls and other not-sweet items.

Both examples baited an obvious retort: It’s not about you. You represent, rather than you are, or own, the business.

On the same day The Guardian published a piece titled Heroically, I wrote a will. But what if I’d hate my own funeral? (Emily Mulligan, 23.08.24). Stiff, I said to myself, you are not the centre of the world, and that is especially true once you’ve gone. The funeral is not for your benefit. What about thinking about the people you say you care about?

More generally, one hears me-centred statements in a great number of places. For example, when a witness is asked to describe an adverse event, such as a flood, what is said to the reporter is likely to be an iteration of I’ve lived here for six years and I’ve never seen anything like this before rather than be given a description the listener can scale.

The following examples bond the hilarious with the horrifying. In the presence of an abstract question – say, What’s your view on the Russian Revolution? – it is not unusual to hear even university-educated types say something like I don’t know. I wasn’t there. Worse happens if the question is What do you think of the riots in Greece? and the reply is an indignant How should I know!? It’s got nothing to do with me. Self-referential, yes, and concrete too. To re-cycle de Montaigne’s telling phrase, its down the spiral staircase of the self.

We are in the middle of an epidemic whose primary symptom is putting the i up-front. This plague has afflicted nearly every one of us, if not as a carrier then as someone who is impacted by the spread of this malady. For the infected host, the i-ascendant approaches the autonomic.

Fashionable examples of i-speak have become so familiar as to seem natural. For example, it is now expected that essayists and book reviewers, feature writers and commentators, will insert themselves, mostly right at the outset, into the accounts they author (as was seen in the above first paragraph).

Of course, first-person expression is not new; it has long been the voice of memoir, of travel writers, and of everyday conversation, mindful that codes of humility and other-orientedness previously constrained its application. More recently, several movements have given the i-statement a legitimacy, and a glamour, that has disrupted these restraints. Pioneered by the personal is the political slogan championed by 1970s feminism, and also by the verve of the New Journalism first identified with Tom Wolfe and Hunter S. Thompson, first person accounts have come to have a less contingent, more honoured place. This prestige is based on the same premise that now grants those with the ‘lived experience’ – of indigeneity, disability, gender diversity, etc. – genuine status.

There is much that is progressive in this transformation. The period when one was expected to obey the voice that said ‘you must’, ‘it is established that’ or ‘the findings are clear’ have passed. Reflecting on, and perhaps challenging, the third person accounts issued by this or that authority is not only tenable but is now obligatory. Messages delivered with impersonal authority should no longer be uncritically consumed. Power and privilege have long been disguised by the experts and authority figures who use the voice of pseudo-objectivity in their pronouncements.

What then of the status of the alternative – what is the value of first-person speech and personal experience? Historically, first-person accounts, like personal experience, at best have been seen to have little currency in assessing claims to truth. Not only viewed sceptically, in much philosophy of science it was understood that personal expression was antithetical to real knowledge: it was assumed that what you think you know clouds rather than informs true understanding. More recent thinking has come to accept that what you or I say is real, valid and important is real data that should be held up as a serious epistemological resource. Rather than actively denigrated, this resource needs to be valued.

This value should be genuinely celebrated, mindful we do not lurch from rejecting third person accounts to eulogizing lived experience. As well as being sceptical of received expertise, it is also necessary to acknowledge that lived experience is always partial. It would be throwing the baby out with the bathwater to universalize the validity of this or that individual’s, or this of that group’s, opinions, emotions or memories. As a kind of argument by assertion ‘my experience is X’ offers a good starting point, but one’s experience does not guarantee a generic truth or warrant a claim to universality. Personal experience does offer real data that feeds into, but should not be understood to form the limiting boundary of, the sources that builds a fit-for-purpose knowledge set.

The above offer context, but a visceral driver is behind the ascension of the i-statement: the rise in this form of expression has a purposive use-value. Subjectively, I get a pick-me-up, a sugar hit, a swelling of the chest, in pushing myself forward. More situationally, in the hurly-burly of social exchange putting the i-me-my-mine up-front auto-inflates the speaker’s centrality. Hey, its moi who is at centre stage. This practice exercises agency in the service of warding off feelings of inferiority, of invisibility, of irrelevance. Once this intoxicant has been enjoyed, once the hit becomes something that can be missed, there is a habit that is hard to kick. And one has an alibi, a mind game that each addict masters, to rationalize continuity. I won’t be intimidated. I can’t allow myself to be pushed around. I won’t back down. Why not! One more for the road sounds good.

Other disadvantages need be entered in the ledger that documents self-promotion. Not least of these is that if making i-statements becomes the generic de fault there is a collective flight from the abstract. More than a harmless, involuntary tic demanded by fashion, relying on the i-statement represents a regression towards mindlessness. Retreating to saying ‘I wasn’t there’ or ‘my experience is’ represents something deeper than fashionably re-cycling a chunk of idiom.

If the interest is to regard the ascension of the i-statement as an epi-phenomenon – as a sign of something deeper – the most pressing candidate for attention is what Zygmunt Bauman termed the process of individualization. Much like Ulrich Beck and Anthony Giddens, Bauman says this process is centred on the down-loading to, and the floundering of, the individual who has been delegated total responsibility for all their life choices. This idea offers a frame for theorizing the linguistic regression that is seen in falling back on the unreflective and concrete i-me-my-mine. Retreating to this lonely spot absolves one from being aware of a context that insists on one’s irreversible responsibility.

If all this seems too heady, one might keep to the view that the reign of the i-statement is no more than a fashion. Perhaps it is no more serious than what happens when an item of slang takes hold and is disseminated into the wider society as we saw in the word ‘cool’ moving from the margin to the mainstream. Another possibility is more weighty. Perhaps, the triumph of the i-statement approximates a neural event. We are told our hardware is plastic, so it might be we being re-wired. However thought about, the concreting of the i has a pragmatic effect. This practice tightly draws the horizon of a personal awareness to that which is i-referenced.

Of course, all pronouns have a politics. One sees another example in the many instances of official and commercial misspeaking that are now so pervasive: your IT provider writes to say we are updating our terms of service. Seeking to avoid appearing impersonal, as a machine that is intent on gauging its valued customers, the deliberate use of the terms us, our and we is designed to summon trust and a sense of the collective. This contrivance is duplicitous. It is a form of address that seeks to con. There is no real we that wants to say sorry when a bank officially apologizes, when you read we are excited to offer product X or, that we at business B are here to help. As is the case with sensitively using the pronouns us and them, it is best to be careful in using, and listening to, every instance of i and we.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.