The Turnbull Government has responded swiftly and justly to the final report into the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses To Child Sexual Abuse. And then there’s the response to the Bringing Them Home report, and the stolen wages scandal across two decades, and successive governments. The double standard is there in black and white, for anyone who cares to look. Chris Graham reports.

One of the really useful things about the #changethedate campaign is that it serves as an effective litmus test for our maturity as a nation. For how we see ourselves, for our capacity to honestly face our past, and our ability to empathise with a people who were brutalized in our names, for our benefit.

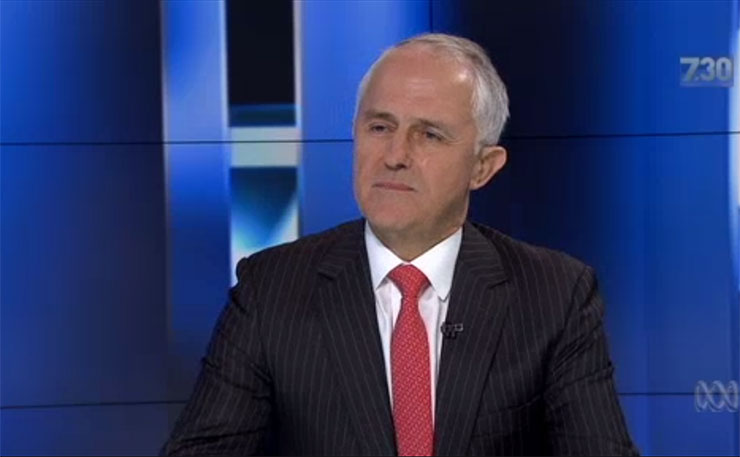

That we even have to debate celebrating a day which marks the dispossession and slaughter of another people speaks volumes about our national maturity. That we have a Prime Minister who then sees the political capital in assuring his base nothing will change while he’s in charge; and that we have an Opposition leader who falls over himself to get in step quickly, adds to that sad picture.

But you don’t have to look a whole two weeks back for the results of the national litmus test. You only have to go back to Thursday, when news broke that Malcolm Turnbull’s Government has upped the pressure on the states and territories to get behind a Commonwealth scheme that will compensate child victims who were sexually assaulted while in government care.

It follows the handing down in December last year of the final report from the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. There are 189 recommendations.

Turnbull’s scheme was actually announced in November 2016, more than a year before the final report was delivered. Then, he promised a “massive compensation scheme” for victims. This week he announced there would also be a parliamentary apology before the end of the year: “Now that those stories have been told, now that they are on the record, we must do everything within our power to honour them.

“As a nation, we must mark this occasion in a form that reflects the wishes of survivors and affords them the dignity to which they were entitled as children, but which was denied to them by the very people who were tasked with their care.”

No-one batted an eyelid. And why would they? The notion that children who are sodomised, beaten and tortured at the hands of the state and their (largely religious) agents should be compensated for a lifetime of deep pain and suffering is hardly a controversial one.

Bill Shorten was quick out of the gates as well, joining Turnbull in heaping pressure on those responsible.

“As of today, not a single dollar has come from any of the states or the institutions whose names and deeds fill the pages of this report,” Mr Shorten said. “I say to the institutions, and indeed the states: the time for lawyers is over, the time for justice is here.”

The fact is, the Commonwealth doesn’t have to provide a national apology, nor does it have to create a Commonwealth scheme. Liability for the atrocities committed against children in institutional care lies largely with the states and territory governments, and their agents.

But Turnbull is doing so – and Shorten is backing him – because any other response is unthinkable. It would be contrary to our national values to turn our backs on such visceral pain. It’s leadership in response to a dark chapter in our recent past. And speaking of dark chapters….

Bringing Them Home

Contrast the Turnbull and Shorten responses to the Royal Commission with the major parties’ responses – which now span 21 years – to the Bringing Them Home report, the end product of the National Inquiry into the Separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from Their Families.

The Inquiry was established in 1995 by Paul Keating’s Attorney-General, Michael Lavarch and documented the theft and removal of Aboriginal children over decades by government institutions and, again, their agents. Bringing Them Home also shed light on their treatment while in care. The words ‘rape’, ‘abuse’ and ‘assault’ appear dozens of times throughout the report.

“Children in every placement were vulnerable to sexual abuse and exploitation…. Almost one in ten boys and just over one in ten girls allege they were sexually abused in a children’s institution,” Bringing Them Home noted.

“Almost 1 in every five (19%) Inquiry witnesses who spent time in an institution reported having been physically assaulted there.”

One of the report’s recommendations references how the states and the Commonwealth should specifically deal with the victims of torture.

Unfortunately for the mob, Lavarch and Keating were not in power when Bringing Them Home was published, two years after the inquiry commenced. John Howard was.

524 pages long with 54 recommendations, the report was begrudgingly tabled in Federal Parliament on May 26, 1997. The Howard government made no real effort to mask its disdain. A day later, Howard travelled to Melbourne as a guest of the National Reconciliation Convention. That’s the speech where Howard banged his hands on the lectern and yelled at the gathering, only to have audience members stand and turn their backs on him.

There would be no compensation. There would be no apology. Instead, a year later, Howard delivered his ‘statement of sincere and deep regret’. It was time to move on from the “blemishes” of our past, he said.

Nearly a decade later, Howard was voted out of office. Enter Kevin Rudd, who won promising to apologise to members of the Stolen Generations and, through Labor’s 2007 National Platform, provide a “comprehensive response” to the Bringing Them Home report (he also promised a treaty, constitutional recognition, and to move Australia Day to a more inclusive date… other stories for other days).

Rudd delivered the National Apology on the second sitting day of the 42nd Parliament in 2008, but he withheld reparations, telling the nation: “The intention is to build this bridge of respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia. (Then) we can get on with the business of closing the gap in terms of life expectancy, education levels and health levels between Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.

“We will not be establishing any compensation funds.”

It was a pitch to a cynical nation, and it worked. Prior to the apology some polling suggested almost two thirds of the population were opposed. After the apology, with no compensation, polling suggested around two thirds of the population were now in support.

Job done, move on. Except that Stolen Generations members and Aboriginal people more broadly could not move on, because they never stopped demanding they be afforded the justice everyone else gets.

A month after the apology, Deputy Leader of the Democrats, Senator Andrew Bartlett introduced a Private Members Bill to parliament. Called the Stolen Generations Compensation Bill, as the name inferred it pushed for individual reparations, just as the Bringing The Home report had recommended, and just as Labor had inferred it would deliver.

The Bill was blocked by the Rudd Government and the Liberal/National Opposition. A few months later, Greens’ Senator Rachel Siewert reworked it and reintroduced it as the Stolen Generations Reparations Tribunal Bill 2008.

Still fresh from basking in the warm glow of widespread international praise for the National Apology, the Rudd Government’s response to the Bartlett-Siewert Bill was as swift as it was brief.

After the parliamentary committee with oversight of the Bill recommended against it’s passage, the Rudd government agreed, adding: “The Government has indicated on a number of occasions that it will not be providing compensation to members of the Stolen Generations. For this reason the Government has no specific comments to make on the aspects of the Bill relating to compensation for the Stolen Generations.”

Rudd had little to say publicly too, mostly ignoring and deflecting media questions until journalists lost interest.

But out of office – like so many leaders before him – Kevin Rudd rediscovered his courage and his moral compass. In 2015, with no hope of ever returning to power, Rudd argued that individual compensation should be paid to members of the Stolen Generations. Such is the thickness of his skin – and the superficiality of his intent – that Rudd has continued to dine out on his role in the National Apology, despite this betrayal.

As an interesting aside, Senator Rachel Siewert had another crack with a re-revised Bill in 2010. It met the same fate.

Labor’s Julia Gillard was the Prime Minister at the time.

Stolen Wages

The hypocrisy in government responses to the Stolen Generations is stark. But it’s even more outrageous when you consider the Bringing The Home report documented more than just the theft and brutalisation of Aboriginal children. It also probed Australia’s modern spin on the age-old practice of slavery.

As Aboriginal children were snatched from their homes, many were farmed out to white institutions and individual families as labourers and domestics. They were either paid a pittance for their work, or nothing at all. The iconic 1983 film Lousy Little Sixpence is about the stolen wages scandal.

The money that should have been paid to black workers was held in trust by state governments, and by the Commonwealth in the case of the Northern Territory. In innumerable cases – literally innumerable, because governments across the nation now claim to have lost most of the financial records – the money was either stolen by government employees, or re-directed by bureaucracies and politicians to provide basic infrastructure, often for the exclusive use of non-Aboriginal citizens.

The Queensland lost and stolen wages, for example, helped fund hospitals and hostels, which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were then barred from accessing. Roads were built on which Indigenous people couldn’t drive, either because they were banished to faraway missions and islands, or they had no financial means to buy a car and their movements were restricted by virtue of the permit system of the day.

In 2002, the Beattie Labor Government offered Aboriginal workers – many of whom had lost a lifetime of wages – $2,000 in compensation. But to get it, they had to sign a waiver forfeiting their right to future legal action.

That scheme has taken on various iterations ever since – successive Queensland governments have tried in vain to clean up the mess and avoid the inevitable litigation, to no avail. It is currently the subject of a pending class action by victims and their families. The nation’s foremost expert on the issue, Dr Ros Kidd, estimates that up to $500 million (in today’s terms) was stolen. The Queensland Government is currently offering to return $21 million of it. Peter Beattie’s original scheme was just over $50 million.

The theft and subsequent betrayal of slave workers wasn’t just restricted to Queensland, of course. In NSW in 1997, then Labor Minister for Community Services, Faye Lo Po’ wrote a cabinet submission admitting the theft of $69 million in Aboriginal wages by previous state governments between 1900 and 1969.

Lo Po’ recommended the establishment of a repayment scheme, with individual reparations. Then Labor Premier, Bob Carr, had the minute suppressed.

It never saw the light of day until it was leaked (to this writer) in 2004. Carr had only recently launched Long Time Coming Home, a book charting the life of Stolen Generations icon Marjorie Woodrow. He spoke about the importance of stories like Marjorie’s being told.

A new draft cabinet minute was written. It now estimated the theft at up to $80 million. That minute was also leaked amid attempts by the NSW Government to reduce its liability. In the end, a restrictive reparations repayment scheme was established. Questions tabled in parliament in 2011 reveal that, ultimately, just over $6 million was returned. A NSW Parliamentary Inquiry in 2016 recommended the re-establishment of the Aboriginal Trust Fund Scheme. Nothing has happened since.

Re-enter Democrats Senator Andrew Bartlett. In 2006, he also led a federal parliamentary inquiry into the lost and stolen wages and savings scandal. That report – Unfinished Business: Indigenous Stolen Wages – was tabled on December 7, 2006. It received bi-partisan support from the Howard government and the Rudd-Labor opposition.

Says Bartlett: “In a general sense it did (receive bi-partisan support), but part of why that was was because the Commonwealth didn’t need to do very much.”

Like the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, liability for the lost and stolen wages and savings largely rests with the states, although the Commonwealth is responsible for monies stolen in the Northern Territory, which it administered until the late 1970s.

Regardless, nothing has ever eventuated from that report either, despite its bi-partisan support. There has been no Commonwealth push for a coordinated scheme. No national leadership. No pressure on the states and territories to deal with the issue comprehensively and fairly. The Howard, Rudd, Gillard, Rudd, Abbott and Turnbull Governments have done precisely nothing to advance the cause, or return the stolen monies.

“It would be like the Royal Commission (into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse) handing down their report, and the government responding, ‘Good luck in court folks’,” says Bartlett.

“That would never happen, but it is what has happened with the Stolen Generations and the Stolen Wages cases.

“And it’s ongoing. They are re-traumatising people by not giving them fair compensation, and through the added trauma of having to fight the system through the courts. It just compounds the harm.”

The ups and downs

There have been some small victories for those fighting for compensation for the Stolen Generations. In 2007, Bruce Trevorrow, a Ngarrindjeri man, successfully sued the South Australian government for his illegal removal as a child. With the help of prominent lawyer Julian Burnside QC, he won $775,000 in compensation. The SA Government appealed (although not against the payout), and lost.

Bruce died 11 months later, before knowing the outcome of the appeal.

The first state scheme to compensate Stolen Generations members – worth $5 million – was launched in 2008 in Tasmania, the Australian state that came closest to achieving a complete genocide of its First Peoples. Victims and their children were paid $58,000 and $5000 respectively.

In March 2016, almost a decade after losing to Bruce Trevorrow in court, the South Australian government finally launched a $6 million individual reparations scheme. It’s now closed, but was widely lambasted while open, with victims ultimately receiving just $20,000 in compensation, despite initially being promised up to $50,000. Lengthy delays in processing also meant advance payments of $5000 were rushed through because of the fear of people dying before they received any compensation.

NSW followed South Australia in 2016 with a scheme to make ex-gratia payments of $75,000 to Stolen Generations members. It was launched based on the recommendations of an inquiry led by ex-Greens MP Jan Barham (the same politician who pushed the NSW Government on the Stolen Wages scheme), and will close in 2022.

No other states or territories have acted in any meaningful way, and the best of the payments offered so far – from NSW – is still only half of what the Turnbull Government has put on the table for victims of institutional child sexual assault.

And yet, Aboriginal people have never stopped fighting for redress. As recently as last year – more than two decades after the delivery of Bringing The Home – there were renewed calls for the creation of a Stolen Generations compensation scheme to assist an ageing, frail population ravaged by past government practices.

On May 22, 2017, The Healing Foundation handed a report to Malcolm Turnbull. Its recommendations bare a striking resemblance to the scheme Turnbull is now pushing onto the states and territories to address the responses to institutional child sexual abuse.

Turnbull responded with $1.3 million for the Foundation to conduct research into exactly how many members of the Stolen Generations are still alive. Like all before him, he has thus far refused to commit to any financial compensation.

Double standards

While an unknown number of Stolen Generations members have died since the Bringing Them Home report, according to the interim research of the Healing Foundation, about 20,000 Stolen Generations members are still alive today. They have around 100,000 descendants who are directly affected – almost one-fifth of the nation’s Aboriginal population. In Western Australia – where there remains no scheme of redress – the figures are even worse. An estimated one in four Aboriginal children were taken, and today around 40 per cent of the Aboriginal population is directly affected by the removal policies.

As for the number of victims identified by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses To Child Sexual Abuse, it stands at around 3,000, with compensation payouts estimated to be as high as $770 million over 10 years.

In a twisted piece of irony, about 12 percent of the people who came forward to the Royal Commission were Aboriginal. They will, of course, qualify for Turnbull’s $150,000 compensation package, but it only exists because bad things happened to non-Aboriginal children as well.

It’s hard to fathom the different responses to the trauma endured by black children versus that endured by white children. But it is also undeniable.

When Stolen Generations members told their story, overwhelmingly they were not believed. Not by government, not by media, not by a majority of the Australian people.

It took 11 years to finally get a National Apology – boycotted by some politicians like Peter Dutton and John Howard, and lambasted by conservative commentators. And, after 21 years there remains no national compensation scheme.

As for Stolen Wages victims, they have to launch legal actions to get their stolen funds returned in full.

But for the victims of child sexual abuse at the hands of institutions, they were promised a compensation scheme 12 months before the Royal Commission’s final report was even produced, and a National Apology before the report has even been tabled in parliament.

When someone is harmed, there are three basic principles – universal tenets respected the world over – which all Australians expect simply by virtue of their rights as citizens.

They are: 1. An apology; 2. A guarantee that it will never happen again; and 3. The right to redress, which includes monetary compensation.

All three will rightly be afforded to the child victims of institutional rape, without delay. But we have denied – and continue to deny – two of those things to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (the number of Aboriginal children in out of home care today is double what it was in 2008 when the Apology was delivered).

The fact is Aboriginal people have never stopped fighting for justice – not for the Stolen Generations, not for the victims of the Stolen Wages outrages, and not for the theft of their lands.

They fight and resist just as we would fight and resist if these things happened to us. Just as the brave victims of institutional child abuse have fought and resisted.

All Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people want is what the rest of us get, but they’re fighting a nation that does not want to give. When you strip it bare and look at the facts, our country cares little for their pain and suffering, and has no genuine notion of basic equality.

We are not the land of the fair go, and we never were.

If #changethedate is a litmus test for the maturity of our nation, then our treatment of the Stolen Generations and the Stolen Wages victims is the test of our soul.

- Note to readers: Feature writing like this story is extremely time-consuming. The author – who Facebooks here and tweets here – does not get paid for his work. If you got something from this article, please consider giving something back by clicking on the donate button below, or subscribing to New Matilda, visiting our shop or subscribing to our FREE email digest. Sharing this story with family and friends also assists greatly.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.