With the new university semester about to start, Dr Nick Riemer asks what it means to devote years to higher education when the planet is literally burning.

In a few days, amid the most serious environmental crisis since European invasion, students in Australia will begin the new university year.

Only a small number of them will have been evacuated from holiday beaches during the worst of the summer bushfire inferno; even fewer will have lost homes or family members.

Everyone, however, will at least have seen the pictures, and many will have experienced for themselves the signs of an ecosystem pushed to breaking-point: blackened rainforests and incinerated wildlife, choked air, orange skies, the devastation of favourite places, the super-charged heat-waves.

On some undergraduates, it’s safe to assume, a frightening realisation will have dawned: what once was just the weather, the incidental backdrop to daily life, has now become an angry, unpredictable foe.

Enough students will also have registered the paralysis of the political class. Students have been at the forefront of the revitalized environmental activism that swept over the world from March last year with the first of the global climate strikes.

Young people are the most convinced of the urgency of zero-carbon economies, so politicians’ criminal delinquency on the issue, and the reactionary diversions they stage will not have gone unnoticed. This is, after all, a nation where our government honours a pedophile-apologist, while our opposition calls for patriotism pledges to be re-introduced to schools.

To many university teachers and students, this poses, in sharper terms than usual, the question of whether the studies they will soon be resuming have anything to contribute to social progress and, if so, what.

What kinds of higher education does society need in the interests of an emancipated, sustainable world, one constructed on different bases than domination and environmental destruction?

Soft critique

The colleagues and students I know all seem to agree about the dangers of global heating and the need for action. Many of us went on strike to march for the climate last year.

Humanities staff from @Sydney_Uni for real action on climate #Strike4Climate #schoolstrike4climate pic.twitter.com/bWwzoRKxk1

— Nick Riemer (@NickRiemer1) March 15, 2019

But as integral parts of modern economy and society, the universities we work in are part of the system leading us into environmental collapse.

Higher education supports the carbon-polluting activity that contributes directly to climate breakdown. It generates the different kinds of knowledge needed to secure economic growth and trains a workforce to apply them.

In the humanities and social sciences, it prepares the workers who manage and reproduce the institutions that sustain the economic system, fostering both ideological support of existing social power and just the right amount of soft critique of it.

Traditionally the privilege of a narrow elite, universities have never been meant to graduate revolutionaries. For decades, however, higher education has been the norm for more and more people. But this massification of tertiary-level study didn’t fully prise universities out of their traditional socket deep in the ruling classes.

Instead, in many countries, the liberal arts –non-vocational humanities subjects like philosophy, literature or history, central components of the traditional idea of the university – remain the province of students from higher socio-economic backgrounds.

More generally, the growth of university education accompanied the decline of the powerful working-class organisations – unions, and associated socialist and social-democratic parties – that were not only the motive forces of democratic politics in much of the West, but also, often, essential vectors of mass popular education.

Universities do not systematically or seriously challenge the system that is killing the planet. By acquiescing to the premises of the existing socio-economic order, higher education helps justify a world based on environmental destruction, ruthless competition, and limitless accumulation.

The humanities are often reservoirs of progressive alternatives. But they also play a subtle role in supporting the status quo, providing the ‘consolations of philosophy’ for an alienated existence in which people are treated as objects and the earth as a source of pillage, making capitalism palatable to those by whom it might otherwise be threatened, and supplying it with a cultural and moral dimension that helps win it widespread acceptance.

For all the scepticism, critique and independence of mind it also encourages, higher education simultaneously creates compliant subjects who want to get ahead in the capitalist world, including in the very act of critiquing it.

Education, democratic control and climate action

That’s a paradox which everyone concerned about the future has an interest in resolving. But what does that mean for what should happen in the lecture theatre and seminar room in a society facing accelerating environmental collapse?

When it comes to constructing a liveable, sustainable world, no-one has all the answers. So democratic debate and decision-making, open to all perspectives, is essential to averting the worst effects of climate breakdown. Universities should be powerful models for this kind of democratic debate. But in order for them to become so, they will have to be released from the interests that currently distort them.

The fight for democratic higher education – free, open to all, under the democratic control of students and academics, unperverted by powerful corporate or political lobbies – is therefore integral to the fight for green economies.

That fight will have to be conducted politically, in a way that includes the whole of society. But part of it involves the abandonment of a powerful illusion among university workers themselves. This is the pretence that politics is something that happens off-campus – the illusion, or ideal, of the university as a neutral haven, the apolitical ‘community’ from which all major antagonism have been banished.

As academics, we often hesitate to admit how much our workplaces are, themselves, conflict zones with numerous fronts – most obviously, that between staff, especially casualised staff, and university management. Even if, in fact, we know that universities are traversed by numerous political conflicts, there is still a deeply-held belief among many academics and students that, fundamentally, we should behave as though this was not the case.

Yet a struggle for the climate is happening on campuses, now, and it is essential that it be seen as integral to academic work, and prosecuted intensely. On the most vital level, this means opposing, without compromise, those aspects of the university that directly fuel climate disaster: the laboratories whose research supports climate-destroying activity, and the intellectual and institutional infrastructure that support them.

It means challenging the investment portfolios academic organisations (including Unisuper) maintain in carbon pollution, and opposing the fossil fuel executives who sit on university governing bodies. It means persuading colleagues and students to participate in climate demonstrations and other activism, and not penalising them when they miss class to do so.

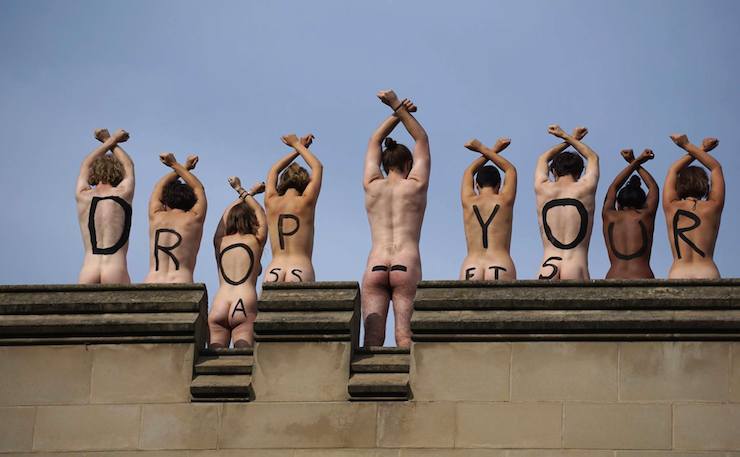

It means supporting student activists when they are punished by university administrations and their activism is repressed.

Smartwashing and disdain for activism

Whether over environmental or other questions, the humanities and the arts are apparently remote from the most concrete issues of political change. But even in these fields, academics have a role to play in favouring climate action. The very existence of the humanities –disciplines dedicated to ‘pure’ knowledge – poses a question highly relevant to climate politics: what is the connection between intellectual and ‘real’ life? What sort of knowledge and thinking do we need on a burning planet?

Humanities scholars spend a lot of time talking to students about ideas. Those ideas often, if not always, have a political dimension. But the risk is that, rather than politicising students, the constraints of the intellectual game – always being smarter, never being satisfied with an answer, always complexifying, always seeing what is wrong with a position – will end up stifling the impetus to choose a side and act, smothering them in indefinite qualification, hesitation and uncertainty.

Rejecting all political options as, in different ways, ‘problematic’ or insufficiently ‘sophisticated’ would be a highly detrimental ‘smartwashing’ of political inaction. Its only effect would be to reinforce the status quo. Academics must not act as though the ecological crisis is, in essence, an opportunity to demonstrate their powers of intellectual sophistication.

‘Climate’ must not become just the latest fashionable and ultimately trivial scholarly enthusiasm.

Quite the contrary: academics should state to students plainly that, no matter how far their understanding of the world and their capacity to see it critically are fostered at university, that on its own is not going to be enough. It is always possible to study, to complexify, to analyse problems more subtly and deeply. But if we continually postpone involvement in concrete action out of the belief it is not intellectually sophisticated enough, it will, simply, be too late.

No-one expects universities to produce revolutionaries, even if they are who we most need now. But political stances short of revolution are possible too – dissent, civil disobedience, disruption.

In the absence of a climate revolution, they are the practices that, at the bare minimum, will have to be fostered, and quickly, if our society is to claw back even a chance of surviving environmental collapse in a liveable form. Yet they are ones that universities talk about far less, rarely seriously, and often not at all.

Academics are more likely than many other liberal professionals to support grassroots politics. But many also have a distaste for activism, feeling that, as intellectuals or technical experts, they are intrinsically absolved from anything as messy and vulgar as personal involvement in it.

Risk-aversion, dislike of improvisation and uncertainty, the desire not to stray from the familiar ‘safe spaces’ of disciplinary specialisations: all these restrict academics’ conception of political possibility.

To compensate, academic culture has a tendency to overstate its own political relevance. We often see work in humanities disciplines described in terms that fundamentally misconstrue how it relates to political change. Rather than ‘fascinating’, ‘complex’ or ‘rich’, work has a tendency to be described as ‘required reading for everyone who cares about the climate’, ‘a desperately needed analysis’ or ‘a vital project’.

The trend is exacerbated by the norms of academic marketing in a system predicated on competition for research funding and media and academic prestige. Yet this framing damagingly intellectualises political action, suggesting that before political change can happen, we all have to go away and read up on the theory.

Even more academics willingly recycle the vague liberal clichés – ‘criticism’, ‘independence’, ‘scepticism’, ‘tolerance’, ‘pluralism’ – as the values of the education they oversee. If from time to time academics recognise, and ironically comment on, the triteness of these invocations in an education system disfigured by neoliberalism, we also often sincerely want them to be true, and sense that they contain, at least, validating half-truths.

But the reality speaks for itself: regardless of whatever ‘critical’ capacities higher education fosters in students, it has not blazed the trail for Western societies towards a future of democratic and environmental progress.

Instead, despite their significant internal political diversity, universities as institutions have deftly accommodated politics’ periodic swings between right and left, always careful to hold a balanced – ‘tolerant’, ‘pluralistic’, ‘critical’ – line, even as icecaps melt and forests burn. In a world where telling the truth about our situation is important, acknowledging this matters.

Insisting that ideas must be linked with action should be the watch-word of progressive education. Marx’s poles – interpreting the world and changing it – should be in a constant dialectic. If ideas and ideals actually matter, they should be given work to do in the world. This ambition is directly opposed to the philistinism that sees value only in ideas’ ‘relevance’ or economic utility. That enslavement of the mind to the market is part of the same movement which is precipitating humanities subjects’ ruin in tandem with the climate’s.

Letting ideas live

Students in the West are already, understandably, highly prone to depression. In an age of accelerating climate disaster, one way universities could help them is by showing that they are not greenhouses of apathy and quiet despair, asylums where thought is amputated from its most obvious consequences.

To defeat the ecocidal fossil-fuel lobby, and to counter the escalating threat of fascism that accompanies it, universities must not present intellectualism as though it was a kind of bourgeois charity – the thinker dispensing their insights to a waiting world like the executive gives a coin to a homeless person on the street.

What society needs is not thinkers, conceived as people who just think, but activists – people who think intensely, but whose thought is oriented to the possibilities of real change in a context of collective struggle; people for whom having a good idea imposes an obligation to collectivize it and try to make it active.

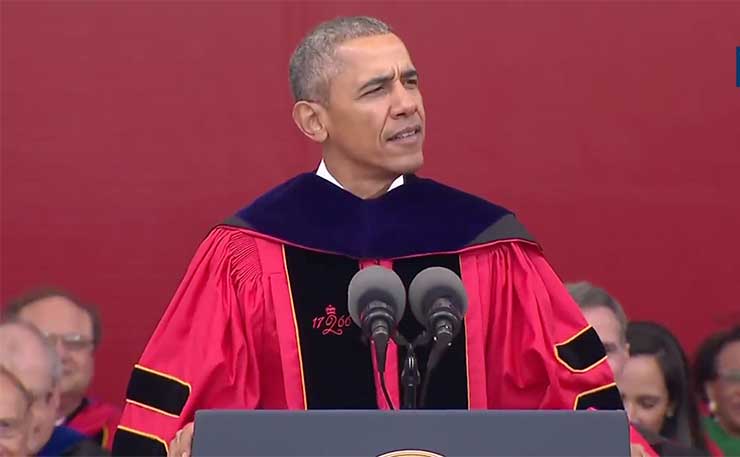

It’s no small detail that universities have produced the majority of the politicians whose decisions are now destroying the ecosystem and driving human societies centuries backwards. Many of the superintendents of today’s neoliberal, carbon-addicted order are highly educated, sometimes even cultivated, graduates of prestigious institutions.

Some heads of state, like Obama or Merkel, were even academics themselves. The environmental violence wrought by highly educated political leaders goes hand-in-hand with their crusades against social protections and attacks on democracy: French President Emmanuel Macron, who spent 11 billion euros in 2019 on subsidies to fossil fuels, is currently overseeing the most naked class warfare in recent French memory.

Since November 2018, Macron’s police have blinded 25 people in one eye, ripped off five hands, and caused 321 head injuries and two deaths, overwhelmingly among protesters against his austerity reforms.

Macron holds several postgraduate degrees, was a member of the editorial committee of the prestigious intellectual periodical Esprit, and worked as a research assistant for the philosopher Paul Ricœur. His violence to society is the image of the violence being done to the environment. It must not become a model of the role of intellectualism in a world of climate collapse.

More than ever, we are confronted with a choice between a radical transformation of our society and environmental and social breakdown – between socialism and barbarism. To limit the harm that unbridled capitalist production has inflicted on our planet, it will take more than pluralistic, critical and independent minds; it will take the collective intelligence of determined, confident and militant participants in social movements.

It is not just up to universities to produce them, but they should, at the very least, remove the numerous obstacles they currently place in the way of their emergence and validation.

There will be many times in the academic year ahead when the most important thing universities can do is get out of the way of their staff and students’ participation in determined climate activism – our only escape-route from an unliveable world.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.