In September 2021, New Matilda editor Chris Graham went from surfing almost every day to being air-lifted from a Queensland island, hospitalised almost a dozen times in 12 months, and bed-ridden for much of the rest of it. The trouble all started a couple of days after his second Covid-19 vaccination. In this special three-part feature, Chris explores ‘the good, the bad and the ugly’ of Australia’s response to the pandemic, and asks hard questions of himself and others about life, death and the morality of mass vaccination.

Thanks to a three decades long career as a journalist, my default demeanour is ‘bitter pessimist’. But courtesy of genetics and my upbringing, I’m also trapped in the body of a hopeless optimist. And that explains why it wasn’t until my Cardiologist was walking out of my hospital room that I realized what she’d just told me was actually very bad news.

“Would you like me to close the door?” she asked me gently.

“Sorry?”

“Would you like me to close the door?” she repeated.

“Oh, no, it’s fine thanks,” I replied breezily, and a little confused. Why would she offer to close my door, I thought to myself. It was open when she came in, and I’ve been here more than a week and it’s never been closed. And how good is it that I got my own room this time ‘round? Score!

A few minutes earlier, she’d tried to explain what was wrong with my heart. It’s all a bit of a blur in hindsight, but I’d written down ‘Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy’, which she encouraged me to read up on.

And again, ever the optimist, as she was explaining to me that there is no cure, and that in cases like mine, I might recover some heart function but it’s unlikely I’d ever get back to where I was, I zeroed in on the ‘unlikely’ part and thought to myself… ‘Yeah well, that’s what happens to other people. Not me. I’m 49. I’m fit. I’m strong. I surf most days of the week. I paddle out into the middle of the ocean and swim with whales and sharks for f*ck’s sake. And I don’t just do that on a normal, boring old surfboard. I tackle big swells on a Stand-Up Paddle Board. I am exceptional. I am invincible.’

Sporting delusions of grandeur aside, I was also spectacularly wrong. With the room to myself, I googled ‘Idiopathic Dilated Cardiomyopathy’. Turns out the ‘idiopathic’ part is just a fancy way of saying they don’t know the cause. I think I do, and so do some of the doctors and specialists I’ve seen since, but I’ll come back to that shortly. Because then, of course, I googled ‘Dilated Cardiomyopathy’ (DCM) and ‘life expectancy’… and it suddenly dawned on me why my cardiologist had offered to close the door on her way out.

What are the odds?

Twenty-five per cent of people with my condition die within the first year of their diagnosis. Half are gone within five years. That’s obviously shitty odds to begin with, but mine are made worse by the fact that in addition to DCM, I’ve also developed moderate heart failure, and I have electrical problems in three separate chambers of my heart. Or in the words of another of the multitude of doctors, nurses and cardiologists who’ve treated me over the past year, “Your heart is on fire.” If only I were a romantic and not a bitter pessimist/hopeless optimist….

To give you the briefest of explanations, DCM is a condition where the left ventricle of the heart stretches, weakening its ability to pump blood around your body. There’s no cure for DCM – it’s a life-long condition.

Heart failure is something else entirely. It’s more generic, more widespread, and basically concerned with how effective your heart is as a pump. That’s assessed in part by what’s known as your ‘ejection fraction’ – i.e. how much of the blood sitting in your heart at any given time is ejected every time your heart pumps. You might think that 100 per cent ejection fraction (EF) sounds like a good aspirational figure – I certainly did. But it’s not. A normal EF is anywhere between 55 per cent to 75 per cent. That is, half to three quarters of the blood sitting in your heart is pumped out every time it beats.

Heart failure is when that EF drops to 40 per cent or lower. In my case, I was first admitted to hospital in October 2021 at around 36 per cent. After a few months, I regressed further to 25 per cent. As for the electrical problems, let’s just say in my case ‘it’s complicated’. In addition to a few known arrhythmias, I have signs of ‘severe conduction disease’, which is just a fancy way of saying the wiring in my ticker was clearly done by an unlicensed sparky.

As for the practical effects of all of the above, when I first got into trouble, walking up a set of stairs could be a pretty epic undertaking. One afternoon when I was feeling better than usual, I decided to go for a beach walk. I made it a kilometre before realising I still had to somehow make it home. The return journey took an hour.

Some days I would wake feeling literally like death warmed up, which is pretty unsettling for someone used to bouncing out of bed. Standing at a sink washing dishes was also a huge challenge. I used to get out of doing them by claiming my ‘sensitive skin’ couldn’t handle the hot water. But in the early days of a dicky heart, I could only stand at the sink for a few minutes at most before my back started to give way, courtesy of a lack of blood supply to my muscles.

The best way I can describe DCM, with the greatest of respect, is that having it along with heart failure and a few arrhythmias is what I always imagined it would be like to get really, really old. Everything is a bit of a struggle, and long naps throughout the day are no longer just a luxury. They’re non-negotiable.

This article in The Conversation explains DCM reasonably well, plus it’s about musician George Michael of Wham! fame, who died from it. In any event, once the news from my cardiologist had sunk in, I did what any self-respecting investigative journalist would do… I joined multiple Facebook support groups. That was my first mistake.

As the name implies, support groups on Facebook aim to be ‘supportive’. But the problem with that is what ‘support’ looks like depends on your perspective, and from mine, I don’t like my news sugar-coated. I just want the facts, which is something Facebook’s not exactly known for. If I’m going to die, then just tell me I’m going to die, and I’ll deal with it as best I can. Don’t tell me ‘everything will be okay if you just stay positive’, because ‘positivity’ won’t help me up the stairs nor will it get the dishes washed. And it certainly won’t cause my heart to shrink back to its normal size, nor improve my ejection fraction. In particular, I like to avoid phrases like: ‘Don’t believe what you read on Google. I’ve lived with DCM for 20 years, and I’m doing fine!’

All of the support groups I joined were thick with that sentiment, which I can appreciate was intended to lift me, and others, up. But while it’s certainly true that there are many people who’ve lived many years with DCM, and managed their lives quite well, that’s actually how statistics work. If half the number of people with DCM die within the first five years – and they do – that means the other half live more than five years. The problem is, you don’t get to hear from the first half, or from the 25 per cent who died in the first year, because… well, let’s just say they’re not as active on social media as they used to be.

Joining those pages, for me at least, felt like an exercise in confirmation bias, but with a megaphone of denial in an echo chamber of toxic positivity. Which sounds a bit harsh on reflection, because from my experience, the people I met there were overwhelmingly nice folk, and they fundamentally meant well. But I also quickly formed the view that it just wasn’t the place for me.

As Henry David Thoreau once said, “Rather than love, than money, than fame, give me truth.” I like that sentiment, but it’s obviously also a bit over the top. You can have any combination of that three and truth without too much hassle. But then, old Henry was always a bit dramatic. Plus in my case, the truth, like my heart problems, is complicated.

Making waves

Speaking of drama, I promised earlier to explain how this all came about. Or at least how I think it may have come about, because as we sit today – a year and a few months in – the causes are either contested or unknown, depending on your perspective and in particular your qualifications.

What I do know almost to the minute is when everything started to go south for me. It was 7:35am on Sunday, September 12, 2021 near the appropriately named South Gorge, a spectacular spot in the far north eastern tip of Minjerribah (North Stradbroke Island), a semi-tropical paradise on the outskirts of Brisbane, Queensland.

Quite apart from Minjerribah’s role as a tourist mecca – on any given day you can see dolphins, turtles, manta rays, eagle rays, sharks, and Humpback Whales – South Gorge also happens to be home to my favourite surf break. That’s despite the fact that 18 months earlier I’d broken my ribs there in a big swell.

This particular Sunday morning, I didn’t really want to go out – it was overcast, and chilly. Stand Up Paddleboarding (SUPing) gives you a very good workout on the flat water of a lake, by smashing your core, arms and legs all at once. But riding a SUP in the surf is the same workout on steroids. Multiplied by 10. That said, I promised myself I would go out because I’d spent Saturday on the couch.

The day before (Friday), I’d had my second Covid-19 vaccine (Pfizer) in preparation for a trip south to Wilcannia, a remote Aboriginal community in the far west of NSW under siege from a Covid-19 outbreak, and official government neglect. But by Saturday the jab wasn’t agreeing with me – I was lethargic and just felt generally unwell, so I spent the day surfing the net, rather than the island.

By Sunday, I was feeling better, plus the swell had picked up, maybe two metres or so. While punching out through big waves on a SUP is never particularly appealing, surfing does happen to be an actual religion, and I consider that not going out on a Sunday without a very good excuse is blasphemous. So out I went.

As I paddled into the break zone, I could see a big set rolling in. I just managed to punch over the top of the first wave (surf SUPs are way too buoyant to duck dive under waves like you do on a normal surfboard) but I didn’t quite escape the suck of the breaking wave. I was pulled back ‘over the falls’, dumped heavily, then dragged backwards underwater for 46 metres. I know the precise distance because I was wearing a fitness watch, which records everything like time and average heart rate, even my exact route.

Needless to say, it was a wild ride, but one I’d enjoyed many, many times before. As the board was dragged along in the whitewash, I bounced along the bottom of the sea bed, like a human anchor on a boat. I acknowledge that sort of adventure is not necessarily for everyone, but personally, as a fairly solid bloke, I genuinely love it. Where else can you get rag-dolled around like a kid, without losing skin?

When I finally came up for air, I realized I’d lost a lot of ground, and figured I’d better move my arse, otherwise I’d get smashed by another set. I climbed back on the board, pointed myself out to sea, went to paddle and… nothing.

Literally nothing.

My breathing was laboured, but I’d just had a thorough dunking. But I also had zero energy, like my tank was completely empty. That’s despite the fact I’d entered the water only a minute or so earlier. Trying to paddle felt like I was moving in slow motion. It was the strangest feeling, and completely foreign to me.

Good luck, not good management saw me narrowly beat the next set and make it out the back of the waves, where I sat for the next 20 minutes, absolutely spent and unable to stand up. My legs were like jelly and I couldn’t seem to properly catch my breath. My watch records a heart rate for the next 20 minutes of 184 beats per minute. At 49 years of age, that’s uncomfortably high. And that was just the average. I drifted around behind the breakers like flotsam for another 40 minutes before belly-riding it back into shore and slinking back to my car. Defeated, I spent the remainder of the Sunday back on the couch.

Up until that point in mid-September, my watch records me surfing eight out of a possible 12 days. It also records me surfing 21 days in August. But after that morning, I surfed only once more during the month of September, and only a handful of times throughout the month of October.

Exercise just seemed harder than usual. I put the sudden drop in output down to an exhausting year. But what I didn’t realize was that I was developing all the signs of something far less innocent than simple lethargy. On October 18, my right leg became so swollen that I thought it was funny. So I took a photo and sent it to a close friend, laughing about how ridiculous it looked.

The reason why no alarm sounded is because my right leg was always a bit swollen – I trashed the central vein after an ice hockey accident in 2007 (I tore a hole in my stomach with my own stick, then developed a huge Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) in my leg, followed by two pulmonary embolisms plus a life sentence on blood thinners). I was also getting palpitations in my chest, but that was also ‘normal’ for me. Ironically, when I had the ice hockey accident, I was in the middle of going through the motions to determine whether or not I had some sort of heart arrhythmia. I had to wear a Holter monitor during a hockey game to see what my heart did – it got to 245 beats per minute, which is definitely not recommended. Unfortunately, before we solved the heart mystery, I had the ice hockey accident, and the heart investigations got put on the back burner. Then, over time, forgotten.

By mid-October, my stomach was also starting to bloat, and despite being relatively fit, I could lie down and ‘jiggle it’. I put that down to ‘excess fluid’ from not exercising as often as I should over the last few weeks.

The most bizarre symptom – which I didn’t even know was a symptom until a doctor asked me about it later in hospital – was that I had suddenly started adding more pillows when I slept. I noticed it at the time, in passing, but thought nothing of it. Four pillows seemed a bit silly, but I just figured I needed to sleep more upright as I got older.

What I didn’t know then, but obviously do now, is that these are all potential signs of heart failure.

Oblivious to it all, my final surf session at Minjerribah was a monster three-hour, 8.42 km paddle on October 30, 2021, which took me across the top of the island, through ‘Shark Alley’ (you can guess why the locals call it that) and down the right-hand side to Frenchman’s Beach, a notorious spot just north of South Gorge that’s great for surfing, but occasionally fatal to swimmers if you’re silly enough to ignore the warning signs.

The whole session was a struggle. I felt like my body was punishing me for the limited exercise I’d been doing and I resolved to try harder the next week. The following day I saw my GP about a skin cancer on my nose, but also explained that exercise felt a lot more challenging than it should, and that I was having more and more palpitations. She suggested I come straight in if I felt them, and they’d try and catch it on an ECG machine.

Two days later – five weeks after my second Pfizer shot – I was being airlifted from Minjerribah by an evac team from QGAir.

Down, Up And Away

Generally, it takes a bit over two hours to get from Minjerribah to the Princess Alexandra (PA) Hospital in Brisbane. There’s the 20-minute drive on the island itself – Minjerribah, the second largest sand island in the world behind K’gari (Fraser Island), is almost 40 kilometres long – then it’s 50 minutes across the bay on a car ferry, then another hour or so to the PA, depending on traffic.

By helicopter, it’s a 12-minute flight, plus you don’t have to look for parking at the end. Apart from the cost, the only downside I can see to commuting by helicopter every day is that it’s very, very noisy. Unless you’re hooked in to one of the headsets, you can’t hear anything beyond the roar of the rotors, and you certainly can’t communicate verbally with the people around you.

That explains why, shortly after we lifted off, the doctor leading the evac team leaned forward and showed me his phone. He’d typed, “Your numbers are good. You’re safe.” He’d added a smiley face at the end, which I thought was a pretty nice touch. Just prior, I’d watched my heart rate – which was visible on a monitor off to my side – jump from low 40s to more than 160 beats per minute, for no apparent reason. The look on my face, I’m assuming, suggested alarm, hence the doctor’s message.

Before we’d taken off, I’d asked him, “I’m a journalist, do you mind if I film this?”

“Sure, why not,” he smiled. Which is how I came to film my own evacuation on an otherwise uneventful Thursday afternoon from a sunny Queensland island. As stories go, this was going to be a cracker, I thought. I obviously had no idea how sick I really was, or how radically my life was about to change.

When we arrived at the PA, things unfolded precisely as you might imagine. When the chopper doors burst open, there was a huddle of serious looking people in masks ready to go about serious looking jobs. They worked quickly and precisely, with the sort of quiet efficiency that makes me question whether robots will ever truly be able to do what humans are capable of in a crisis.

I was rushed downstairs straight into the emergency department – no waiting, another perk of being brought in by chopper. My first and still one of my most vivid memories of the past year and a bit is of a group of nurses and doctors huddling around a screen monitoring my condition, and then occasionally turning to look at me with a mixture of curiosity and confusion.

Apparently, my heart rate was jumping all over the place, from very fast to very slow, and everything in between, along with jumping in and out of various rhythms. Things got so ridiculous that one of the nurses finally turned to me and, half-joking, asked, “You’re not controlling this are you?” I definitely wasn’t, although as I would realize over time, to some degree I actually could.

Very early in proceedings, one of my Cardiologists taught me a trick known as the ‘Valsalva manoeuvre’, which is designed to bring a racing heart rate back under control. While you’re lying in your hospital bed, the Valsalva involves ‘bearing down’ like you’re trying to poop while constipated. It’s not the most comfortable of procedures – physically, or emotionally, particularly in front of an audience – but in my case, it proved very effective.

When my heart rate would inexplicably jump to 160bpm or so – which would happen multiple times a day, for no apparent reason – alarms would go off and nurses and doctors would come running, ready to resuscitate me.

My airlift and maiden hospital visit was way back in October 2021, and since then, I’ve been re-admitted to hospital a further eight times, four of them in Brisbane, and four at the Prince of Wales Hospital (POWH) in Sydney. I’m proud to say that during all my stays, I performed the Valsalva to sell out crowds of doctors and nurses, and in particular students, and not once did I ‘lose control’ and ‘follow through’, which if you’ve ever had any experience with the move, you’ll know is an ever-present threat.

Then things got serious

Two of my most recent hospitalisations were not heart-related. In mid-October 2022, I visited my GP for what we both thought was a mild eye infection. Later that evening, I was in an ambulance on my way to POWH with excruciating pain radiating out from just below my chest. Turns out I was suffering an acute attack of pancreatitis, the cause of which remains a mystery to this day.

As luck would have it, the morning after my arrival my ‘eye infection’ had somehow managed to spread to my face and scalp… I spent the next two weeks in hospital with Shingles, followed by two more admissions, one of which included a suspicion of meningitis (or possibly encephalitis) courtesy of some pretty ‘out there’ hallucinations. Like the pancreatitis attack, the cause remains a mystery, although unlike the pancreatitis, I do have some fond memories of it. A lot of the hallucinations (which a close friend had the foresight to film) I have no memory of, whatsoever. But a particular set of them I do recall vividly… twice I was caught trying to sneak into rooms where Covid-19 patients were being isolated, because I was convinced friends of mine were in there waiting to stage a surprise ‘get well concert’ for me.

This is just a personal opinion, but if you were somehow given the choice between Dilated Cardiomyopathy – notwithstanding its potentially life-limiting nature – and Shingles, my very strong advice would be go for the heart condition.

More formally known as the Varicella Zoster Virus (VSV), Shingles is the adult version of Chickenpox, which, like most folk, I had as a kid. What I didn’t know then, but know all too painfully now, is that once you get over Chickenpox, the virus doesn’t die, it lies dormant somewhere in your nervous system, waiting for a chance to re-emerge in all its glory as a full-blown Shingles outbreak.

Where that occurs on your body depends on where the virus was hiding. The most common place is in a band around your waist, which makes lying down pretty challenging. But the virus can sit virtually anywhere there are nerves, and obviously, your body has nerves everywhere. Particularly in your head and face. That’s where my Chickenpox decided to hide out 40 or so years ago, and so that’s where my Shingles decided to break out a few months ago. That, and in my right eye.

Shingles is bad enough wherever you get it, but the term ‘miserable’ doesn’t even begin to describe what it’s like having it on your face and in your eye. It’s so shithouse that the only way I can think to describe it is ‘obscene’. As in, ‘I have suffered an obscenity’. Generally, I reserve those sorts of fighting words to describe, say, lunch with Alan Jones, or waking up drunk beside Tony Abbott or Eric Abetz and having no memory of what I did the night before. But Shingles of the face and eye has forced me to reconsider what an outrage really is. Although on reflection, the word ‘Demtel’ is another that fits, because when it comes to Shingles, wait, there’s more. So much more.

In about one in five cases, Shingles kicks the shit out of your nerves so thoroughly that you develop a condition known as Postherpetic Neuralgia (PHN), and that’s where the fun really begins. In my case, I had (or rather, I have… it’s still weaving its magic) Postherpetic Neuralgia of the Trigeminal Nerve. Translated, that simply means ‘After a Varicella Zoster Virus from the herpes family (postherpetic) you developed nerve pain (neuralgia) in your face and scalp and eye (Trigeminal nerve)’.

Its location and intensity is only a small part of the obscenity. What makes PHN so thoroughly awful is its longevity. It can last months after the Shingles rash has cleared, or even years. Or until the day you die, which in some cases you might consider a relief, particularly if it settles into your Trigeminal nerve.

And I mean that literally. A condition similar to mine (basically the same problem, but with a different cause), called ‘Trigeminal Neuralgia’ is known as the ‘Suicide Disease’. Widely regarded as the most painful condition known to humanity, the renowned Mt Sinai Hospital in New York describes it thus: “Unpredictable bouts of severe pain that makes everyday living unbearable. Every aspect of life becomes shrouded in currents of unrelenting shocks to the face, causing both physical and mental anguish”.

This is the part where my luck picks up a little: to this day, I haven’t fully recovered vision in my right eye, which drips like a tap all day, every day. And I’m on some pretty kick-arse nerve pain medications, which are doing God-only-knows-what to other parts of my body. But while I’m a long way from being pain free – at completely random times of the day it can feel like my face is being electrocuted – I can still function. It just means that occasionally I pull a face that makes it look like my finger is stuck in a power socket.

Surprisingly, that still makes me one of the ‘lucky ones’, or maybe one of the ‘lucky unlucky ones’, because a lot of people in my situation aren’t faring nearly so well. Mind you, they probably don’t also have heart problems to deal with, but in my experience, cardiac issues exhaust you, and occasionally make you feel like death warmed up, but it’s not painful. For the first full year of my heart condition, I was very aware of, and grateful for, that fact. Shingles and PHN radically changed all that, and so I found myself once again circling the Facebook support groups.

For me at least, I found contemplating my mortality – as I was forced to do in the early stages of my heart failure – something best done alone. Well, more or less alone: I had a psychologist (Lena), who was a huge help, and a close friend who was even more so. I guess I mean that the input of complete strangers, regardless of whether or not we had something terrible in common, wasn’t that helpful for me. But as Shingles and PHN forced me to discover, the questions you ask yourself about your mortality are quite different when you’re in constant pain.

Suffice to say, I’m a member of several Facebook PHN groups, and I’ve found connecting with people who know what it feels like to have your eyeball scooped out with a hot spoon (metaphorically speaking) comforting. Or maybe, to quote English naturalist and botanist John Ray, a man far less prone to hyperbole than Thoreau, “Misery loves company”.

And a note to readers: The Australian Government funds a Shingles vaccine (free in many cases) which is very effective. From someone potentially with good reason to be a little ‘vaccine shy’, if I could turn back time I’d take the shot in a heartbeat. Pun intended.

The good

The elephant in my room, obviously, is whether or not the Pfizer vaccine played a part in my heart issues, and even some of the extra silliness that followed. The truth is, I don’t know. Some doctors believe it did. Some believe it didn’t, and some are still having a bet each way. In all likelihood, that will probably be how it remains – the great mystery of my life.

My personal view is that the vaccine probably did play a part, because the timing of when everything started to go wrong for me – two days after my second Pfizer shot – is just too hard to ignore. But if I had to bet my life on it (irony intended), there’s a few issues that might have me hedging my bets too.

Firstly, I’m an ex-smoker, which increases my risk of cardiac events. Secondly, I have a significant family history of cardiac events at early ages. And finally, as mentioned above, I have a history of Supraventricular Tachycardia (SVTs), which means occasional rapid heartbeats. That’s not a death sentence by any means – lots of people have all sorts of heart murmurs, flutters and palpitations including SVTs without keeling over – but as I mentioned earlier, when your heart rate during exercise gets to 245bpm and you don’t even notice it, it suggests something else might be going on.

So I don’t know if the vaccine is responsible for my heart problems. In the words of one of my GPs, “… it might have been enough to tip you over the edge”. But there are other factors beyond my genetics which also have to be considered.

All vaccines cause some injury to some people. That’s a fact of life, and a reality of living in a responsible society. We mass vaccinate populations for the greater good, understanding that while a small number of people will suffer, the majority will flourish. Our diversity is actually one of the reasons humans are so prolific and successful as a species – it ensures that when something nasty like a virus comes along, it might get some of us, it might even get a lot of us, but (so far at least) it won’t get all of us.

It’s also simple math that if you’re forced to vaccinate a large population over a short period of time, then you’re going to have a larger number of injuries over a shorter period of time, injuries that in another context – for example, one outside a pandemic – would be spread over a much longer period, and would go unnoticed by media and the general public. It’s a bit like that old trope of buying a new purple car. Now, suddenly, you’re noticing purple cars everywhere. The purple cars were always there, it’s just now they’re on your radar. Or in the context of Covid-19 vaccines, almost everybody in the country bought a purple car all at the same time, so you literally are seeing them everywhere.

The equivalent of that trope in the news at the moment seems to be otherwise healthy athletes collapsing, mid-game. It’s been jumped on by some as proof that the vaccines – in particular the mRNA vaccines (Pfizer and Moderna) – are killing people. The most recent example was early January in the United States, when National Football League player Damar Hamlin, aged 24, suffered a sudden cardiac arrest during a game.

The fact is, athletes collapse on the field all the time, and always have. And they do it in numbers that might surprise you, but because they’re not in the shadow of a mass vaccination event, it doesn’t make the news.

A US study published in July 2020 – so before vaccinations for Covid-19 were a ‘thing’ – set out to determine the cause of “sudden cardiac arrest and death (SCA/D)” in competitive athletes. It looked at 179 cases of SCA/D over a two-year period, in ages ranging from 11 to 29; 105 of them died, while 74 survived. The study concluded: “The [cause]of SCA/D in competitive athletes involves a wide range of clinical disorders. More robust reporting mechanisms, standardized autopsy protocols, and accurate… data are needed to better inform prevention strategies.” In other words, they don’t really know what caused the injuries and death, beyond “a wide range” of issues.

An even broader study published in November 2021, looked at 331 cases of confirmed SCA/D (158 survivors; 173 fatalities) over a period of four years (July 2014 to June 2018). That equates to one incident every four to five days. There’s no evidence yet of an increase in ‘athlete deaths’, but you can almost guarantee that if it happens, it will be discovered – there’s simply too many eyes watching now for any other outcome.

Of course, it’s not just athletes who keel over. One of the best ways to find out if and when people are dying is to rely on ‘excess mortality’. It’s basically the number of people who died in a community, set against the number of people who were expected to die. If you have an excess of deaths, then you have excess mortality, not to mention some serious questions to answer.

The reason why it’s so useful in the case of the pandemic is that it accounts not only for Covid-19 deaths, but also deaths among people who, say, delayed getting medical attention during the lockdown, or other deaths related to the pandemic such as suicides caused by social isolation.

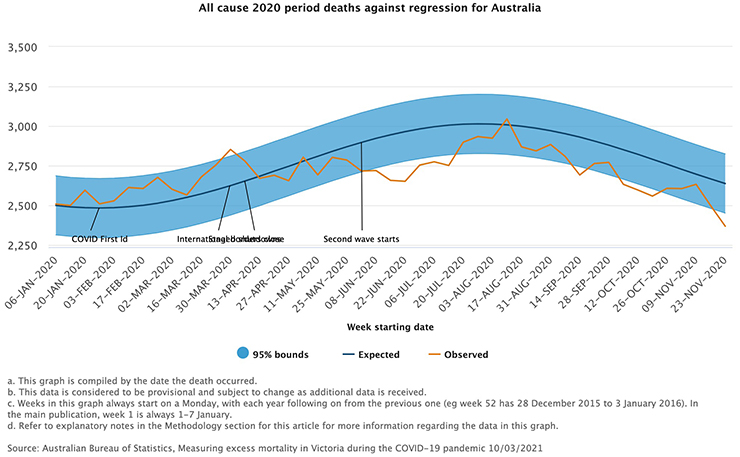

During the first year of the pandemic, the excess mortality rate was actually down in Australia thanks to the lockdowns, which kept people off roads and prevented the seasonal flu from spreading among the population. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS): “Over the period from January to November 2020, Australia recorded lower than expected mortality (see graph below) with decreases in the winter months being statistically significant. Lower than expected numbers of deaths were particularly notable for respiratory diseases including pneumonia. This is in contrast to many other countries where excess deaths have been recorded during the pandemic.”

However, in the latter stages of the pandemic, excess mortality rates have risen, and quite significantly (an additional 15,400 deaths in the first eight months of 2022). According to the ABS, excess mortality sits at 16 per cent. The ABS has a good article on Australia’s excess mortality in 2022 here, but long story short, the Actuaries Institute (which also keeps numbers on excess mortality, and estimates the rise at 12 per cent) puts it down to Covid-19, not the vaccines created to fight it.

Some more good

There’s obviously no doubt that the vaccines used in Australia have caused injury. How many and how serious will be like trying to unscramble an egg – we’ll almost certainly never know the full extent. But what we do know for certain is that the vaccines have also saved a lot of lives. That’s a statistical fact. This feature was never intended to be a ‘war and peace’ on the pandemic, or Australia’s response to it. It was only really supposed to explain to readers what had happened to me, and where I’d been for the past year and a bit. But the more I researched and the more I read, the more I came to understand how different groups – some pro-vaccine, some anti – distorted facts to make their case. Sometimes it was deliberate, sometimes it was just born of ignorance.

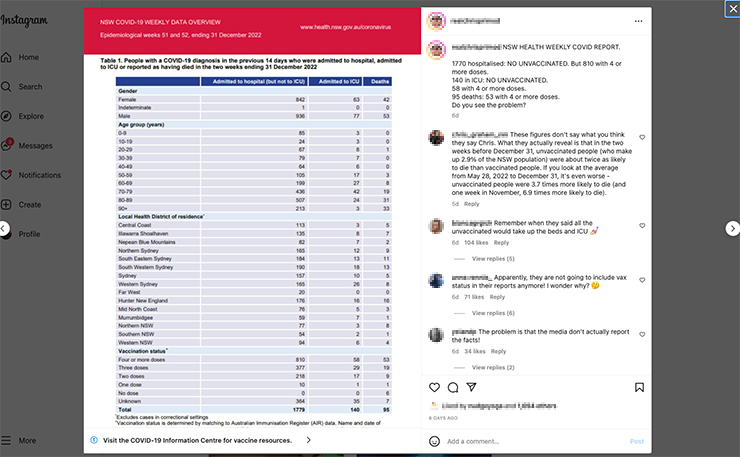

One of the more egregious was a recent post from an Instagram ‘influencer’ adamant that vaccinated people were dying in much greater numbers than unvaccinated people. As proof, he posted a screen shot of data from the NSW government which covered the last fortnight of 2022 (December 14 to 31), showing 95 deaths. Just six of those deaths were among unvaccinated people. This was proof, he argued, that it was the vaccinated, not the unvaccinated, who were dying. The truth is something else altogether.

Vaccinated people in NSW are dying in greater numbers, which is exactly what we would expect to see. That’s because there’s a hell of a lot more of them. In NSW, 97.1 per cent of the population is vaccinated, which means just 2.9 per cent are unvaccinated. So, if unvaccinated people died at the same rate as vaccinated people, then they should make up just 2.9 per cent of deaths (or less, because as some claimed, unvaccinated people were actually less likely to die). In the numbers posted by the influencer, unvaccinated people made up 6.3 per cent of deaths… almost double the rate at which they should be dying. But if you expand the calculations out six months or so (as I did in the graph below, from May to December last year), on average unvaccinated people died at a rate almost four times greater than vaccinated people.

The bottom line represents the numbers of unvaccinated people in NSW who should have died, while the top line represents the actual number of deaths. The difference is obviously pretty stark, and the data shows clearly that unvaccinated people got sicker, and died at greater rates. That’s consistent with the experience internationally, and the scary part is it could have been a whole lot worse.

When Australia first started locking down in March 2020, we were still dealing with the original strain of Covid-19, which was far more deadly than the variants dominating today. After Victoria locked down for its first major wave in June 2020, the Case Fatality Rate (CFR) – that is, the percentage of people who caught Covid-19 and then died – by the end of the crisis was a staggering 4.3 per cent.

To give you some context of just how bad that number is, and how many people in Australia could have died had we not locked down, if our national CFR matched Victoria’s from the start of the pandemic until today, the number of dead would be in the hundreds of thousands.

As it stands, our Covid-19 death toll recently passed 17,000. If you compare that to three years of influenza (2017 to 2019), where 2,231 people died, Covid-19’s death toll is almost eight times greater, and that’s with a mass vaccination campaign and some of the most restrictive lockdowns in the world.

One of the questions people are still asking is whether or not those lockdowns were worth it. Well that depends on your value system, but from my perspective, I reckon saving a few hundred thousand lives – in particular elderly and vulnerable Australians – is a pretty good outcome. And how that came about is something for which I think all governments in Australia can take significant pride.

From the start of the pandemic to November 6, 2021 Australia recorded 178,946 Covid-19 cases, which ranked us 99th out of 219 countries. But our rate of infection - the number of cases set against our population of 26 million people – ranked us 161st, which is even more extraordinary. Other comparable performances at the time (by developed nations with reliable health data) were New Zealand, Taiwan and Singapore.

Fast forward a year later to November 6, 2022, which was almost 12 months after most Australian governments eased lockdown restrictions and, in the words of their critics ‘let the virus rip’, and Australia had 10,418,986 cases, and was ranked 14th overall in total cases. That is by any measure a staggering increase. But the statistic that ultimately matters – the number of deaths – shows undeniably that the Australian response to Covid-19 was amongst the best on earth.

Our ‘deaths per million population’ rate was one of the lowest on earth, and what’s most notable about that is that the virus has already spread widely throughout Australia. Some other nations with lower death rates, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, are yet to see mass infections, which means we don't yet know what the real death rate will be until the virus spreads more widely among their citizens.

Australia's success was undeniably the result of lockdowns, followed by widespread vaccination programs. So as a nation, we dodged a very big bullet. But at what cost? After all, nations are made up of people, and if a lot of those people didn't fare so well, then how big a price did we really pay? And what do we owe those who were harmed so the rest of us could get out of lockdown, and start rebuilding our economy?

The fact is, many more Australians were injured by Covid-19 vaccines than you probably realize, and the data the Commonwealth keeps on vaccine injury makes that abundantly clear. The problem is, that data isn't really worth the paper it's written on, but even then, the 'official' injury toll appears to be the literal tip of a pretty big iceberg.

* Part 2 of this special feature should have been published in January this year. However, the author ended up back in hospital for an extended period. Part 2 will now be published on New Matilda on Thursday, August 10, 2023.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.