A new Australian film challenges the notion of our supremacy in places like Afghanistan. Therese Taylor reviews Jirga.

Australia is beginning to feel the cost of its military involvement in Afghanistan. This year, the media has published a series of disturbing stories about war crimes committed by Australian troops. An enquiry is being conducted by Justice Brereton, of the NSW Supreme Court, and this is predictably raising controversy.

The deployment of troops in 2001 has extended to the present day, and there is no obvious end in sight. What is in sight is guilt, recriminations, insoluble loss and the enigma of Afghani culture.

The film Jirga, directed and written by Benjamin Gilmour, has appeared at this fateful moment. The story is of a former Australian soldier, Mike Wheeler, who returns to attempt a reconciliation with an Afghan household. He killed the father of the family in a raid, and now wants to put things right.

Jirga can be seen as political text, showing us the long-term cost of military involvement. It is also a study in communication between cultures. In an unusual move, much of the dialogue is not subtitled, so that the audience accompanies the lead character in moving through a series of encounters where he does not understand what is being said to him.

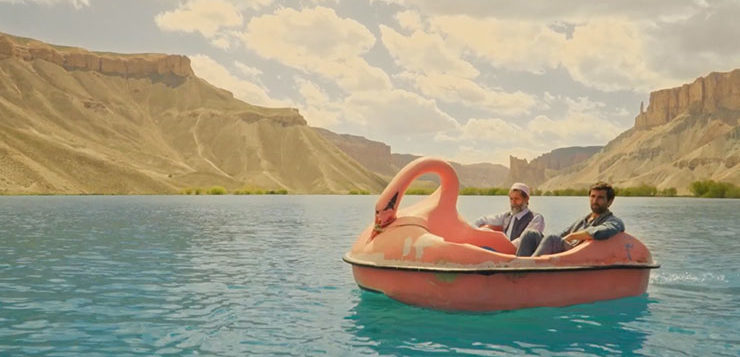

Benjamin Gilmour is a creative and daring film-maker, who took the risk of filming in Afghanistan. The film cuts directly to the stark landscape and vivid dilemmas of an ongoing war. The cinematography is stunning. One moves between views of transcendent beauty and gloomy struggles. Throughout various scenes, one can feel the reverberations of the real conflict going on nearby.

In interviews, Benjamin Gilmour has explained his aim: “Hollywood has always sold us the lie that we can shoot our way to a happy ending,” Gilmour says. “It’s very rare there’s a happy ending at the end of a war, certainly in the last two decades.”

The film is filled with symbolism, and one can trace spiritual messages through scenes such as Mike Wheeler diving into the endless waters of the Band-e Amirlake. He returns to the surface subtly refined into a new beginning, with a sense of purpose.

Like most Australians, he knows that the environment is as great a danger as any weapon, and collapses from heat exhaustion in the hills. His capture by the Taliban, where two Afghan men drag him along the ground into a cave, is a nadir where he has his turn as the helpless one facing armed men. Always, he is trying to explain himself, and he never quite succeeds. One of the superb qualities of Gilmour’s script is that it allows for mutual incomprehension alongside understanding.

The actor, Sam Smith, has the ability to play this role with a light touch and aura of naturalness.

The final scene, after the Jirga from which the film takes its name, is of reconciliation. A lamb is sacrificed, according to the Abrahamic ritual, and in the space between death and life, the villagers join up with their strange visitor. In its subtle way, with impressive performances by the Afghan actors, the film conveys the arguments of the Jirga, which resolve into unity in the choice between retribution or forgiveness.

When watching this, I recalled Wilfred Owen’s anti-war poem from World War One. In a biting satire, Owen describes the binding of Isaac and concludes:

“Behold, A ram, caught in a thicket by its horns;

Offer the Ram of Pride instead of him.

But the old man would not so, but slew his son,

And half the seed of Europe, one by one.”

That, after all, is the alternative. In our time, the lessons of previous wars have become distant. There is an illusion that conflicts will always be safely fought elsewhere, and that the cost is bearable.

Jirga is an unusual and compelling film. It has an important message, and it is almost the only chance most of us get to see the Taliban represented realistically in their own environment. It is also a work of art, and Benjamin Gilmour can be proud of this great achievement.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.