DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

The anger over Extinction Rebellion protests is more about the cause than the commotion, writes Jeff Sparrow.

“We note that the … campaign is more than an expression of legitimate dissent and protest. It is… designed to inconvenience thousands of citizens and to subject community life to dislocation. It is a wholly unjustifiable claim of right which amounts to an unjustifiable denial of the rights of others.”

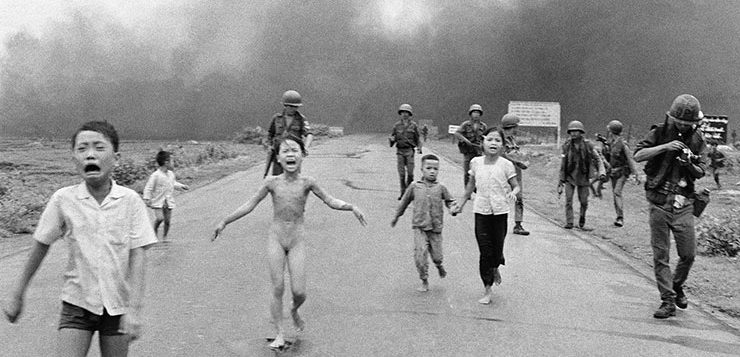

That statement by government MPs might have been written in response to Extinction Rebellion’s recent week of action. But it wasn’t. Actually, it was published in May 1970 in relation to the famous Vietnam Moratorium.

Almost every charge leveled against XR over the last few weeks was also made against Vietnam-era activists, especially after Labor’s Deputy Leader Jim Cairns told the press of protesters’ plans for a symbolic 15-minute sit down in the central business district. His call, in particular, for marchers to “occupy the streets” prompted a media meltdown not unlike the one we witnessed last week.

Infamously, Billy Snedden described the moratorium participants as “political bikies who pack rape democracy” while Prime Minister Gorton declared that Cairns represented a “policy of anarchy”.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal, or you can click here to access our GoFundMe campaign.

Then, as now, the involvement of high school students in the protests fostered particular conniptions, with BA Santamaria (Tony Abbott’s mentor) calling for teachers who “manipulated the children of others for political reasons” to be sacked by the government.

The Adelaide Advertiser expressed the mainstream consensus in an editorial that again sounds remarkably contemporary.

“To suggest that a city’s traffic be brought to a stop,” it wrote, “schools closed, industry paralysed, shops and offices shut, and that, in effect, mobs take charge in the streets, is to show a dangerous leaning to violent and disruptive measures.”

The success of the Moratorium, not just in mobilizing huge numbers of people but in shifting attitudes on Vietnam (a war now almost universally recognized as a criminal debacle), helped normalize protest in Australia.

In the years since then, political marches became so unexceptional as to lose most of their newsworthiness. In 1970, it might have been credible to denounce a 15-minute street occupation as the first step to social breakdown. But in the decades that followed, such claims sounded increasingly outlandish.

That’s why the response to the relatively small and carefully managed protests organized by XR over the last week was so extraordinary.

Peter Dutton, for instance, seemed to be channeling – God help him! — Billy Sneddon.

“These people aren’t protesters, they’re anarchists,” he said of the XR protesters. “They don’t believe in democracy, they don’t believe in our way of life.”

For obvious reasons, the call by Kerri-Anne Kennerley for activists to be run down by cars or incarcerated without food drew the most attention. But, in some respects, her remarks were less significant than those made by ostensible progressives.

Take, for instance, the comments by Jenny Mikakos, a representative of the Labor left and a minister in the most leftwing state government in Australia. Mikakos told told the media that protesting was “a fundamental part of living in a democracy” – and that, indeed, that she’d done it herself.

But she immediately added, “But we need to ensure also that when people are protesting that they’re not disrupting the wider community.”

Compare that to the defence Jim Cairns offered of the moratorium back in 1970.

“The weaknesses of Parliament have been widely recognized,” Cairns said. “They will not be cured by accusations of anarchy and mob role whenever anyone decides to do something about it. Democracy is government by the people, and government by the people demands effective ways of showing what the interests and needs of the people really are. It demands action in public places all around the land.”

For Cairns and the moratorium marchers, protests were a fundamental part of democracy not because they didn’t disrupt the community but because they did. It was precisely the challenge that the moratorium posed to the status quo that made it important and worthwhile.

For Mikakos, by contrast, protests are purely a matter for the individual, legitimate only so far as they don’t impinge on choices by others.

The comparison illustrates Labor’s shift away from the older traditions of social democracy to the neoliberal perspectives of a marketized age, where you have a right to demonstrate but only if your demonstration doesn’t affect anyone else in the slightest.

In 1970, Jim Cairns-led rallies. In 2019, the Queensland Labor government responds to them by embracing Bjelke-Petersen-era anti-protest legislation and calling for the imprisonment of activists.

Yet it’s also worth noting the particularly anomalous treatment accorded to XR.

After all, despite the long decline of the Left, protests that, in Mikakos’ words, “disrupt the wider community” still take place with some regularity.

During the recent federal election, for instance, her Labor Party gave its support to the ACTU’s ‘Change the Rules’ rally in the Melbourne CBD in April this year. That event, attended by perhaps 100,000 people, caused far more disruption than any XR protest – and yet Labor’s Daniel Andrews spoke to the assembled crowd.

Likewise, a few days ago, a small group of anti-abortion bigots staged a rally in the same city. The police created a cordon around them to facilitate their protest – and, as a result, disrupted city traffic.

Yet we didn’t see any of the hysteria that accompanied the XR actions.

Across Australia, the various capital cities close down in whole or in part for all kinds of reasons, ranging from Anzac Day parades to football finals to artistic events like Melbourne’s White Night.

And, by and large, no-one bats an eye.

So what makes XR difference? It’s a question not simply of tactics but of goals.

In a sense, climate change allows no half measures. If you believe the scientists, you either commit to a fundamental shift in humanity’s relationship with nature – or you prepare for a planet permanently devastated by inaction.

The inconvenience of climate protests – even the relatively small-scale actions we’ve seen so far – necessarily confronts politicians and the public with that choice. The minor disruption they cause provides a reminder of the almost unthinkable disruption threatened by global warming and the utter failure of governments to respond to it.

If you dismiss the XR rallies as wilful chaos created by attention-seeking misfits, you can remain sanguine about what the future holds. If you don’t – if you accept that the protests have a purpose – you’re forced to confront the tremendous challenge that lies ahead.

BE PART OF THE SOLUTION: WE NEED YOUR HELP TO KEEP NEW MATILDA ALIVE. Click here to chip in through Paypal, or you can click here to access our GoFundMe campaign.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.