Turns out ‘Making America Great Again’ is a bit more complicated than some expected. That might have something to do with long-term greed and an economy heavily reliant on debt, and endless growth. But that’s just one of the intractable symptoms. An emerging problem is major world economies like Russia, China and Iran restructuring and ‘dumping the dollar’. Rita Bodrina explains the brave new economic world that is just starting to peak its head over the horizon.

The global financial landscape is undergoing a dramatic transformation, driven by a powerful force: dedollarisation.

This shift away from 80 years of US dollar dominance signifies a fracturing of the once monolithic, American-controlled financial system. This fragmentation, fuelled by sanctions, trade wars, and a changing role for international financial institutions, marks the dawning of a new economic order.

Paper Soldiers

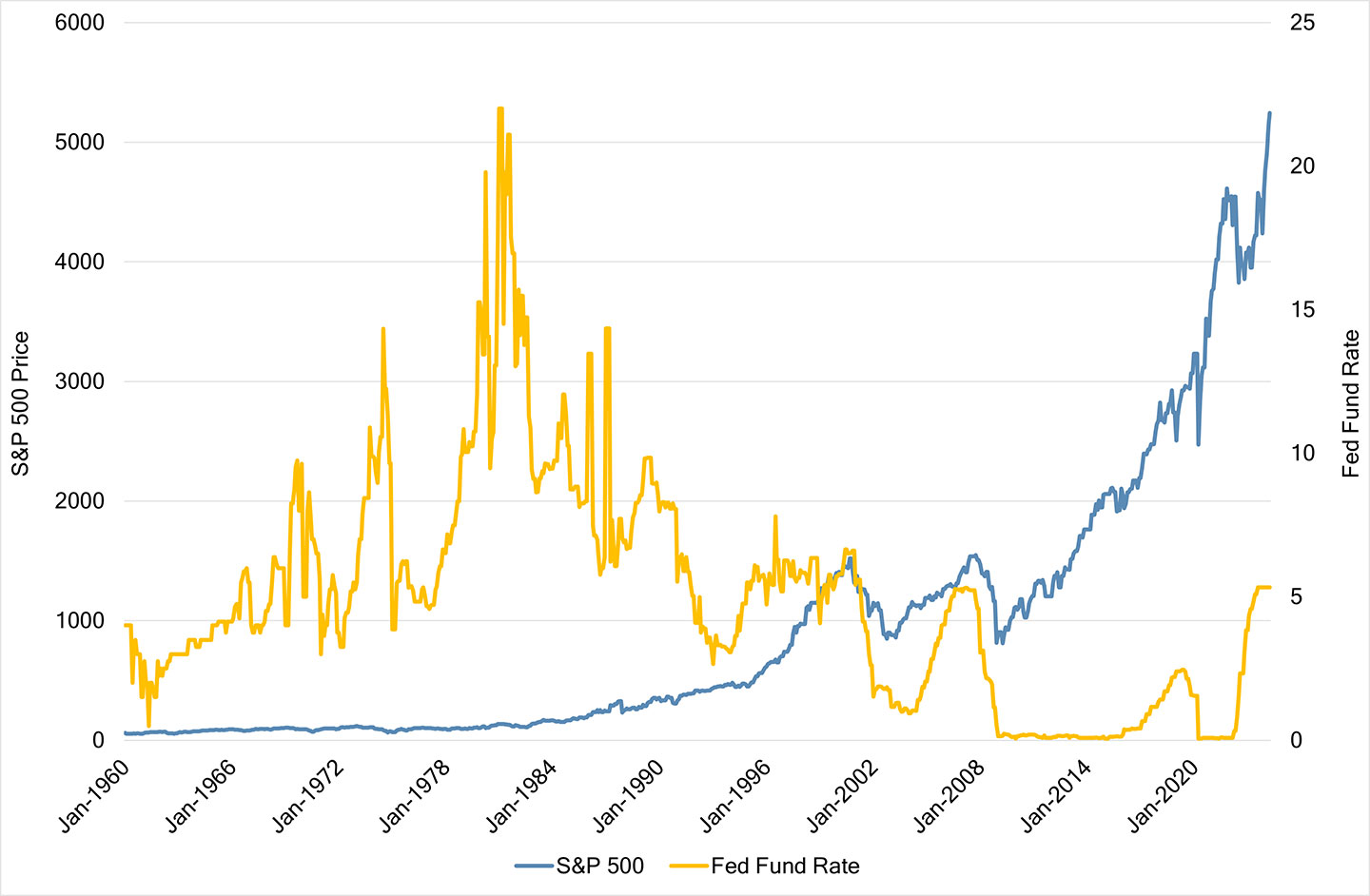

Before the early 1980s, economic growth was driven by the ‘real economy’. Financial indicators like credit growth and asset prices moved in tandem with these fundamentals. In other words, the dog wagged the tail.

Think of the ‘real economy’ like this: it’s the part of the economy that is focused on making and trading real (tangible) things, like food, clothes, houses and cars, rather than just dealing with money and financial transactions.

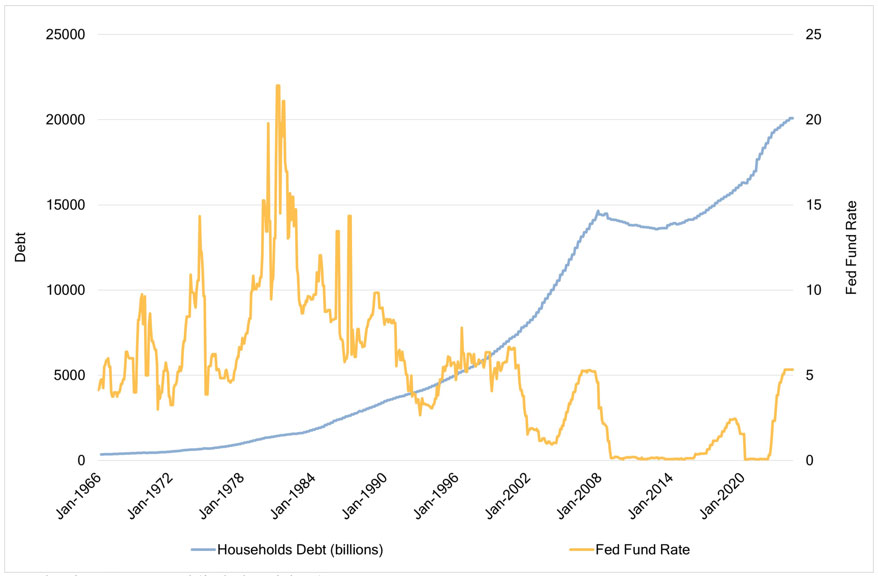

However, post-1980s, the economy became heavily reliant on credit as the primary tool for growth. The theoretical aim was to drive economic expansion by any means necessary: reducing interest rates to make money cheaper and cheaper.

By pushing rates down, the government enticed people into the economy to speculate and spend. If holding onto your cash doesn’t make you very much, or at least less than it did yesterday, and borrowing costs comparatively little, then you’re enticed into the economic ‘casino’ to spend your debt-chips.

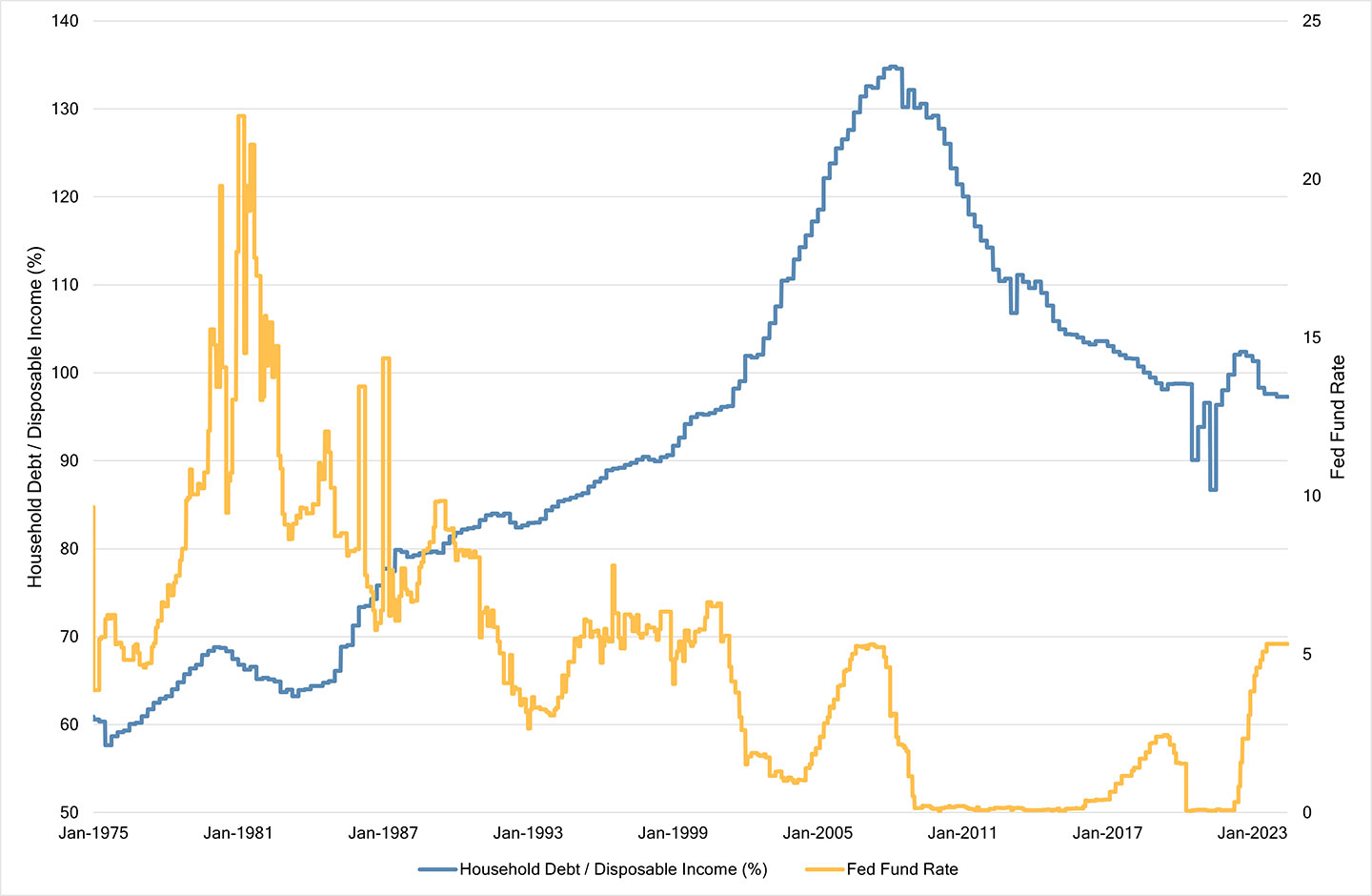

‘You could always refinance’ became the slogan for decades, up until only recently when we hit the bottom and interest rates had nowhere left to go, except up (or negative, if you’re Japan).

In practice, this worked as follows: You go to the bank and take out a loan to buy, say, a car with repayments of $1,000 a year. Twelve months later, the banker informs you that interest rates have dropped, so you refinance at a lower rate. Now, you only need to pay $800 a year, or you can keep paying $1,000 and top up your loan with a bit of extra spending money that you can use to upgrade the fridge you’ve been wanting. You use this extra money to buy something else, effectively having more money at the same price! In this scenario two things remain true: interest rates keep falling and your debt keeps rising.

This cycle repeats, and each time you leave the bank with fuller pockets but without a corresponding increase in your own repayments. Eventually, having amassed a mountain of debt, you return to the bank, but find that interest rates haven’t gone down this year… they’ve gone up. “Oh, crap!”

The description above highlights how we got an artificial boost in credit that lead to what is now called the “new economy”. This economy is characterised by assets with outrageously inflated values detached from any real-world metric (think Australia’s housing market). As a result, our debt-fueled consumption created unsustainable asset bubbles.

This heavy reliance on credit-driven growth resulted in significant structural imbalances, notably the widening gap between household income and spending levels. By the end of 2008, American household debt sat at an astronomical 130% – that is, 30% more than average annual net household income – while the rates had plummeted from their level two decades prior, coinciding with the onset of the financial crisis.

Now central bankers face the monumental task of attempting to raise interest rates, even slightly, given that the debt-to-income ratio. Raise interest rates too much, and the entire economy risks tripping over its debt. People can no longer afford their repayments, leading to nationwide mass defaults, the collapse of the banking sector, and the demise of the ‘new economy.’

Yet, refraining from raising interest rates means forgoing an increase in the return on capital. Assets with low returns fail to inspire investment, in this case – investment into the United States. No investment, means no economic growth, therefore no job creation and less taxes. Tough gig.

This debt ratio unravelled to such an extent that many financial institutions could not meet their cash-flow requirements; they became illiquid. Actually, that’s putting it mildly, they became more than illiquid – they were insolvent and in desperate need of bailouts. The problem wasn’t that one big bank would fail but most big banks could fail at the same time.

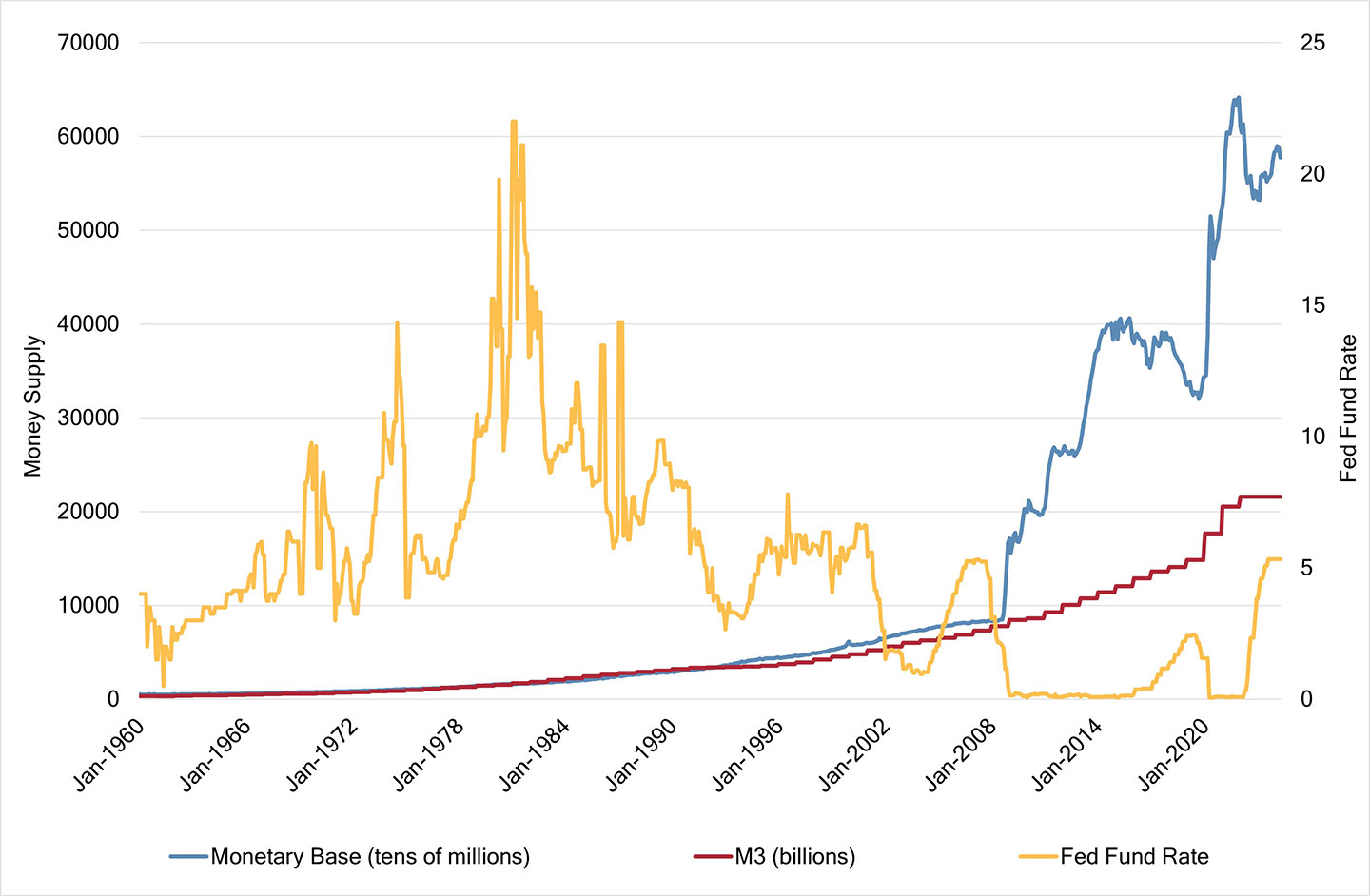

The Federal Reserve – aka ‘the Fed’ – was compelled to step in because their role is to act as the lender of last resort. On this occasion fiscal policy was no longer an option; and so monetary policy had to bear a greater burden than usual. (The Fed is the central banking system of the United States responsible for implementing monetary policy and maintaining financial system stability. Fiscal policyFiscal policy refers to the government’s use of taxation and spending to influence the economy. refers to the government’s use of taxation and spending to influence the economy. It involves adjusting tax rates and spending levels to regulate growth, employment, prices, and other macroeconomic factors. Monetary policyMonetary policy refers to the central bank’s control over interest rates and the volume and speed of the money that is circulating in the economy. refers to the central bank’s control over interest rates and the volume and speed of the money that is circulating in the economy.)

The fact that the US dollar is one of the leading reserve currencies – one that people put their faith in regardless of the immediate condition of the economy, because they believe the US will always recover and always pay back its debt – allowed America to be more experimental with its monetary policy. In this case, the ‘experiment’ was quantitative easing.

The Federal Reserve – aka ‘the Fed’ – was compelled to step in because their role is to act as the lender of last resort. On this occasion fiscal policy was no longer an option; and so monetary policy had to bear a greater burden than usual. (The Fed is the central banking system of the United States responsible for implementing monetary policy and maintaining financial system stability. Fiscal policy refers to the government’s use of taxation and spending to influence the economy. It involves adjusting tax rates and spending levels to regulate growth, employment, prices, and other macroeconomic factors. Monetary policy refers to the central bank’s control over interest rates and the volume and speed of the money that is circulating in the economy.)

Federal Reserve

The Fed is the central banking system of the United States responsible for implementing monetary policy and maintaining financial system stability. Fiscal policy refers to the government’s use of taxation and spending to influence the economy. It involves adjusting tax rates and spending levels to regulate growth, employment, prices, and other macroeconomic factors. Monetary policy refers to the central bank’s control over interest rates and the volume and speed of the money that is circulating in the economy.

The fact that the US dollar is one of the leading reserve currencies – one that people put their faith in regardless of the immediate condition of the economy, because they believe the US will always recover and always pay back its debt – allowed America to be more experimental with its monetary policy. In this case, the ‘experiment’ was quantitative easing.

The government ‘prints’ more currency and/or issues more bonds while slashing interest rates to basically zero, making the cost of money manically low – essentially free. The purpose of money printing is to make asset prices rise, while cheap credit further entices investors back into the market.

This shift was highly uncharacteristic for central bankers, who, prior to 2008, typically avoided encouraging inflation. When they transitioned from targeting inflation to using it as a tool, they went beyond merely providing liquidity. Instead, they started measuring their success by the levels of specific asset prices, such as the stock market and property values (for bankers higher equals better).

The Fed’s plan worked great if you only care about asset prices ‘right now’ and not how it might mess up the economy later. As more money circulated, demand for financial assets such as stocks and bonds surged, inflating their prices. However, investors grew bored of the unimaginative returns of these inflated “vanilla” assets. They wanted something more risqué.

So they turned their attention to derivative financial products, which offered larger gains… but greater risk. This fuelled a speculative frenzy, with investors trading derivatives (even derivatives of derivatives) built on top of the already inflated underlying asset prices. The increased leverage and complexity amplified risks in the financial system as a whole. (A derivative is a type of financial product that gets its value from another asset, like stocks or bonds. It’s basically a way to bet on the price movements of something else – like betting on whether the price of gold will go up or down without actually owning the gold itself. In other words, you’re not actually contributing anything tangible to society – you’re just betting on whether someone else wins or loses while they try and contribute something to society.)

You could say that the market now entirely relies on the ongoing assurance that the Fed and other central banks will always find a way to inject more cash into the economy to support asset prices at their unnaturally high levels.

Now that the Fed has emerged as a market maker rather than merely a lender of last resort, its importance cannot be overstated. Whatever actions or announcements the Fed makes has profound consequences for prices and markets.

To recap: since the 1980s, asset valuations have been artificially inflated, detached from their intrinsic worth or underlying economic fundamentals. Again, think housing prices. Despite this disconnect, banks continued to accept these overvalued assets as collateral. After all, why price things so depressingly low when there’s so much money to be made? This perpetuated a vicious cycle of debt-fuelled speculation and unsustainable growth.

The American banking crisis of March 2023 was a manifestation of this deep-rooted issue. To avoid a systemic collapse, the Fed intervened with the Bank Term Funding Program, providing ‘loans’ to distressed banks in need of liquidity. However, this program should be recognised for what it is: the greatest backdoor Wall Street bailout of all time.

None of this should have been particularly surprising, given that it was a textbook symptom of a diseased economy with outrageously inflated asset values coupled with a heavily indebted society.

The inevitability of the dollar system’s demise is grounded in a stark reality: the United States lacks the resources to sustain itself. Interest rates can’t go lower, yet they can’t increase either. Despite injecting cash into the economy, banks struggle to enhance their credit multiplier (i.e. make money from lending other peoples’ money to other people), as the effectiveness of credit is waning.

There’s an urgent need for genuine productivity growth in the real economy. Perhaps AI offers a solution, or it could be the next bubble waiting to pop, leaving only scattered droplets of progress.

This latest ‘second wind of growth’ could potentially last another six or seven years from its onset in the summer of 2021. Consequently, the next ‘Great’ Depression could hit by 2028, only exacerbated by a significant reduction in the global economy’s reliance on the US dollar.

A Shaky Alt-Alliance

While all of that is happening in the US, across that Atlantic a curious convergence has emerged between Russia, China, and Iran, not rooted in historical bonds, but rather in a shared response to Western sanctions and a mutual drive to counterbalance US influence.

In their view, it’s strange to hear the US advocate for ‘free markets’ as the best way to manage an economy, given that the US owes substantial debt to China, as well as many other nations. This debt has become so burdensome that America is willing to default through inflation; that is, by manipulating market prices via quantitative easing and requiring pension funds and similar institutions to increase their holdings of US sovereign debt, thereby bolstering demand for their own assets (at “gun point” or, at the very least, under government mandate). ‘Free market’ indeed.

This wouldn’t be the first time America has chosen such a strategy. Throughout history, the United States has resorted to inflation as a form of debt payment several times: from the American Revolution to the Civil War and Vietnam War – all effectively ‘paid’ through inflation. What’s that saying again? Fool me twice, shame on me?

This situation prompts several questions: Who exercises greater state control over the economy today, the US or China? Which economy exhibits more autarky (that is, economic self-sufficiency without relying on international trade)? Some argue that the US now engages in more state intervention than the countries it criticises.

This mistrust in American economic stewardship fuels the Eastern Bloc’s push to de-dollarise their economies. But unresolved issues, geopolitical ambitions, and diverging national interests could strain the alliance in the coming five to 10 years.

Russian Phoenix

Whether one supports Russia or not, from their point of view, NATO’s continuous eastward expansion is a blatant provocation. So their subsequent actions are coloured accordingly.

Amidst these escalating geopolitical tensions, European nations have distanced themselves from Russia, resulting in a sharp decline in Russian oil exports to Europe. In response, Russia swiftly redirected its focus to Asian markets, such as China and India, where their oil exports have more than doubled since 2022.

As one of the world’s largest oil and gas producers, Russia depends heavily on this sector, which contributes around 16% to its GDP, constitutes over 60% of exports, and provides a significant portion of government revenues. The one thing gnawing away at Russian government accountants would probably be the nation’s heavy reliance on oil exports. There has been, or perhaps now, was, a critical need for economic diversification and reduced dependence on dollar-denominated commodities.

While the sanctions imposed on Russia were intended to isolate and weaken the country, they have, much to the chagrin of the US, inadvertently compelled Russia to reduce its reliance on US products and services. Faced with these restrictions, Russia has been driven to develop substitutes through reverse-engineering for many once-monopolistic US products. If and when the US decides to re-enter the market (like Coca Cola is trying to do), they will suddenly have to compete with these new alternatives.

One of those exits was McDonald’s, now Vkusno I Tochka (Delicious, period), which raises the question of how The Economist plans to compare prices between different countries. The loss of the Big Mac secret sauce can be remedied with ‘Big Hit’ (the new Big Mac rebranded), but losing an economic indicator… now that’s just unconscionable. The last time the Big Mac index was calculated with Russia was in 2022, when a burger in New York cost more than three times as much as the same burger in Moscow.

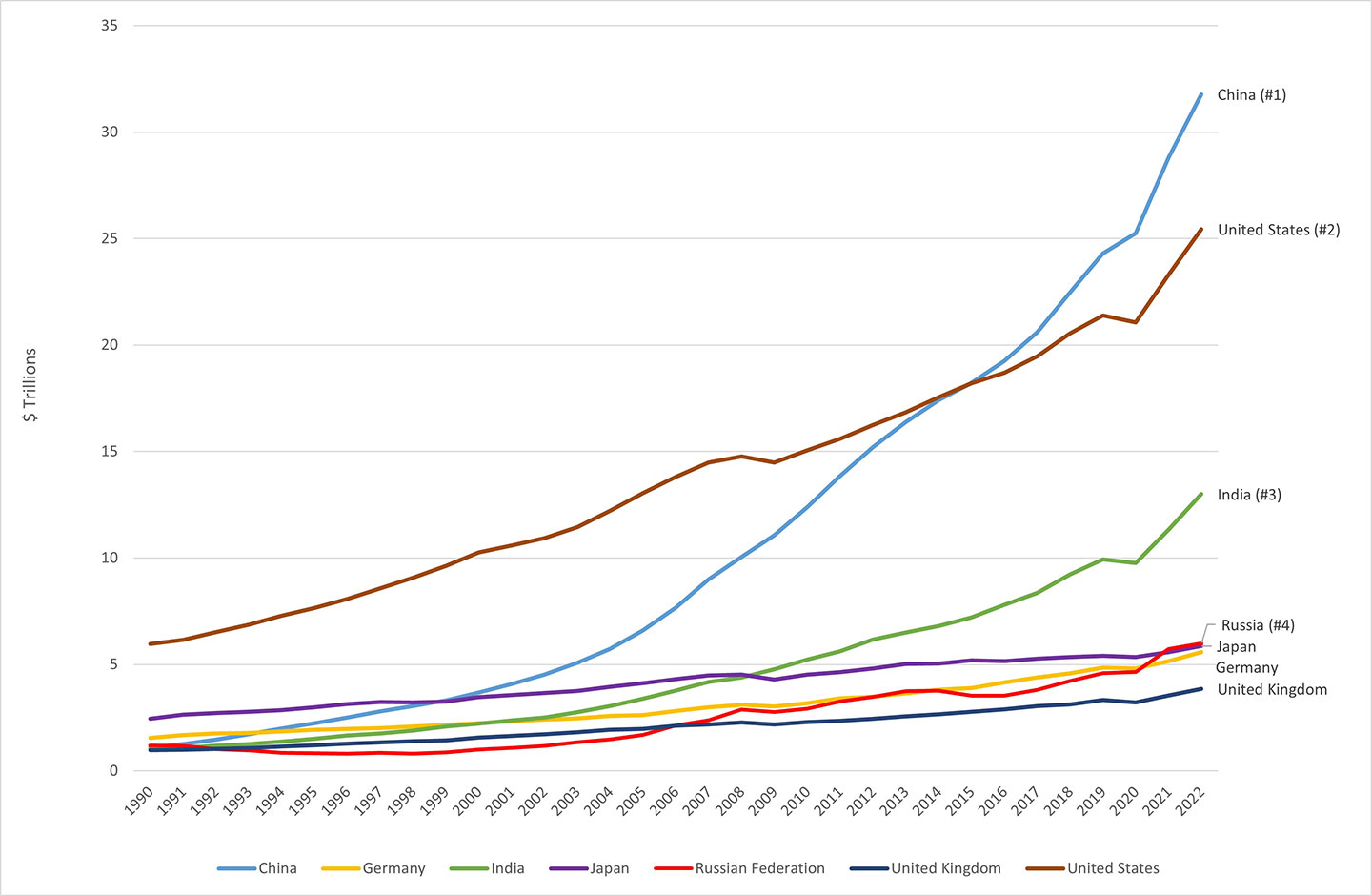

The World Bank has revised its Global Leading Economies data, improving Russia’s ranking. Now Russia is seen to have surpassed Japan in 2021 and has maintained the fourth position since then. Russian President Vladimir Putin had initially tasked his government with achieving economic growth exceeding the global average by 2025, so he’s ahead of schedule.

Before the conflict in Ukraine, Russia’s economy was lagging behind global growth rates, borderline stagnating. However, since 2022 the economy has experienced a boost, making it currently the fastest-growing major economy.

Never one to miss an opportunity, China, during this time, leveraged its economic ties with Russia to address its own challenges. It increased exports of higher-value goods such as cars and industrial equipment to Russia, basically using it as a testing ground. By 2023, Russia had become the top importer of Chinese cars, with purchases tripling compared to pre-sanction levels. So much so that Russian-Chinese bilateral trade turnover reached a record $240 billion by the end of 2023, marking a 26% increase from 2021.

The main weapon these countries have in their arsenal is their own currencies. Both Russia and China aim to ‘de-dollarize’ the global economy by increasing trade conducted in their currencies. This effort has resulted in ruble/yuan trade volume surpassing that of the US dollar. In June 2014, they signed the largest gas deal in history, agreeing to use only rubles and renminbi for gas payments. By the end of that year, the ruble’s share in Russia’s export payments exceeded 40%, surpassing their US dollar and euro trades.

Iran’s Going Dutch

Iran, much like Russia, depends heavily on oil exports, which constitute about 40% of total export earnings, of which over 80% exports to China. The country’s vulnerability to oil price fluctuations exacerbates economic challenges, a phenomenon often referred to as “Dutch Disease”. The only cure is for Iran to diversify its economy.

Unfortunately, efforts to establish new trading partnerships have encountered obstacles. While Iran has integrated into organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Eurasian Economic Union, its trade relations with Russia remain limited. Both nations primarily export oil and gas, making them competitors rather than natural allies; and when it comes down to it, Russia has a pricing advantage.

But don’t lose hope just yet! Iran has just opened up a new chapter with the Chabahar port deal recently finalised with India. This represents a significant economic opportunity for Iran, who can now start reducing their reliance on the US dollar in international trade. Hence the threat of sanctions they received from the US side. By establishing a direct trade route to Afghanistan and Central Asia, the port serves as a gateway for Iranian exports to access lucrative markets, bypassing traditional routes controlled by rivals or Western powers.

The Landbound Asian Dragon

Out of all the countries, it is actually China that would likely face the most significant challenges in the event of a potential collapse of the global dollar system. Such a collapse would deal a severe blow to China’s economy, given its extensive trade ties with the US, where imports exceeded $500 billion in 2023. But energy deals with Russia and Iran present crucial new avenues for China to diversify its trade relationships and lessen dependence on the US dollar.

Another thing for China to worry about: the only practical way China can bring raw materials into the country is on ships through the major shipping lanes that feed into its limited coastline. Some 90% of global commerce moves on ships, which happens to be one of China’s weak spots. It is dependent on shipping, since it lacks the infrastructure to lean on railways or airports, even though it fully intends to build some… eventually.

Air cargo and railways are expensive and logistically difficult. In the end, ships and shipping lanes are essential to China’s survival; but you look over your shoulder and there is the US Navy. Everywhere. Since the Second World War, the US Navy has maintained an ominous physical presence around China, from Guam to Pine Gap in Australia.

All of this to say that China feels geographically suffocated by the US’s death grip, and so acts accordingly. As China ascends as a global economic powerhouse, it actively promotes efforts to reduce reliance on the US dollar. In the past five years alone, the yuan’s presence in the global financial system has surged from negligible levels to nearly 3%, but still considerably behind the US dollar. Projections suggest that within the next decade, the yuan could secure a significant 5-10% market share, surpassing the yen and establishing itself as the leading Asian currency. Note that Japan is part of the Western bloc.

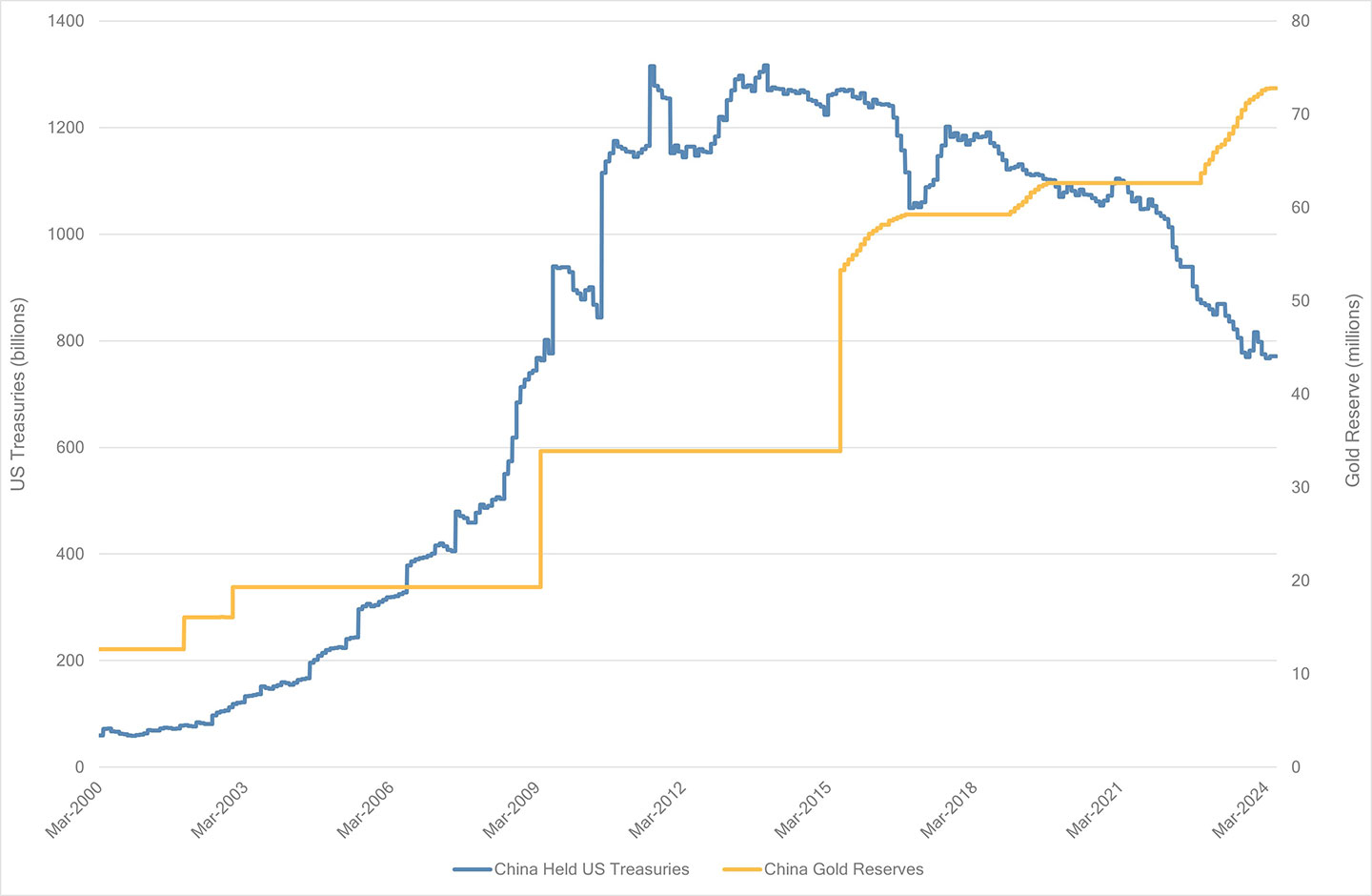

China’s shift away from holding US Treasury bonds, coupled with its rising gold purchases, underscores a strategic move to diversify its foreign exchange reserves and reduce reliance on the US dollar as the dominant global reserve currency. This strategy serves two key purposes: simple diversification and distancing from the West.

By offloading US Treasuries and accumulating gold, China aims to spread its investments across different asset types, thereby reducing any risks associated with overexposure to a single asset class. A simple case of not having all your eggs in one basket.

More importantly, this move is a direct response to escalating geopolitical and economic tensions with the West, especially after China observed how the United States treated Russia. By running this strategy, China hedges against potential US sanctions, asset freezes, or dollar devaluation. Concerns over the US’s mounting debt and persistent fiscal deficits also fan the flames.

Ultimately, this move signals China’s desire to diminish its dependence on the US dollar’s dominance in the global financial system.

Critical Decision

The US, which once commanded roughly 52% of the global economy in the aftermath of the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, now holds a significantly smaller share – around 30%, if we’re being optimistic.

Now they face a critical decision: whether to prioritise rescuing the real economy by relinquishing hegemony over the global dollar system, or to prioritise maintaining this system even if it comes at the expense of the real economy.

As the global financial system grapples with significant challenges, it becomes increasingly evident that a gradual transition towards a multipolar world is underway, rather than crowning a new economic hegemon.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.