The world’s second largest nation has targeted for eradication the world’s largest environmental organisation, all in the pursuit of profit and growth. Ruchira Talukdar explains.

That Greenpeace is no friend of governments is a widely accepted fact. When it comes to governments of industrialising nations, this friction between combative environmental activism on the one hand and the politics of anxiety around development on the other can cost an organisation its right to function.

Greenpeace has been struck two big blows in the last four years that threaten to wipe out its existence in India.

In 2014, the Modi government stopped Greenpeace India from receiving international funding. Even though the global organisation explicitly states it does not accept donations from corporations, the Indian government deemed its funding pattern to be opaque on account that it collected donations in small amounts from persons of different nationalities located all over the world.

The organisation’s Indian arm recovered on the strength of its local fundraising, although it was forced to reduce staffing and cut back on various campaigns.

This January, Greenpeace shed two-thirds of its advocacy staff, shut two campaigning offices and wound up most of its nearly two decades long activism work in India. The immediate circumstances that led to the near closure were unexpected raids on Greenpeace last September by the Enforcement Directorate, an enforcement agency under the Ministry of Finance.

All of Greenpeace’s accounts were frozen on account of alleged violation of India’s draconian Foreign Contribution Regulations Act (FCRA) 2010. The Ministry of Finance claimed that Greenpeace continued to receive foreign funds through the Direct Dialogue Initiatives India, its quasi-independent fundraising arm, and that the organisation had set up a mechanism for receiving domestic donations so as to mask the real sources of its income.

Greenpeace India appealed to the High Court of Karnataka where it is based and was allowed to withdraw $100,000 towards staff salaries upon payment of an equivalent bank guarantee. This expensive course of action proved unviable beyond a couple of months and Greenpeace was forced to stop most of its advocacy-based work in India.

Although the High Court has just ruled in the organisation’s favour, asking the Enforcement Directorate to unblock the twelve accounts, it remains to be seen whether this blow proves to be the last straw.

Immediately after assuming office, the Modi government targeted Greenpeace’s climate campaign that focussed on coalmining and thermal power generation. Labelled ‘anti-national’ for opposing coalmining in the Mahan forests in Central India, its accounts were frozen twice in the same year by the Ministry of Home Affairs, its licence to operate revoked, and one of its activists was barred from travelling overseas to speak about atrocities on indigenous Adivasi communities in coal-rich areas. The government actions against Greenpeace started after reports by India’s Intelligence Bureau (IB) singled out Greenpeace as a ‘threat to national economic security’.

These intelligence reports on the activities of NGOs that threatened to pull India’s GDP down by 2-3 per cent were prepared under the previous Congress-led coalition government, but strategically leaked to the media during the initial months of the Modi government.

But since the fight for Mahan and the consequent government crackdown, Greenpeace’s Climate and Energy campaign has built a collaborative network of public campaigns around air pollution and decentralised solar projects. One is a burning health problem and the other a present and future need, but both tangentially tackle the problem of coal and are evidently less controversial. So what might be the political imperatives behind this second attack on Greenpeace?

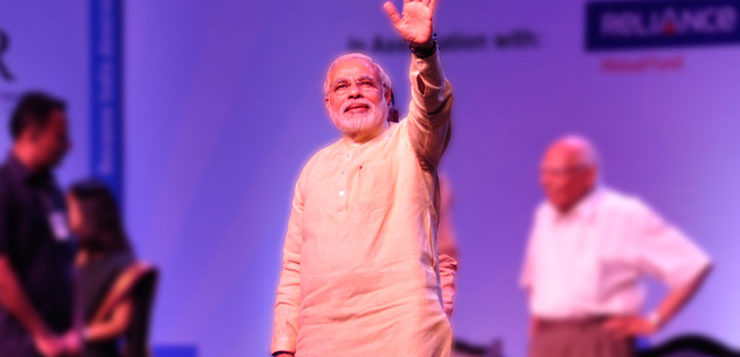

The Greenpeace staff members I spoke to pointed to the broader atmosphere of intolerance to dissent under Narendra Modi, whose dislike for NGOs is well known. During his first six months Modi oversaw the mass cancellation of licences for NGOs to receive foreign funds even as he amended legislation to further facilitate the channelling of foreign funds to political parties.

With only two months left for India’s general elections, critics point to a similar pattern of intolerance as in the initial months. The simultaneous crackdown on Greenpeace and Amnesty, two rights based international NGOs, came close on the heels of the arrest of civil liberties activists which received heavy criticism as a ploy to divert attention from various unaccountable actions by the government.

Greenpeace India’s outgoing Climate and Energy Program Manager Nandikesh Sivalingam – he is one of the many staff members who are leaving after the recent crackdown – explained during a phone conversation that the enforcement directorate’s raids at the Greenpeace and Amnesty offices in Bangalore occurred when the media was busy scrutinising the controversial Rafale aircraft deal with France (it has been alleged the Modi government blatantly favoured a private corporation over India’s public sector aircraft manufacturer).

As an international organisation Greenpeace can often attract unsolicited attention, or worse, end up as collateral damage for the government’s ire at society’s dissent. Even though its latest campaigns had not courted like its anti-coal protests, Greenpeace still served as a convenient target to practice the well-rehearsed narrative of fear and repression.

It is worth looking at Greenpeace’s two decades’ of activism in India to understand how the frictions between this international body and the Indian state escalated across changing economic and environmental realities to finally culminate in its near eradication.

Two decades in environmental debates

Greenpeace officially registered in India in 2001, although India-based volunteers had staged protests around toxic waste dumping in the 1990s. With governments oversensitive to the notion of ‘western’ interference in India’s development, the ‘foreign tag’ worked to the organisation’s detriment from the very start.

Greenpeace’s first attempt at an Indian registration in 1997 proved unsuccessful after it flew a hot air balloon captioned ‘Nuclear Disarmament Now!’ across the Taj Mahal in Agra. One of its earliest campaign successes that drew international headlines came in 2006, when a global Greenpeace action forced France to recall the decommissioned warship Clemenceau bearing high levels of asbestos. The toxic ship was headed for scrapping at the world’s largest ship breaking yard at Alang in Gujarat on India’s west coast.

With the memory of the Bhopal tragedy still alive and its inter-generational impacts still playing out on communities around the epicentre of the gas spill, Greenpeace strategically inserted itself into the public debate with campaigns around toxic pollution by foreign corporations.

In collaboration with local groups and the workers union, Greenpeace succeeded in closing Unilever’s thermometer manufacturing plant in the southern hill station of Kodaikanal. This action came after public interest groups exposed high levels of mercury contamination from the dumping of broken thermometers in protected forests adjacent to the factory. Unilever had shifted its thermometer manufacturing to India from New York, where it had failed to comply with US regulations.

Greenpeace’s confrontational activism towards corporations and governments, combined with its global reach and a variety of tactics professionalised over time and across geographies helped it form linkages with local groups to tackle ongoing environmental challenges with fresh perspectives. If its early successes in India tackled a particular fallout from globalisation – the international trail of hazardous substances and making third world countries ‘a waste dump’ for the first world – its subsequent campaigns asked questions that were intricately linked to India’s developmental paradigm.

During the first decade of the new millennium, the effects of India’s economic liberalisation that allowed private and foreign investments across various sectors started playing out with full effect.

Greenpeace’s advocacy often served to reframe debates on contentious environmental issues during this phase of India’s neoliberal economic growth. Greenpeace India’s campaigns against genetically modified (GM) crops came under the government’s radar for challenging the official rhetoric of “food security” and “scientific progress” in agriculture. However, in the midst of various public controversies and debates around the safety, transparency and yield benefits of GM crops, successive Indian governments have by now placed moratoriums both on commercially growing GM food crops such as Bt Brinjal and further field trials.

With international climate change dialogue progressing along a parallel time-track to India’s economic boom, publicly contentious energy projects such as in India’s nuclear sector were presented as both ‘environmentally benign’ and ‘economically viable’ options to “meet the increasing electricity needs of the country”. Alliances and networks of various groups, Greenpeace included, that sought accountability for risky and secretive projects such as the Kudankulam nuclear power plant on India’s southern coast met with harsh repressions which extended to arrests on account of ‘waging war’ against the nation, filing of ‘sedition’ charges, cancellation of foreign donations licences, travel bans and prohibiting journalists from visiting protests sites.

In 2010, India enacted the Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Bill (Nuclear Liability Bill). The Act was the necessary last step before the Indo-US civil nuclear agreement that would allow private nuclear companies into the Indian market could become operational. The initial bill indemnified suppliers from all costs of accidents, and also denied citizens the right to sue for compensations. Keeping Bhopal – one of the world’s worst environmental disasters – in mind, the thrust of civil society’s advocacy around the bill before it reached the Upper House was to make sure corporate liability was not capped. This would prevent private American suppliers from getting off “scot free” in case of an accident. Greenpeace’s collaborative advocacy and its public mobilisation succeeded in including a compensation package comparable to that in the US and in holding suppliers liable for accidents.

Nuclear power remains a highly political issue in India owing to the fact that Bhopal still shapes public discourse around ‘foreign’ corporate accountability. The setting up of private atomic energy projects therefore generates spirited opposition.

Coal on the other hand enjoys a central place in India’s energy development, meeting 60 per cent of India’s electricity needs and consequently making it the hardest to argue against.

Greenpeace’s anti-coal advocacy in India took a circuitous route to its recent protests in Mahan. In the earliest stages, Greenpeace’s climate advocacy focussed on improving energy efficiency by phasing out incandescent light bulbs. The ‘Ban the Bulb’ campaign succeeded in triggering a consumer focussed government subsidy scheme to replace inefficient light globes with compact fluorescents in 2009.

The bigger rationale for reducing coal-based emissions to tackle climate change was harder to establish in the public realm, owing to India’s post-colonial developmental paradigm. Asserting India’s sovereign right to grow for the sake of a better standard of living for its impoverished people, former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ‘famously’ said at the Stockholm conference in 1972, “Are not poverty and need the greatest polluters?”

India’s early position on climate change reflected this ‘developmental justice’ approach, and demanded significant reductions from ‘historically responsible’ economies while leaving developing nations the ‘carbon space’ to grow. Civil society groups broadly sympathised with this North versus South, rich versus poor binary in global accountability, as articulated by successive Indian governments.

Poor as cover

‘Hiding Behind the Poor’, a humanitarian report by Greenpeace on climate impacts in India attempted to ‘recast’ the ‘gaze’ of climate injustice away from the global divide and towards the country’s glaring economic inequality and consequently emissions footprint.

“The considerably significant carbon footprint of a relatively small wealthy class (1% of the Indian population) is camouflaged by the 823 million poor who keep the overall per capita emissions below 2 tonnes of CO2 per year”, the report found, based on face to face surveys of households across income classes.

Released months before the 2007 Bali UNFCC Summit, its main arguments sparked a controversy regarding India’s own commitment towards intra-generational equity for the Indian poor who will bear a ‘disproportionate’ climate burden.

More than a decade from Bali where global negotiations for post-Kyoto commitments began, and four years since the Paris climate accord, the climate predictions for the Indian subcontinent are dire. The authors of the Indian IPCC chapters have pointed to the increasing vulnerability of coastal, low-lying and high mountainous regions in the country, as well as extreme heat stresses and degraded air quality in cities. They underscored that the burden of climate change will fall “disproportionately on the poor who are not responsible for the problem if we do not meet the 1.5 degree target”.

India subsequently adopted an action plan on climate change (NAPCC) ahead of the Copenhagen Summit in 2009. The national policy document, which brought much needed focus and definition to various civil society organisations in relation to India’s contribution to mitigating climate change, identified the ‘co-benefits’ approach to India’s economic growth. Essentially, the NAPCC policies would allow India to maintain a high growth rate to ‘increase the living standards of a vast majority’ in order to reduce their ‘vulnerability to the impacts of climate change’ while simultaneously making this development path environmentally sustainable.

The document identified eight initiatives, defined as ‘missions’, for mitigating and adapting to climate change, prominent amongst which were solar, energy efficiency, water, sustainable agriculture and ‘greening India’.

Rapid renewable growth

Ten years later, India’s rapid growth of installed renewables capacity stands globally recognised. Ahead of the Paris Summit, India committed to sourcing forty per cent of its electricity from low-carbon sources by 2030, aiming for an emissions intensity reduction of 35 per cent from 2005 levels. India’s Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDC) submitted to the UNFCC did not specify when its emissions would peak, underscoring its international position of not constraining critically needed economic development.

This so called ‘balanced’ approach to economic growth – increased use of both coal and renewables – is exemplified by the fact that while the government prides itself on keeping ahead of its Paris targets, India’s emissions increase has kept pace with GDP growth in the last decade, making it the fourth biggest emitter after the EU. Hence also, while the Modi government intends to more than double India’s renewables installed capacity from 71GW to 175GW by March 2022, it also aims to double coal production by 2020 in a bid for energy security.

India’s Paris submission offers some crucial statistics: India houses the largest proportion of global poor at 30 per cent of its population. Over 300 million Indians (24% of the population) live without electricity access. That ‘no country in the world has been able to achieve a Human Development Index of 0.9 or more without an annual energy availability of at least 4 tonnes of oil equivalent per capita’ stands strongly highlighted in the document.

India’s human, economic and political priority of providing electricity to the literally powerless millions, mostly in remote rural locations, cannot be denied.

The notion of electricity use is strongly linked to overall development and the improvement of specific indicators such as child mortality and female life expectancy in the Human Development Index. This is where its coal-energy base remains crucial, and India continues to assert its need to ‘work for economic progress towards a secure future for its citizens’. But there is a catch to this historic assertion in the present times.

Then comes neoliberalism

Liberalisation of India’s economic policies since the 1990s and the privatisation of electricity production, previously a sole state preserve controlled through the government companies Coal India Limited and National Thermal Power Corporation, has ruptured the thinly-veiled logic of ‘greater common good’ from industrial development that prevailed in a characteristically socialist India.

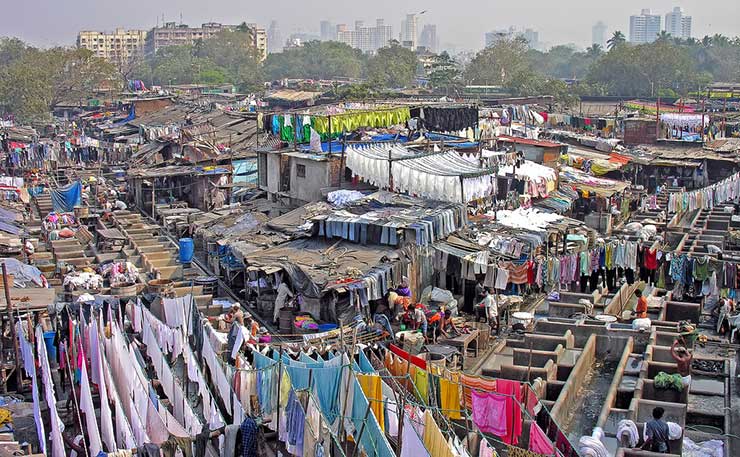

In a highly unequal society like India, state-led industrialisation projects, while benefitting the urban elite and middle classes, have displaced an estimated 60 million Adivasi and peasants with ancestral ties to their lands since independence. But with neoliberalism from the 1990s, the state assumed the role of a ‘land broker’, securing Adivasi lands for private corporations, making its corporate bias over the interests of affected communities starkly evident and raising fundamental social justice issues.

The gap between expectations and results from economic transformations in the multifarious Indian context became evident within a decade, most tellingly in Gujarat, hailed as the poster child of India’s neoliberal economic growth.

In Narendra Modi’s state, a focus on concentrated investment largely in private resource extraction neglected vital sectors like agriculture and failed to improve social and developmental indicators. Ultimately, India’s high growth, precariously balanced on a narrow alliance of economic and political elites, did not lead to a corresponding reduction of poverty.

A question pertinent over seven decades of post-independence-development – who benefits and who misses out from coal-centric high economic growth – has by now assumed criticality.

Against this backdrop, Greenpeace’s ‘controversial’ anti-coal campaign in the virgin Sal forests of Mahan in Central India in 2014 tackled the coal problem at various levels: the humanitarian, the political and economic, and the environmental.

Mahan is the last remaining contiguous track of old growth Sal forests in one of India’s biggest coal-industrial complexes in Singrauli district, Madhya Pradesh. It is a prominent tiger habitat and elephant corridor, and home to Adivasis. After economic liberalisation, the possibility of five super-sized power generation projects requiring an estimated 10,000 acres of land, raised the spectre of a third wave of displacement for forest-dwelling communities.

Side by side with Greenpeace, a mass rising of twelve villages opposed the mining of ‘Mahan’ coal-block in the Mahan forests that threatened to fell five million Sal trees and affect 50,000 forest livelihoods. The mining was to be undertaken by London Listed Essar Energy in partnership with Hindalco, an Indian private operator.

Forest-dwellers found a legal voice for their historic land rights through the newly enacted Forest Rights Act 2006 (FRA), which, inspired in degrees by the New South Wales Land Rights Act, aimed to return ancestral lands to India’s Adivasis who have faced dispossession since the British colonial times.

The FRA contains a provision to veto mining. The first legal success through the FRA came when the Dongriya Kondh of Odisha overwhelmingly vetoed bauxite mining on their sacred forested mountain, Niyamgiri. Variously referred to as ‘India’s first environmental referendum’ and one of the finest examples of ‘democracy at the grass-roots’. The Dongriya Kondh’s resistance energised other land-fights and the people of Mahan filed for forest rights and vetoed mining through village councils.

Other twists including the country’s highest court declaring that 204 coal blocks (including Mahan) had been allocated in an “ad-hoc and casual manner” by the previous United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government and the Modi government cancelling mining in Mahan led to a ‘victory’ for the people of Mahan.

They marked the successful culmination of a four-year struggle as ‘Democracy Day’; a photo of leaders in the local fight holding a large yellow banner captioned “Democracy Zindabad” meaning long live democracy in Hindi, captured the very essence of the joint resistance.

The movement in Mahan became acutely aware of their constitutional rights and questioned India’s developmental paradigm that pitted two notions – one of ‘economic progress’ and the other of their claim over ancestral forestlands and traditions – against one another.

Greenpeace ’s first mission in Mahan, long before the movement rose up, was to build understanding about the community’s rights over forests through the FRA. Based on a survey of various villages, the Greenpeace discussion paper Countering Coal? described the indispensability of the Mahan forests to the indigenous way of life, from the commercial harvesting of Mahua flowers and Tendu leaves, to the use and knowledge of various fruits, roots, herbs, wood, flowers and leaves.

Known as an issue-based campaigning organisation, grassroots groups remained wary of Greenpeace, expecting it to beat a ‘hasty retreat’ leaving communities vulnerable after a ‘strategic win’. Networks such as the National Association of People’s Movements have deep roots in the subcontinent, and stretch as far back as the pre-independence Gandhian era. Leaders often stand ideologically opposed to professionalised and foreign funded NGOs. But after a visit, Anurag Modi from the Madhya Pradesh based Peoples Resistance Movement felt that Greenpeace’s work in Mahan told a different story since; it had actually organised a movement of affected communities.

This constitutes part of the reason why civil society overwhelmingly supported Greenpeace during its crackdown in 2015.

Growing support

In 2015, simultaneously with a momentous victory at Mahan, Greenpeace faced the prospect of being obliterated. The whole issue came into the media glare when Priya Pillai was deboarded without warning from a London bound flight. She was scheduled to testify before the UK’s joint parliamentary committee about mistreatment of Adivasis in Mahan by Essar Energy.

The government claimed in its affidavit to the Delhi High Court, where Ms Pillai had filed a writ petition appealing the offloading, that allowing Priya to depose would have hampered foreign direct investments, and risked trade sanctions.

Pillai’s statement, if written into foreign policy by western governments, would “subdue India’s increasing strength on global platforms”, the government alleged. The government made an example of a Greenpeacer as a ‘bad activist’ while commending movement leaders such as Medha Patkar (who led the resistance against dams on Narmada) for never deposing before ‘a foreign committee’.

Ms Patkar refuted the government’s claim – she had in fact appeared before the US Congress in 1989 – and other prominent activists condemned the obvious attempt to ‘confuse the issue’.

In its bid to expose “the true cost of coal, which is not just economic but also environmental, social and spiritual”, Greenpeace found a final line of defence in India’s court system. In a precedent setting judgement for activists questioning economic growth at any cost, the Delhi High Court ruled on 12th March 2015 that “contrarian views held by a group of people (who form a nation) do not make them anti-national”.

The judge was referring to Ms Pillai’s views on the impact of coalmining in Mahan. In January that year, the same court had directed the Ministry of Home Affairs to unblock Greenpeace’s foreign accounts, ruling that the crackdown was “arbitrary, illegal and unconstitutional”. And in May that year, for a third time, the Delhi High Court directed the government, which in a vindictive bid had frozen all of Greenpeace’s accounts, both foreign and domestic, to unblock the domestic funds.

The organisation acknowledged the verdict with relief, and paid staff salaries owed for months. It filled a football field with a giant banner captioned, “You cannot muzzle dissent in a democracy” to register its protest and survival despite the odds. Greenpeace had won against the ‘Union of India’, even if momentarily.

But the comfort was short-lived. Greenpeace once again found itself in the same financial rut late last year. This time, acting through the non-descript Enforcement Directorate, the government of India avoided making Greenpeace’s incarceration a high-profile public issue.

Greenpeace found itself teetering on the brink of obliteration on December 10 as activists marched as part of mass-commemoration of 70 years of the UN Declaration of Human Rights that upholds the right to freedom of speech. And in January, the lights dimmed out at Greenpeace as it shrunk its Indian campaigns to a fifth of its capacity.

From environmental to human rights, Greenpeace India’s story

From its beginnings as a group of hippies out in the high seas in zodiacs to stop whale hunts and bearing witness to nuclear testing in Amchetka, to organising Adivasi communities in the coal-rich forests of India is a far stretch for the imagination. It speaks to the diversity of Greenpeace’s activism across the globe and its ability to transform over the decades and changing modes of challenges, particularly after the advent of climate change.

Skirmishes with corporations and the government aside, Greenpeace’s two decades in India have not been without ideological and practical contestations with the broader civil society network.

A widely held view about the organisation’s “intransigence” makes its collaborators in India wary of its ability to nuance messages to the intricacies of this society’s contexts. In this regard, the most recent case is Greenpeace’s stand on coal, variously expressed through attributing catchy epithets and concocting catchy slogans: “Quit coal”, “Keep it in the ground” and “Say no to fossil fuels”.

Indian civil society’s response to Greenpeace’s “jump out there” statements must not be confused with the government’s proclivity towards punitive measures for groups that question India’s energy complex, and ‘foreign funded groups’. Collaborators on the other hand chafe at the black and white nature of the organisation’s positions, its ‘one-size-fits-all agendas’ which at face value betray a lack of reason, perhaps even a disregard for various justice contexts across the world.

Whether Greenpeace’s seeming unreasonableness helped or hindered India’s human-rights-centric-environmentalism will remain an open-ended debate. Priya Pillai said during an interview after the offloading that “having worked with many organizations, (she) found that Greenpeace didn’t shy away from taking a stand on issues; it wasn’t scared of anybody”. Final cues for this debate can be drawn from Mahan.

I visited this forested corner of an otherwise coal-blighted landscape in Singrauli in March 2017. Even though it was peak Mahua gathering season and the woods outside the hamlets were carpeted with clammy yellow flowers, men, women and children had turned up in hundreds to celebrate the second anniversary of their victory over mining.

There was a certain spirit about the local movement as oft-used slogans from the prime years of protests were shouted in chorus under the billowing tent top, even as hot loo blew outside; the spirit felt a lot like dissent.

The chronology of the resistance movement is highly demonstrative of India’s unique theatrics of crony capitalism and corruption within the ranks. The struggle-years spanned the coal-scam plagued last leg of Manmohan Singh’s United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government, and the first year of Narendra Modi’s authoritarian government, with its mission of shortening environmental clearance times for ‘ease of doing business’. These government malaises directly impacted people at Mahan.

Greenpeace and local activists were arrested arbitrarily and on concocted charges with the clear motive of quashing the fight. The allocation of the coal block to Essar and Hindalco in the first place, much like the allocation of 203 others between 2004 and 2006, smacked of nepotism.

Later, it became the centre of a ‘go versus no-go area for mining’ fracas between conflicting priorities of the Indian government. During the two years of political musical chairs that ensued around Mahan, an environment minister close to Essar Energy took the chair from his contrarian predecessors.

The last hurdle for clearing Mahan, a full compliance with the provisions of the Forest Rights Act, was dislodged by the government through fraud. Desperate officials forged signatures of villagers to show that Mahan supported mining, and the environment minister signed on the dotted line of the final forest clearance.

Through Greenpeace, the locals became acutely aware of the implications of their anti-coal protests against the broader canvas of India’s politics around coal. At the most pitched point in the movement, women from Mahan staged Chipko-like demonstrations in the forests, sitting ringed around trees that company officials had come to illegally cut down.

Leafing through the diary notes of Kripanath Yadav, a prominent local voice in the movement, I discovered that they persisted with these blockades for five months. Others like Jagnarayan Shah who experimented with a stint at Essar’s thermal plant and then quit to fight the company lampooned past and present leaders’ false promises for Singrauli.

A rivered and forested landscape rich in coal, Singrauli in Madhya Pradesh formed the centrepiece of India’s idea of development. In the 1950s, the era of big dams, India’s first prime minister promised to transform the region to Switzerland. What he might have really meant was that Singrauli will bear the brunt of carrying out this dream.

The building of the Rihand Reservoir displaced a first wave of locals, mostly Adivasi and peasants. The elderly Bechenlal Shah, of Amelia village in Mahan recounted that his family was one of the ‘dam oustees’.

The family was forced to move again in the 1980s in the era of nationally owned thermal power plants. They finally settled on their present lands fringing the Mahan forests, only to realise the risk of displacement from the setting up of private mega thermal plants from 2006.

Madhya Pradesh’s long serving Chief Minister, Shivraj Chauhan promised to transform Singrauli to Singapore as he carved it out as a separate district in 2008 to facilitate private coalmining. Even though many of these super critical private-public thermal power projects have not truly taken off as governments and corporations intended, land acquisition, and consequently displacements have occurred.

Singrauli produces 10 per cent the country’s coal fired electricity, supplying to 16 states. In return it has earned seventh spot in the list of India’s most polluted industrial zones; the air hangs thick with mercury, fly ash and particulate matter. And, as is the pattern across most coal rich areas in the global south, 50 per cent of its own denizens live below the poverty line. Goes without saying that a comparable proportion live without electricity, the very resource it generates.

Together, Greenpeace and the Mahan movement stopped the first coalmine in the last stretch of virginal Sal forests in an otherwise ravaged Singrauli. Opening up Mahan would have unlocked the floodgates for others in the only remaining forest-tracks. Owing to the fracas that ensued from the unjust government crackdown on Greenpeace, civil society earnestly questioned the cost of coal in India and what genuinely is in the public interest.

Even if the Mahan victory ultimately proves to be a mere pause to breakneck development that threatens the fragile ecology and tramples on human rights, it will most likely remain with the locals as justice that was a long time coming.

The continuing harassment of Greenpeace on grounds of its ‘foreign’ status, and its subsequent silencing, were costs the government extracted for this justice. But, as Sudeep Chakravarty, author of ‘Clear, Hold, Build: Hard Lessons of Business and Human Rights in India’ puts it, inadvertently, the state has ensured that “this country’s abundant human rights can of worms remains open and spot-lit”.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.