DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

The destruction wrought by climate change is not a case of if, but when. Indeed it’s already happening. Dr Richard Hil has a plan for the future.

You’ll no doubt have noticed the sudden stampede of interest in all thing’s climate change? Some sections of the media just can’t get enough of it, especially the Fairfax Press. Even the Murdoch mob have taken note, more in an effort to sow further seeds of doubt than to affirm the bleeding obvious.

Whether you ‘believe’ in climate change or not – it’s often couched as a matter of faith – no-one, not even the most obdurate denialist, could help but acknowledge what occurred in January 2019. It was the hottest on record.

Tasmania, Victoria, Queensland and parts of NSW and Western Australia burned. Hundreds of thousands of hectares of bush, old forest and umpteen houses were reduced to ashes, and millions of animals were burnt alive. Townsville was overcome by biblical floods, and the drought in various parts of the country continued unabated. And then there were the dead fish in the Murray Darling Basin, another ghoulish occurrence of epic proportions.

The new zeitgeist

People seem shocked and bewildered by all this, as if introduced unexpectedly to a new form of inconvenient truth. Insurance companies have certainly got the message, hiking up premiums, while the Reserve Bank is telling businesses to wake up the what’s happening. As in many other countries, the military is reviewing its operations in light of more natural disasters and potential civil unrest.

The tectonic plates of Australia’s politics have shifted too. Opinion polls before the January boil-over were already sending clear signs of growing public disquiet over more frequent extreme weather events. People are beginning to take serious notice. There’s more talk of “the changing climate” and what and who might be responsible for it.

This unease is driven by the unknown and an accompanying sense of trepidation about what might unfold in the future. For some, the ‘dark knowledge’ of impending catastrophe has cut away at the illusion of certainty. Many are troubled in ways they haven’t been before.

In seeking to make sense of this, more and more of us are becoming alert to what is being said within our own circles, by the media, by scientists, and by the political and economic elites. Yet clarity is sparse and confusion abounds.

Back in early 2017, there was a lot of tut-tutting when then-Treasurer, now Prime Minister Scott Morrison held aloft a lump of coal in the federal parliament. Well, hasn’t that come back to haunt him? But the times are a-changing.

Coalition ‘sceptics’ increasingly draw the ire of a worried electorate for their reticence on the climate question. Coal-loving hardliners have been looking over their shoulders as determined opponents circle around them. GetUp! and various activist organisations have fixed their attention on unseating former PM Tony Abbott from his Warringah stronghold. (Interestingly, Abbott has recently decided, after no doubt perusing the latest IPCC report – or not – that he now supports the Paris emission targets).

Post-Wentworth

But it was the Wentworth by-election in October last year that really set the cat among the pigeons on the climate question. Voters rebuked the government at the ballot box for its cynicism on this issue. Cognitive dissonance seemed to lift from the collective conscience, as if the electorate had suddenly succumbed to a new whiplash reality.

Since Wentworth, the polls have been showing an inexorable rise in public concern over what some, like me, prefer to refer to as the climate emergency or climate chaos. A recent Fairfax poll in NSW indicated that voters are more likely to support parties and independents who are demonstrably serious about climate action. Faced with this, the recently re-elected NSW Liberal leader, Gladys Berejiklian, declared her party’s, belief that climate change is “real” (even though she seems very reluctant to talk to her government’s own climate advisory committee), and that her administration is doing everything in its power to address this wicked problem (while also supporting the construction of vast underground mines in the Hunter Valley, endorsing land clearance and CSG mining).

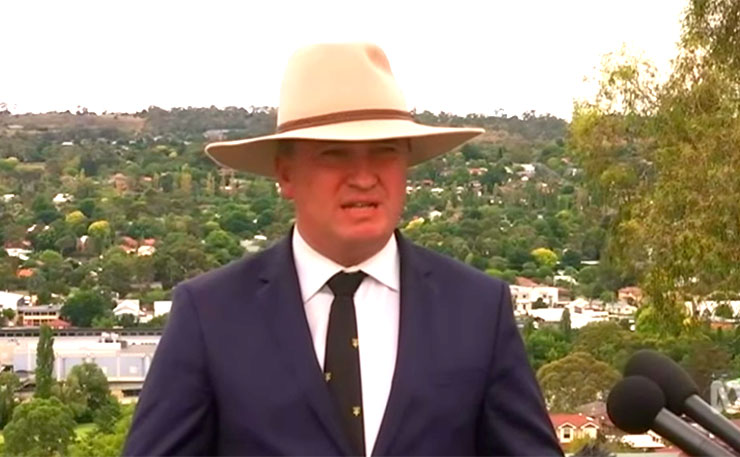

Further afield, former Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce, along with some of his errant National Party colleagues, most notably the Mackay maverick, George Christensen, called for the construction of a government-subsidised coal-fired power station in Queensland. This was too much for Joyce’s jittery colleagues facing an election wipe-out (which duly occurred in the recent state election, with votes leeching to the Shooter Fisher and Farmer Party). Joyce was roundly chastised for destabilising the party and told to shut up.

Given the new zeitgeist, Coalition members, federal and state, are now falling over themselves to announce their climate change credentials and their commitment to action. Quite what sort of action, they’re not exactly saying since there’s no coherent plan to deal with this problem. In fact, the Coalition government under ScoMo has sought to fudge the carbon emission figures by including Kyoto carbon credits in its calculations and has, until recently, insisted that lower energy costs are its priority.

As this depressing charade has played out, carbon emissions have risen drastically since 2011, and there are no signs that the current government will significantly cut fossil fuel production. Additionally, no-one is quite sure what an incoming Labor government will do on the matter of, say, coal extraction, with mixed signals coming from various quarters.

From bastardry to sense-making

The deceit and recklessness of some politicians and their corporate mates is the most egregious form of bastardry. Happy to ignore or ridicule the science, they are nonetheless running against the grain of public opinion. As Rebecca Hartley notes in the most recent Quarterly Essay, governments of both left and right appear to respond more to their donors’ policy preferences than to the will of the people.

This is not uncommon, especially in the US and Britain, but it is also happening here, thereby generating what many consider to be a deepening crisis of political legitimacy.

Recently, as thousands of Australia’s schoolkids joined an international climate action protest, we were reminded of the vital importance of mass civil action, especially on this most crucial of issues.

It’s not the only wicked problem that confronts us, of course. The threat of nuclear war lingers, racist ethno-nationalism has re-merged, inequality has deepened, and we are experiencing what David Suzuki has referred to as an “ecological holocaust”.

Some scientists are now talking openly of the possibility of planetary extinction, or something not far off. It’s hard to imagine how that could happen, but it’s a real prospect based on the current scientific predications, which can barely keep up with the scale and pace of change.

Writers like Clive Hamilton, Dhar Jamil and Catherine Ingram have reflected on the implications of the climate emergency, and how we might live in the future, assuming there is one. They’re not entirely clear – how can anyone be? – about precisely how the devastation will unfold, although the tell-tale signs are already here in terms of more frequent and prolonged extreme weather events.

Farmers, firefighters, park rangers, wine producers, horticulturalists and those who study the climate are telling us what many of us already know; we have entered an era of the Anthropocene in which much of what is occurring is already, and alarmingly, out of our control. This gloomy vista rubs against the hubris associated with the enlightenment’s cult of science which lauded the belief that the Earth, over which ‘man’ claimed dominion, was at our service.

It’s a belief that still resonates with many, offering a justification for continued planetary destruction. Some technocrats maintain that geo-engineering may yet save us from calamity, even though its financial cost and effectiveness are in serious question.

At some point, what may begin to open Overton’s window is the unpalatable – make that terrifying – prospect of finality, or at the very least, a drastic reconfiguration of life on Earth as we know it. For Ingram (in her brilliant essay, Facing Extinction) and Jamil (in his book, The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption), the task now is to seek to somehow rebuild social infrastructure, and create regenerative and life-supporting communities that can at least offer temporary respite.

Another goal is to celebrate the most fundamental things that have always made life worthwhile: love, connection, belonging, compassion and kindness.

Deep adaptation

The end of the world is nigh? I never thought I’d take that seriously – well; not the religious version. Sure, I was and remain worried about the nuclear threat, but there was a sense that the madness of Mutually Assured Destruction could stave off annihilation, Trump notwithstanding.

The climate emergency has its own unfolding logic. Granted, evoking the end, or a radically diminished form of life, isn’t exactly what you or I want to hear, but it may be the unpalpable truth we might have to face up to.

As I say, we don’t know what this sort of catastrophe looks like and, as journalist Phillip Frazer has reminded me, the end game will be chequered and variegated, impacting most severely on the poor and marginalised. A few of us may survive, but millions, perhaps billions won’t.

I can’t believe I’m writing this sort of stuff, and just a few years ago I would have sectioned myself for doing so. But it’s where my listening, thinking, reading and writing have taken me. I’ve had to rethink my political activism, my relationships, in fact, just about everything I do. I’ve even had to reconsider my deep anger towards those who have taken us to this point – it’s simply too exhausting.

None of this means that I’m going to retreat to some sort of survivalist bunker or to an inward-looking enclave, but I will balance my activism more assuredly with a commitment to the good life, as I see it. Come to think of it, there’s really no separation between the two. One thing I’m not going to do is pretend that everything will be OK.

Which brings me, finally, to English academic, Professor Jem Bendell and his remarkable essay, Deep Adaptation: A Map for Navigating Climate Tragedy. Much in this intelligent analysis echoes what Ingram, Jamil and many others are now saying. Bendell’s proposition is that the impact of extreme weather events brought on by the triple whammy of global warming, and destruction to biodiversity and ecological systems, will result, inter alia, in the collapse of food production and distribution networks and a corresponding implosion of the world’s financial systems, plunging the entire planet into chaos and confusion.

Professor Bendell talks in his article and elsewhere of the possibility of “extinction” but dwells more on the manifestations of collapse and what this might mean for the planet, its species, ecologies and civic life as we know it.

Bendell’s work is exploratory, sometimes tentative and awkward, but always insistent on the need to conduct a meaningful dialogue about the effects of climatic and other changes that hitherto many of us thought impossible.

This necessarily raises some very challenging questions and it’s no surprise that many of Bendell’s detractors consider his work too confronting and perhaps unhelpful in enabling us to seek to avert the worst. While he largely dismisses any last-minute rescue mission via geo-engineering, Bendell does hedge his bets somewhat when it comes to the climate emergency by suggesting things we can do to find solace in the company of others, and to eke out a life-saving food supply. This suggests that he believes some of us may survive, and that some resilient communities may emerge.

What’s not so clear in Bendell’s analysis, however, is who and where these communities might be, or how they might be able to survive the unfolding tragedy. That said, Bendell’s ideas do not amount to shotgun survivalism, or a retreat into the world of despair. Rather, he is raising questions that require serious contemplation. He is inviting us to reflect on the emotional and spiritual states that will be greatly challenged in a crisis-ridden scenario.

Bendell is no sociologist of course. There’s little or no reference to class and power in his work, and he doesn’t seem to have a handle on how the collapse will manifest differently in various locations. Yet he does acknowledge the dark spaces that will arise in a situation of which we know little at this juncture: the despair, panic and rabid self-protectionism. But there’s another, more life-affirming side to all this.

Ultimately, Bendell is calling for us to acknowledge and respond, rather than react, to what is unfolding, and not necessarily to latch onto blind faith, disengaged hope or another activist crowd. At the same time, he urges us all to never give up on mitigation and adaptation, and never abandon our activism, whichever form that takes.

The “deep engagement” of which Bendell speaks is a commitment to engaging with our emotional and spiritual sides, and to seek to build loving, kind, collaborative regenerative communities – something we should have prioritised long ago. Bendell’s right, we need to radically rethink our stories: abandoning some and creating and affirming others if we are to cope with what’s at hand.

DON’T MISS ANYTHING! ONE CLICK TO GET NEW MATILDA DELIVERED DIRECT TO YOUR INBOX, FREE!

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.