DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

As we once again vacillate over the vexed question of Indigenous recognition, Australia’s multicultural society and house-of-cards economy are showing signs of fragility. Mike Dowson reflects on how risk and opportunity are linked.

Did you hear that kings rule by divine right? Or that a woman’s place is in the home? How about capitalism lifts people out of poverty?

All these have at some time been taken for plain facts. But they are not. They are stories, cognitive express lanes which lead to certain choices, behaviours and outcomes. They reinforce a social order in which some people benefit more than others. But stories can also serve higher purposes.

A Jawoyn man once told me the creation story of Leliyn. I don’t speak his language, and his English was limited, but his hands and eyes led me on a journey at the boundary of comprehension. Beside that lush oasis, its watery music flowing through me, the story harmonised my mind with the place. I understood then that Leliyn has been cherished and cared for by people for a very, very long time.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal, or you can click here to access our GoFundMe campaign.

Consider the effects of today’s dominant culture on the natural world. Melting ice caps, plastic-filled oceans, disappearing species and the squandering of finite resources hardly speak of good stewardship. We can point to the benefits we receive in exchange, but millions still live in poverty and die from preventable illness, even in developed countries.

What if we compared cultures based on protection of land and water for future generations? Only a robber baron could look admiringly on the poisoned mining landscapes and pustulant cities of Eighteenth Century Britain which supplied Australia’s penal settlements with prisoners. And we who followed must acknowledge the loss of soil, water and biodiversity which accompanied us.

Or what if we chose healthy relationships, the factor we now know is most important to human wellbeing? How would the early colony of downtrodden exiles and their tyrannical jailors running a rum racket compare with the society they dispossessed? And how would we justify, after the ransack of a continent, today’s grim statistics for youth suicide, mental illness, domestic violence and addiction?

The most dangerous myth is the idea of exceptionalism, that the present order is inevitable, superior or special. The West, Australia and indeed the current world order are all presently so endangered. Percy Shelley wrote a poem which illustrates how hubris is rewarded.

I met a traveller

from an antique land,

Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert…. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed;

And on the pedestal, these words appear:

My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

The Mystery of the Olmec

In the late 1850s, a few decades after Shelley wrote his famous poem, a farm worker clearing forested land on a hacienda in Veracruz, Mexico discovered a colossal sculpture of a human head. In subsequent years, another 16 were unearthed, as an ancient civilisation came to light.

Pondering these impressive relics, archaeologists posed the obvious question: what happened to the people who made them? Where did they go?

Over a century later, the writer Daniel Quinn observed that in this case, as with other great civilisations suddenly unearthed, there were people living nearby. He asked a different question: where did those people come from?

Most likely the Olmec didn’t ‘go’ anywhere. They stayed on their lands. But they stopped building the artefacts which announced them to posterity and resumed a simpler way of life, the rough blueprint for which had survived in cultural memory.

If we keep this thought in mind and look again at the known pattern of human civilisation, we can understand it not so much as continuous progress on a journey to us, as our self-congratulatory mythmaking proclaims, but as a long occupation of the Earth’s bioregions by its peoples, punctuated by a series of temporary experiments in large scale organisation and technological development, of which the present global order is the latest and most extensive.

Few of them lasted very long. Why should this one be any different? If we care about that, the pressing question of Olmec decline is ‘why’.

Pre-European Australia

One approach to this question is to compare with systems which endured.

There have been various reasons proposed over the years for why Australia’s First Peoples don’t count as ‘civilised’ – they didn’t settle in one place, they didn’t build things, they didn’t mount armed resistance and so on.

All are arbitrary to begin with, and all have been disproven. But in any case, they are all variations on the larger myth of terra nullius, defunct now in law, but persisting as a vague, inherited sense among settler society that the theft of an entire continent was justified.

We now know that many First Australians lived in settlements, some numbering thousands. They made large areas of land productive by conditioning Australia’s poor soils. The Brewarrina fish traps and the Pilbara rock art galleries are the oldest of their kind and among the most impressive and important of all human artefacts. But rather than damaging or degrading the landscape, or glorifying powerful individuals, these interventions strengthened human society’s interdependence with the natural world.

The astonishing places the colonisers ‘discovered’ and exploited were not some ‘natural’ bounty left untended, as the rapid decline in condition and yields that followed attests. They were fashioned by the patient genius of skilled custodians since before Northern Europe was occupied by anyone.

That these facts aren’t widely known and loudly celebrated by settler society is no reflection on Aboriginal people. That is a hallmark of domination by an alien culture, as are blights like deforestation, soil degradation and biodiversity loss. A society can’t conceive of ‘success’ as thousands of generations of wise stewardship while its measure is current year profits. Such a society has yet to take root.

The cultures of Indigenous Australia represent Earth’s longest continuous civilisation. They are the only people to have preserved in cultural memory a transition between geological ages. The emergence of the benign Holocene, which gave the Great Barrier Reef its dramatic present morphology, appears in art, dance and story. As a new, more difficult geological age threatens the Reef’s survival, along with our own, this fact alone should be of interest.

By almost any measure, including those settlers applied disingenuously to justify dispossession, Aboriginal Australia was highly successful. Historians from Henry Reynolds on have shown that what gave Europeans the upper hand was a propensity for genocide that was officially tolerated, and occasionally sanctioned. Some was inflicted by superior weaponry, the rest by land transformation, alcohol, imported diseases and later programs of assimilation.

The only war we know was fought on Australian soil was the frontier war. Although there are no ‘official’ statistics, it likely incurred more casualties than any other conflict. Yet, amid all the fanfare attending our service to the British and American empires, this one is ‘missing in action’ at the Australian War Memorial. That speaks volumes about our prescribed national identity.

It’s true there was violent conflict in Aboriginal society, and high infant mortality, as there was in almost every society on Earth at that time, and among the settlers. We cannot retrospectively ascribe the benefits of 230 years of subsequent advances by the peoples of the entire world in law, diplomacy and medicine to the First Fleet, as if they brought that in the cargo hold.

Nor can we credibly measure the value of Aboriginal Australia using an alien system ruthlessly imposed, although this makes the undeniable achievements of our Indigenous people even more remarkable. And yet these biases are central to our myth of modern Australia.

That myth blinds us to historical atrocities, present failings and the enduring value of Indigenous wisdom. It’s neither scholarship, nor justifiable cultural pride. It’s the same unquestioning racism which locks Aboriginal disadvantage into every aspect of contemporary Australian life and perpetuates failed paternalistic policy development.

I was at a conference in Old Parliament House when the Uluru Statement from the Heart was rejected offhand by our then Prime Minister. Several Indigenous academics were present, but the blow was felt by everyone there. A statement of profound reflection, the product of a long, meticulous endeavour of consensus among diverse peoples in a spirit of optimism and goodwill, was simply tossed aside as worthless. There could have been no greater expression of the contempt which derives from ignorant privilege.

This continent is at terrible risk from a changing climate. We are fools not to turn to the cultures which flourished here through a glacial period and subsequent warming and co-created some of the most magical places on Earth. The Indigenous Rangers provide a glimpse of what’s possible.

What is modern Australia’s problem?

Surely a limitation can be found in our mythology. The dominant culture has an idea of ‘us’ as something non-Indigenous, which we call ‘Western civilisation’. Scholars usually mean by that a system of cultural practices, organising principles and institutions which developed out of the fertile crescent via Athens, Rome, Christianity and the Scientific Enlightenment.

But most Australians have little more tangible contact with the depth of that tradition than they do with the ancient cultures that preceded it. Who among our public figures stands as its exemplar? Our daily experience is of a facile machine for acquiring private property and maximising personal consumption which will sacrifice any principles and institutions when expedient. It gives us ‘factory’ farms and ‘smart’ phones and ‘reality’ TV. Having all but exhausted this planet, we now speculate about populating others. Then we dream of engineering our own immortality.

Who is the ‘we’ in this story? It’s not a people. It’s a way of life which is separative, acquisitive and exploitative. It’s the identity of the coloniser. It valorises wealth accumulation while it squanders a heritage of great beauty and significance, both cultural and material, Indigenous and European, for toxic waste, mountains of garbage, degraded land, damaged waterways and social problems festering in agglomerations of miniature private ‘homesteads’.

Naomi Klein observes it’s the big frontier settler states and their former colonial masters which exemplify this syndrome. The US, the UK and Australia presently demonstrate how incapacitating it can be in challenging times. But global capitalism adds scale and risk. The colonial project never finished. Instead it became planetary. It is the self-image of affluent people worldwide in the Anthropocene, even those who abhor it, who often believe it’s ‘human nature’ which dooms us to extinction. Australians with roots in other places were absorbed by it when our embattled forebears lost their own traditions and homelands to earlier waves of it.

This myth is destined for retirement. The only question is how big a dose of reality is required.

Ungrounded in care for the Earth and its peoples, technology is a loose blade flailing in darkness. What more evidence do we need than the collapse of the natural systems on which we depend? Martian colonies are ideas. Crop failures are real. Undressed of our mythology we are like apes with power tools playing at divinity.

Enduring cultures practice humility and prudence. The West, and by extension the present global order, are like the Olmec. Our grand experiment has produced wonders and transformed our planet, but its weaknesses are now tumbling into view as environmental disaster and societal decline. The great risk is that we may have lost the capacity for self-effacement and forgotten our blueprints for alternative ways of living. In that case, we are barbarians in waiting.

Australia is in a special kind of trouble. We carelessly betrayed the transformative sacrifices of our visionary forebears. We became addicted to easy money from foreign trade and local bubbles and threw open the doors to commercial rapine. The circumstances which rewarded short-term thinking are at an end. There is no viable substitute now for principled governance.

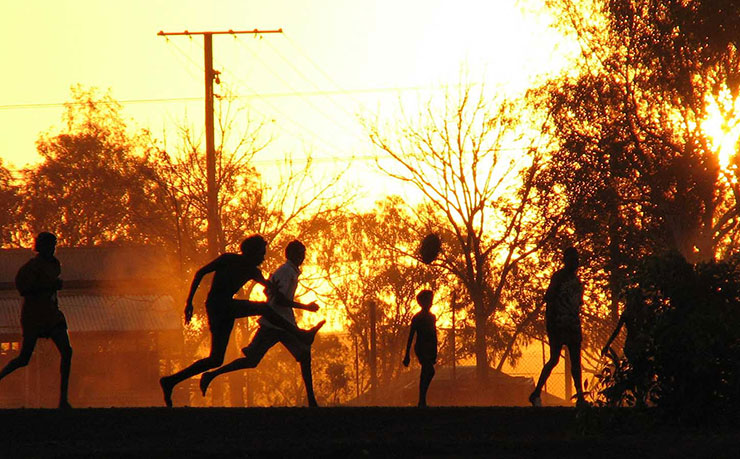

But we have another opportunity. Wherever we came from, we’re all here now. There’s no reason blackfellas and whitefellas and any other fellas need to be at odds. Our combined strengths outweigh our separate differences.

Here the oldest of human societies cohabit with traditions from around the world within a framework of democratic institutions. What unites contemporary Australians is neither Christianity, nor science, nor capitalism. It’s the urge to be free from oppression and live in peace with one another and the natural world.

Why else do people from so many different backgrounds seek to come here? And what else are the voices of protest from across the political spectrum seeking to achieve? Millions of First Australians shaped a continent for human flourishing, millions of immigrants made it famous as a land of opportunity, millions here today want to keep it that way, and millions missing out just want to be included.

There is no conflict in that. How can people wanting the same thing be in conflict, unless there isn’t enough to go around? And how can there not be enough to go around for a population our size, unless we allow the poisonous infusion of greed and malice to destroy community and country?

The people who wish to divide us can never have enough. They are beset by the dream of conquest and exploitation. They think like plantation owners harvesting wealth and privilege from fields of misery. Their tools are the standard equipment of unjust power – captive institutions, systemic violence and mob fervour marshalled in service to tribal identities. Around the world, they coax from troubled populations the psychology of the lynching party.

It isn’t humankind that’s doomed to extinction. It’s that way of life. But we must ensure it doesn’t take us all with it.

If we dare to look above the grim, contested ruts of the colonial past, not in denial, but with the strength and confidence that come from understanding, our already shared purpose can direct our technology and resources through bioregional initiatives toward a prosperity which is inclusive and protected by awareness of deep time.

That is the possibility which awaits us on the other side of true reconciliation.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal, or you can click here to access our GoFundMe campaign.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.