SPECIAL INVESTIGATION: Data from Australia’s criminal justice system shows clearly that we’re failing to rehabilitate children, while making them more likely to reoffend. And yet kids as young as 10 are still being charged with criminal offences. Warwick Jones investigates.

A 10-year-old Aboriginal girl wearing pigtails and a school uniform walks into the Geelong Children’s Court, dwarfed beside two welfare workers. It’s late autumn, 2015. The girl’s been taken out of her grade four class to come before the court charged with stealing a phone.

She’d been removed from her family home and placed into state care. On the day of the alleged offence she was found in a neighbour’s car trying to call her mum.

The girl’s lawyer, Mr Ali Besiroglu, is at the time a senior solicitor at the Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service. He’s also a father to three kids not much younger than his client.

Besiroglu pleads with the police prosecutor to withdraw the case, but he refuses. So while they’re waiting for the magistrate, Besiroglu walks his client over to the prosecutor’s table and introduces him to the young girl he has up until this point only read about.

“This man is the prosecutor,” Besiroglu tells her. “He’ll be talking to the magistrate. The magistrate will sit up there,” Besiroglu points to the bench, “he’ll decide what happens here today. We’ll sit over there, and I’ll be telling the magistrate your side of the story.”

The prosecutor is polite to the girl. But he is angry at Besiroglu. “Why’d you have to pull that stunt?” he asks once the girl left. But it’s not a trick. The decision to prosecute a 10-year-old child shouldn’t be easy.

“Her case clearly highlighted to me that there needs to be reform,” Besiroglu said. “She was so small, she was scared, she was confused, and it was clear to me that whatever conduct she had engaged in, it wasn’t criminal.”

And Besiroglu is far from alone. In courthouses and legal chambers around the country the conversations are the same. Young children should not be in the criminal justice system.

Get ’em while they’re young

IN VICTORIA, the law allows for children as young as 10 to be charged with a crime, brought before the court, and locked up. The age a child can be held criminally responsible in every Australian state and territory is 10 — one of the lowest in the Western world and in breach of international human rights law.

In May, Victoria’s Youth Justice Minister, Ben Carroll, released a strategic plan outlining the state government’s 10-year vision for the youth justice system. The plan aims to reduce the number of young people in the system and improve community safety.

But the 53-page document makes no commitment to raise the age of criminal responsibility, instead abdicating the decision to the Council of Attorneys-General who are currently reviewing the age.

Yet there is a unified voice amongst experts calling for the government to raise the age of criminal responsibility. Smart Justice for Young People — which represents more than 40 legal, social, and health organisations in Victoria — is calling for the age to be raised to at least 14. As are academics, child’s rights groups, and Children’s Commissioners around the country.

Today, kids under 14 who are brought before the courts are presumed to be ‘doli incapax‘ — that is, they don’t have the capacity to commit crime because they lack a guilty mind. It’s up to the prosecution to prove that the child knew that what they were doing was seriously wrong.

“Any person would have known just by looking at this child that she was incapax,” Besiroglu told me. “But we had to go through this system just to have the case withdrawn.”

And the system isn’t cheap. In 2018-19 the Victorian youth justice system cost taxpayers over $250 million, including legal aid. Most of that was spent on locking kids up, which costs more than half a million dollars per child, per year, about five times their adult counterparts.

It took five months, four days off school, three trips to the courthouse, and a long drive to Melbourne before the Aboriginal girl’s ordeal was over. And it would have been much more had Besiroglu not gotten her a doli incapax report from the court psychologist.

“I’d be doing my client a disservice if I said, ‘Well, the police bear the onus to prove she has capacity,’” Besiroglu said. “Because I’d have to bring her back to court for a mention, for a further mention, for a contest mention, and then for a contested hearing, just to question them on this issue of capacity.”

Yet, some prosecutors are reluctant to withdraw charges unless there’s expert evidence to suggest the child does not have a capacity, essentially flipping doli incapax on its head.

“It’s not an uncommon story that a lawyer is tasked with having to represent a 10-year-old child,” Besiroglu said. “There’d be thousands of stories out there where the lawyer’s gotten a doli incapax report and the child’s walked.”

More harm than good

BUT it’s not as simple as ‘no harm, no foul’. There’s overwhelming evidence that the criminal justice system not only fails to rehabilitate children, but actually does them harm. And yet every year, Victoria Police charge thousands of children with criminal offences.

And many of them don’t walk. On an average night in 2018 there were nearly 1,000 kids behind bars across Australia. Most were on remand awaiting trial or sentencing, and most were Indigenous.

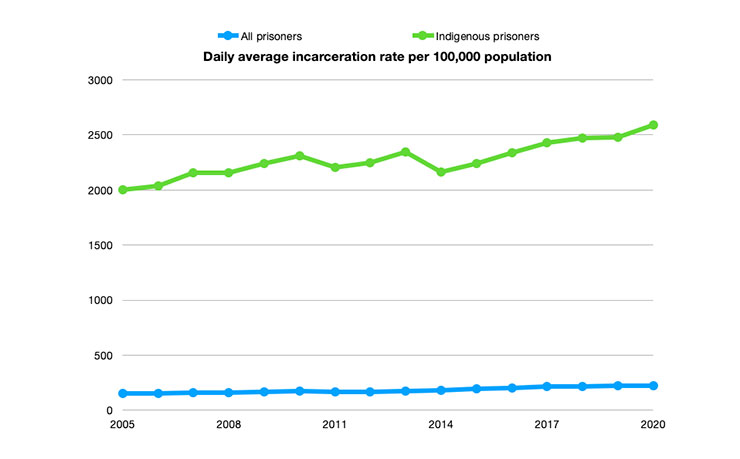

In fact, Indigenous Australians are the most incarcerated people on the planet. More than one in 40 Indigenous Australians are in prison, compared to just one in 450 Australians. Nearly one in 20 Indigenous men are in prison. And that number is only climbing.

The gap is even worse for children. An Aboriginal child is 14 times more likely to be incarcerated in Victoria than their non-Indigenous peers — 26 times nationally.

It gets worse. Last year, over two thirds of kids under 14 who were behind bars in Australia were Indigenous, and 80 per cent of 10-year-olds behind bars were Indigenous, making Besiroglu’s client closer to 100 times more likely to be imprisoned than an average 10-year-old.

And it isn’t because Aboriginal kids commit more crimes. She was more likely to be over-policed, more likely to be charged instead of cautioned, more likely to be charged on her first offence, more likely to be remanded than granted bail, more likely to be arrested, and less likely to be diverted for the same offence as her non-Aboriginal peers.

Brought home from half a world away

CIVIL unrest in the US following the death of George Floyd at the hands of police in May has brought national attention to the 432 Indigenous Australians who died in police custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into that very issue.

Few of the recommendations from that Royal Commission have been fully implemented, including many to do with youth justice. Were there to be another Royal Commission today, raising the age would undoubtedly be a recommendation.

Professor of Criminology at the University of Technology Sydney, Dr Chris Cunneen, co-wrote a book back in 1995 arguing that 10 is too young to criminalise children.

“The younger the child is when they come in contact with the youth justice system the more likely they are to stay within the system,” Cunneen said.

A child’s brain is still developing well into their late teens and early 20s. This means young kids lack the hardware required to properly link behaviour with consequences, significantly diminishing their executive functions.

But most of the kids who come before the courts have even less capacity than an average child. Most come from disadvantaged communities and families dealing with poverty, mental illness, and addiction. Most have some combination of mental, cognitive, or hearing impairment. Most are disengaged with school and have fallen in with the wrong crowd. And most are in state care and have been victims of violence and abuse.

Numerous studies have found as many as three quarters of kids in the criminal justice system have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder, including depression, psychosis, PTSD, and autism. And many struggle with substance misuse and addiction as a result of past trauma.

All of these factors greatly increase a child’s risk of offending by crippling their already undeveloped ability to control impulses, make decisions, and regulate emotions.

“If a child is engaging in problem behaviours, that should be a red flag that there’s something wrong in that kid’s life,” Cunneen said. “We don’t need the criminal justice system to tell us that.”

On top of failing to address the underlying cause of a child’s behaviours, the criminal justice system is also likely to do them serious and irreparable damage.

“We’ve interviewed youth workers, detention centre managers, magistrates, solicitors,” Cunneen said, “and I’ve never spoken to anyone in the area who thinks bringing a 10-year-old kid into the justice system is a good thing.”

The little girl charged with stealing a phone didn’t have the maturity or moral capacity to tell the difference between naughty behaviour and criminal conduct. So, trying to hammer it home that what she did was criminal is sure to go over her head, while reinforcing the behaviour and permanently labelling her as a delinquent.

By continuously telling her she’s a criminal, you’re likely to convince her that it’s true and entrench in her criminal conduct, commonly referred to as labelling theory. And a child who offended due to life circumstances beyond their control is particularly susceptible.

“Also, once you’ve been through court once or twice it becomes somewhat less of a scary place,” Cunneen said. “You normalise going before the courts and into custody.”

But prison should not be normal for any child. Kids in juvenile detention are taken out of school and away from their family, friends, and communities, and routinely strip-searched and placed into solitary confinement.

Locking kids up during such an important life stage can severely affect their development and greatly increase their risk of depression, suicide, and self-harm.

Youth detention centres in Victoria have been plagued with safety issues, rioting, and assaults. At the start of June, the High Court ruled the use of teargas against children at the Don Dale Youth Detention Centre in the Northern Territory unlawful after a Royal Commission found kids at that facility had been subjected to “regular, repeated and distressing mistreatment”.

Yet despite these ruthless conditions, juvenile prisons are not an effective deterrent. Cunneen told me children instead become institutionalised, make friends with other kids in institutions, and it becomes a “revolving door of kids going in and out of the justice system”.

Cops and shock-jocks

SO WHY, given this overwhelming evidence and consensus amongst experts, is the age of criminal responsibility in Victoria so low?

According to the lawyers, academics, and advocacy groups, Victoria Police and the police union are the loudest opponents of raising the age.

“They’d prefer to be able to deal with people the way they want to,” Cunneen said, “and raising the age places a restriction on what they can do. The police are the only players within the justice system that don’t support raising the age.”

There’s also a public interest in coming down hard on youth offenders, driven by certain parts of the media and stemming from a lack of understanding about the evidence or alternatives.

Some commentators have argued that raising the age would let kids get away with murder. But kids very rarely commit serious offences — most are charged with theft, public order, or drug offences. And Cunneen and others have suggested retaining doli incapax for kids under 14 charged with very serious crimes.

“Governments don’t want to raise the age because they don’t want to appear soft on crime,” Cunneen said. “It’s political. It’s not based on evidence, that’s for sure.”

Acting Legal Director of the Human Rights Law Centre, Ms Shahleena Musk, an Aboriginal woman from Darwin, is disappointed in the government’s youth justice strategic plan.

“The Victorian government has said that they want to be a leader when it comes to youth justice in Australia,” Musk said. “But their failure to commit to raising the age of criminal responsibility demonstrates that they aren’t so committed.”

The plan has some positives, Musk said, including early intervention, diversion, and restorative justice. But until legislators prevent police from charging young kids and change laws that unfairly affect the disadvantaged, Victoria will not be a “progressive or human rights compliant jurisdiction”.

And it isn’t like the Victorian government hasn’t had the opportunity to hear from experts and learn from their mistakes. There have been multiple inquiries, including a 2017 review of Victoria’s youth justice system that first recommended the government draw up its 10-year plan.

All of them recommended governments raise the age of criminal responsibility.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

“The criminal justice system is still a system that punishes and controls, and is designed to break people down,” Musk said. “It very much criminalises disadvantage, it criminalises vulnerability, and it criminalises trauma. And we’ve only made minor adjustments for children.”

But the supports and safeguards we afford kids in the justice system do little to protect them from the system. An Australian National University study released in June found three quarters of Australians have an unconscious bias against Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander people. And there’s no reason to believe police, prosecutors, or magistrates are immune.

The ANU study confirms decades of research and data suggesting Indigenous Australians receive unfair treatment before the law due to the prejudice of individuals within the justice system, unconscious or otherwise.

What’s more, relying on the discretion of those individuals exposes the system to other biases as well. They may throw the book at a kid simply because the child looks older than they are, comes from a rough neighbourhood, or because they think it’s the best course of action.

Musk worked as a public prosecutor in Western Australia in 2006. She said she had to self-educate about the best way to help the kids she was prosecuting.

“I didn’t know about child and adolescent development, I didn’t know about the impact of trauma,” Musk said, “and I thought ‘this kid’s had 10 chances, how many chances do you need?’”

Educating prosecutors and the police, who act as the “gatekeepers of the criminal justice system”, is an essential part of reform, according to Musk.

“There needs to be leadership within the institutions themselves,” Musk said. “Each agent of the justice system has to see for themselves that punitive measures don’t work.”

But the law itself has to change too, so that the solutions available to those agents are based on evidence and child rights.

Laws that criminalise health issues, like drug addiction, and laws that impose bail conditions outside of a child’s control, must go, Musk said. But most importantly, we must raise the age of criminal responsibility.

Without the option to arrest, charge, or imprison kids, we will be forced to look for alternatives that actually address the underlying causes of problem behaviours and provide support to the child and their family, just as we do now for kids under 10.

Ben Carroll, the Minister for Youth Justice did not respond to requests for an interview.

Victoria Police declined an interview.

Ali Besiroglu now works as a solicitor at Robinson Gill bringing civil action on behalf of victims of police brutality and the families of those who’ve died in police custody. You can read the post on his LinkedIn account which sparked this investigation here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.