Every year a report card on the government’s performance in lifting Indigenous Australians out of poverty documents more and more failure, and a widening gap. Professor Jon Altman explains why.

I have been visiting Aboriginal communities in remote Australia for over 40 years. In the last decade, particularly since the NT Intervention, I have observed both the destruction of lifeways and the entrenchment of deepening poverty.

In many places people are making valiant and productive efforts to make a living, but against mounting odds. And in some sectors like in caring for country, caring for people and cultural industries there are glimpses of success and embryonic signs of what might be.

There is also a growing body of evidence, much based on official statistics gathered by the Australian Bureau of Statistics and other agencies and analysed by independent researchers, including myself, that indicate that my grounded pessimistic observations reflect a change that is widespread across the massive geographic regions, remote and very remote Australia. These regions encompass 86% of the continent, but have an estimated Indigenous population of just 140,000.

In this article, I want to highlight the plight of Indigenous people in remote Australia, juxtaposing this with the far more benign perspective on acknowledged failure provided in the Closing the Gap Prime Minister’s Report 2018, recently tabled in the Australian Parliament.

This is the 10th report in a row, five delivered by Labor Prime Ministers (2009–2013) and five delivered by Coalition Prime Ministers (2013–2018), that shows that at the national level the Australian government, in partnership with States and Territories, has failed to reduce disparities in socioeconomic outcomes between Indigenous and other Australians.

I then want to look more closely at the unfolding tragedy of what is happening in remote Australia focusing on the last decade, look to provide some explanation of why at a time when governments frame their narrative on ‘closing the gap’ in some geographic regions disparities are clearly growing.

I want to further unsettle and challenge the dominant narrative by asking whether in the past decade government intervention, ideologically driven by the notion of delivering socio-economic equality, has actually made things worse for the subjects of its project of improvement, even according to the government’s own ways of measuring.

Rather than concluding with a list of proposed solutions to what is a complex politically charged issue, I want to challenge politicians, officials and others to refresh their thinking and break out of a path dependency that is proving financially wasteful and truly destructive for the very people that statistics present in abstract and generalised form—perhaps seeking to conceal their suffering from public gaze.

More sizzle, less sausage

A feature of the Closing the Gap reports is how each year they have become glossier and thicker. This year represented a ‘day of reckoning’ when four of the original five disparity targets were to be met.

The annual reports originally conceived to hold Australian governments accountable for their performance have been increasingly deployed to narrate stories of dramatic success, with the message that these are replicable, and to outline all that the Australian government is doing. In other words, a form of propaganda.

For the first time, right up front, there is a summary of performance not just at the national level, but also at State and Territory levels. While the National Indigenous Reform Agreement of November 2008 that formalised the Closing the Gap targets was a joined-up Council of Australian Governments initiative, one senses that the Australian government is now keen to share the blame for failure with other governments.

This is though it was Kevin Rudd’s national government that unilaterally developed the targets announced in February 2008 as an adjunct to the National Apology. An elixir of billions of dollars in National Partnership Agreements was used to entice State and Territory collaboration. But targets were set at the national not sub-national level.

Let’s be clear that these disparity targets are modest: to halve the gap in child mortality by 2018; to halve the gap in reading and numeracy by 2018; to halve the gap in Year 12 attainment by 2020; and to halve the gap in employment outcomes by 2018.

The other three targets are to close the gap in life expectancy by 2031; a revised target to have 95% of Indigenous four-year olds in early childhood education by 2025; and an ambitious new target devised by Tony Abbott when ‘Prime Minister for Indigenous affairs’ to close the gap in school attendance between 2014 and 2018.

In this latest report the Australian government has made a valiant attempt to manipulate statistics to show that three targets are on track.

In fact, only one – year 12 attainment – might be on track. I say might because recent research published by the Grattan Institute shows widening gaps, referred to as a gulf, in learning outcomes especially in remote and very remote areas.

The information on child mortality provided refers to trends from 1998 with most progress already achieved by 2008. And the early childhood target is not a gap but information of enrolment in early childhood, ‘reset’ in 2014 to extend its timeframe for another decade after failure to meet the original target by 2013.

It is a sad indictment of a rich settler society like Australia that what are quite modest goals nationally have not been achieved.

But it also needs to be said that even in 2008 there were commentators and academics, myself included, that predicted this outcome.

Such prediction was based in part on earlier experience with the Aboriginal Employment Development Policy in 1987 that had set out to statistically eliminate disparities in employment, income and education by 2000. And in part on historical statistical trends going back to 1971 when Indigenous people were first allowed to self-identify in the Australian census.

Two other factors, beyond the statistical, stand out as explaining the 10-year policy failure.

What went wrong?

The first is conceptual or ideological: any notion of elimination of disparity must be based on a logic of sameness. To put it crudely, if Indigenous people are to have the same standard of living as other Australians they will have to live in similar locations, informed by similar norms and values, engage with the mainstream market capitalist economy and society in the same way. This approach resonates with the assimilation policy as defined in 1961.

Back in August 2007 Prime Minister John Howard looked to justify the NT Intervention while visiting the remote township of Hermannsburg, he put it to Indigenous Australians in this brutal way: ‘become part of mainstream society or face a bleak future’. This prediction too has proven correct as Indigenous people have resisted such incorporation.

This is especially so for those Indigenous Australians who do not want a future as part of the mainstream but prefer to live differently. As then Chairman of the NLC stated, also in August 2007 to members of a Senate Committee examining Intervention laws, ‘Does every Aboriginal person necessarily want to be like you guys?’

The second is the fundamental difference in the geographic distribution of the Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations: while 20% of Indigenous peoples live remotely only 1.5% of the non-Indigenous population do so.

What is more, most of this remote Indigenous population resides in about 1,000 small communities spread across Indigenous-owned lands held under land rights and native title laws. Such titles have largely been legally bequeathed because their owners have demonstrated forms of ‘continuity of rights and interests under traditional laws acknowledged and traditional customs observed’ and ongoing connection to their ancestral lands.

As more and more of remote Australia has come under various forms of Indigenous title varying from inalienable freehold title to exclusive possession to non-exclusive possession, land owners have looked to occupy their lands and utilise their resources for livelihood.

These are circumstances that enable the maintenance of diversity and difference, the high culture and ‘a history of 65,000 years’ that the Closing the Gap report celebrates. Landowners with aspirations to live on their homelands should not be condemned to live in dire poverty by governments.

There is no engagement with this reality either in the framing of Indigenous policy or in the Closing the Gap annual reports. And there is no attempt to document the extent of the socioeconomic disparities for remote Indigenous Australia — even though an element of current government policy has distinct Remote Australia Strategies.

Let me turn now to expose just a few aspects of what has been papered over by the statistical focus on failed national performance and then explore briefly the role of government policies in intentionally and unintentionally impoverishing remote Indigenous Australia.

How we got there

Recent research by Francis Markham and Nicolas Biddle from the Australian National University shows that for the first time, more than half of the Indigenous population in very remote Australia is in income poverty. In some regions like Nhulunbuy and Jabiru Indigenous poverty rates are as high as 69.3% and 67.7%.

Indigenous income in very remote Australia averages just 44% of median non-Indigenous income. And Indigenous poverty rates have increased in very remote Australia between 2006 and 2016 by 7.6%.

While income poverty is not one of the Closing the Gap targets, employment is, with data from the last three censuses showing that the Indigenous employment rate has declined in absolute terms in remote Australia.

As the non-Indigenous employment rate has hovered about 80% between 2006 and 2016, the Indigenous rate has declined from nearly 50% to just over 30%. In remote Indigenous Australia the disparity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous employment is growing; and the absolute rate of Indigenous employment has declined to the extent that only 3 in 10 Indigenous adults are in paid work.

This trend in paid labour underutilisation combined with inadequate social security payments has caused the alarming escalation of Indigenous poverty in remote Australia. Coupled with the high price of basic foods in most remote communities this explains the deep poverty that I observe when I visit.

While I focus here on poverty and employment rates, the disparities in all the Closing the Gap targets are greater in remote Australia than elsewhere.

This extraordinary socioeconomic decline that has seen the poorest Australians become even poorer has multiple explanations that are interlinked in complex ways.

Some are structural and outside Indigenous policy, although they have disproportionately impacted on remote living Indigenous people.

For example, changes in the mainstream social security system have generated multiple jeopardies that excessively impact on remote living Indigenous people.

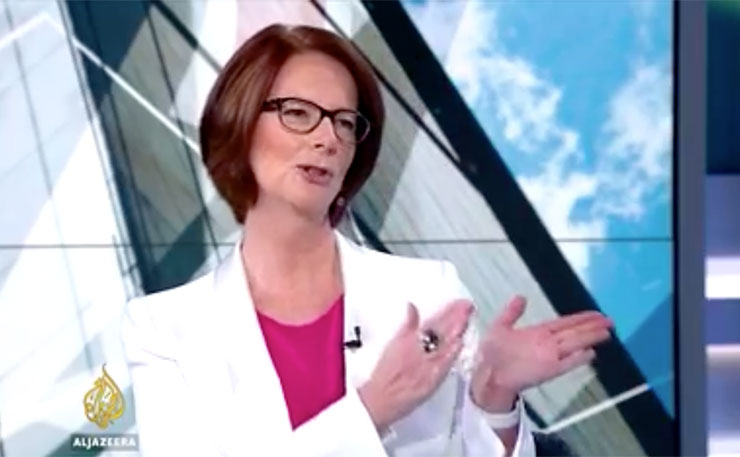

These include: the reduction in parenting payment introduced by the Gillard government; the growing gap that has developed between the more generous Aged pension where Indigenous people are under-represented (owing to lower life expectancy) and Newstart allowances where Indigenous people are over-represented; and the escalating difficulty that Indigenous people living remotely experience in accessing the Disability Support Pension as documented by the Commonwealth Ombudsman in detail in 2016.

These are all factors that have impoverished Indigenous people that the Australian government has chosen to ignore.

But of greater significance than such ‘mainstream’ explanations is the extraordinary shift in Indigenous policy in remote Australia in the aftermath of the NT Intervention.

Neither the Intervention nor this policy shift to punitive neoliberalism rate a mention in the Closing the Gap report.

The dominant and bipartisan political view that has driven this new approach is that paternalistic measures need to be deployed to alter the norms and values and ways of behaving of remote living Indigenous people to align with those of neoliberal individualistic subjects.

I do not want to rail here against the illiberal, paternalistic, racist and as we now see unproductive and wasteful nature of these measures in any detail. I have done so on numerous other occasions.

What I do want to do is comment on how the draconian nature of these measures have ramped up over time by focusing on two instruments, income management and remote work-for-the-dole, to demonstrate how destructive and ‘gap widening’ this approach has been.

Widening the gap

When elected in late 2007, the Rudd government could have ended the folly of the ‘national emergency’ but it chose not to, despite no evidence of any improvements and two important independent reviews, first of the Intervention umbrella; and then on income management via the BasicsCard that cost the Australian taxpayer over $1 billion to implement.

Indeed, by acquiescing to this ‘interventionist’ approach first the Rudd and then Gillard administrations gave it moral authority; and then having invested heavily in its escalating implementation over five years, renamed it Stronger Futures for the Northern Territory and locked it in for another decade.

When elected in 2013 the Abbott government appointed a mining magnate Andrew Forrest, to review Indigenous Jobs and Training. A government member Alan Tudge, a fan of behavioural economics and with work experience at Noel Pearson’s Cape York Institute, and academic and public intellectual Marcia Langton joined the review team.

Implemented recommendations from this review have seen the further escalation of draconian measures with the piloting of the highly contested Cashless Debit Card and the introduction of the Community Development Programme (CDP) that requires people to work daily for up to 25 hours per week for their Newstart payments.

Two papers published by the ARC Centre of Excellence for Children and Families over the Life Course in December 2017 provide damning evidence on just how destructive income management might be.

The first examines the link between income management and child health. It provides very strong statistical evidence that income management did not improve child health outcomes but actually damaged newborn health — causing a reduction in average birth weights.

The second examines the effect of quarantining welfare on school attendance. It found that the introduction of income management caused school attendance to fall in the short run. Furthermore, this paper argues that the way that income management was implemented may have resulted in income insecurity, barriers to day-to-day economic activity, and a loss of empowerment which may have led to increased family stress and had adverse consequences for parenting.

In terms of Closing the Gap targets in remote Australia these studies illustrate negative impacts from intervention; neither is mentioned in the Closing the Gap report. And if quarantining 50% of income has negative impacts, one must ask how much more negative might impacts be from the cashless debit card that quarantines 80% of income?

Numerous studies have highlighted the relative benefits of the community managed Community Development Employment Projects (CDEP) scheme over the very inferior schemes that followed — Jenny Macklin’s Remote Jobs and Communities Program (RJCP) 2013–2015 and then Nigel Scullion’s CDP.

The Closing the Gap has a lot to say about the achievements of CDP but forgets to mention the Australian government’s punitive willingness to apply 350,000 impoverishing financial penalties on 34,000 participants, most of whom (84%) are Indigenous.

Nor does it mention that in the 60 CDP administrative regions the Indigenous employment rate is less than 30%, with many regions having a far lower rate (as low as 13% in CDP Region 23 ‘Alice Springs District’).

Nor does it mention how with CDEP (that operated 1977–2015) there was more employment, more income, more community enterprise and more empowerment of Indigenous people to utilise their vast lands and natural resources assets for livelihood improvement.

The government knows this and so is now looking to reform CDP while at the same time allowing it to continue to force people to work in modern slavery-like conditions for 25 hours per week for the dole, and to be more and more impoverished with relentless penalties.

The complacent Turnbull government’s response to all this is to launch Closing the Gap Refresh. An unnamed official in Canberra has decided that a strengths-based approach is now needed, and the new framing buzz word is ‘prosperity’: ‘moving beyond wellbeing to flourishing and thriving’.

I wonder what people in the bush struggling for a feed make of this discursive shift?

I am reminded of American political scientist Murray Edelman who wrote about ‘words that succeed and policies that fail’. With Closing the Gap, both the policies and the words have failed so rather than refreshing the overall approach the government is scrambling for new words.

There is a need to refresh the approach to clearly distinguish the circumstances of remote and non-remote Australia. We can learn from the Hawke government’s approach informed by a comprehensive review chaired by the late Mick Miller in 1985.

Alongside an aspirational but unachievable commitment to statistical equality there was clear commitment to accommodate difference with a community-based employment and enterprise strategy: ‘The purpose of the strategy is to support the aspirations of Aboriginal communities to undertake development in a way that is controlled and is determined by those communities’.

The ideological commitment to sameness for Indigenous people who must legally prove difference through land rights and native title claim procedures lacks logic and must be reversed. And the expensive, racist, damaging and demeaning punitive measures currently deployed by the hegemonic and unsympathetic state must stop.

A way forward

I am not a policy nihilist or anarchist: there are compelling reasons why the Australian government should be required to meet the needs of remote living Indigenous people as citizens. There are equally urgent social justice reasons why as a conquered and subjected people Indigenous people should be afforded special compensatory rights.

A prerequisite for refreshing the policy thinking must be an acknowledgement of the crushing failure of the last decade and the deepened impoverishment in remote Indigenous Australia.

An openness to a range of possible alternate approaches is needed that recognises development as a process that is not only integration into market capitalism that can be totally absent in remote Australia.

A practical and empirically-informed framework is needed based on negotiated principles.

Some that come to my mind to stimulate overdue ‘refreshed’ debate include: local control; responsive to Indigenous aspirations and circumstances in all their diversity; adherence to international non-discriminatory human rights standards; a consideration of all production possibilities, inclusive of the customary and cognisant of the land titling explosion; new or enhanced existing institutions for empowerment; recognition of the intercultural mix of western and customary norms and values that remote Indigenous people live by; support for cross-cultural forms of hybrid governance arrangements; and creative engagement with global development thinking especially in those settler societies that have managed decolonisation and governance for sustainable development far better than Australia.

* A version of this article was first published in Land Rights News.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.