As politicians and media play racialised politics with the lives of Melburnians, Michael Brull urges people not to forget the history of the police in how we actually got here.

Ever since the Victorian Liberals started ramping up the demonisation of “African gangs” in Melbourne – with the Federal Racist in Chief Peter Dutton quickly joining in – the response of progressives has been critical, but partly defensive.

The defensiveness has come in the form of conceding that yes, people of African descent are over-represented in some sorts of crimes in Victoria. However, the general crime rate is falling, and the over-representation is more or less accounted for by socio-economic disadvantage.

So take the standard statistic. People of Sudanese and South Sudanese background in Victoria make up 0.14 percent of the population, but are about 1.5 percent of the criminal population. It is concluded from this that Sudanese and South Sudanese immigrants are about 10 times more likely to commit various crimes.

Similar conclusions could be drawn about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. They make up some 2 percent of Australians over 18, but 27 percent of people in prison. In this case too, part of the over-representation can be attributed to socio-economic disadvantage. But the crime statistics themselves aren’t neutral. They are reflective of oppressive and discriminatory policing habits.

When people see that Sudanese people are over-represented in crime statistics, a red flag should go up that another racial minority is being heavily policed. We cannot know the extent to which the statistics are influenced by the nature of how police interact with Sudanese immigrants. But it is irresponsible and misleading to simply treat crime statistics as innocent and objective.

In the case of Aboriginal people, we already have extensive evidence from long studies about how police oppress and harass Aboriginal people. One such study was the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody. Another was the National Inquiry into Racist Violence.

The report chronicles at length “the extensive nature of racist violence by police”. For example, the Inquiry “found that 85 per cent of the 171 Aboriginal and Islander juveniles interviewed in Queensland, New South Wales and Western Australia reported that they had been hit, punched, kicked or slapped by police officers (85 percent in NSW, 90 percent in Qld and 94 percent in WA).”

The report went on to Finding 5: “Aboriginal-police relations have reached a critical point due to the widespread involvement of police in acts of racist violence, intimidation and harassment.”

At this stage, there has been far less investigation into police relations with Sudanese people in Victoria. But the evidence we do have is suggestive enough. Flemington and Kensington Community Legal Centre (FKCLC) has a Police Accountability Project, which has devoted a lot of resources to battling racist policing, from racial profiling to various police abuses.

In a 2015 report on racial profiling, they presented their key findings from talking to young people. They found that young men of colour have had various negative experiences with the police, and these experiences of “racialized policing” affected their mental health. They came to believe that there was a “lack of accountability” for police abuses.

Their conversations with Community Development Service Providers led to similar findings. Every worker spoken to disclosed “abuse or mistreatment by the police”.

Note: this report came out in 2015. In 2013, FKCLC settled a case with the police that made it all the way to the Federal Court over police racial profiling of African youths in Melbourne. Solicitor Peter Seidel observed that they were being “stopped and searched two-and-a-half times more than their population would suggest should be the case”. Furthermore, a University of Melbourne Statistician, Professor Ian Gordon, “found the young African men in this area commit significantly less crime; that’s contrary to what we’re hearing from Victoria Police.” Police agreed to conduct inquiries into multicultural training, and on their processes of stopping people and asking them what they’re doing.

In December 2013, ABC “uncovered details of a secret Victoria Police operation targeting young African-Australians in Melbourne’s inner north.” Known as Operation Molto, it began in 2006. Jeremy Rapke QC, the Director of Public Prosecutions at the time, who later represented the African youths suing the police, observed that “the police data which was available to us in this case, which was for a four or five-year period, clearly established the existence of racial profiling as a law enforcement practice in the Flemington/North Melbourne area at the relevant time. It’s racism, because what you are doing is you are targeting an individual based on his race rather than based upon any other legitimate policing criteria.”

The problem is not just police abuses and racial profiling. The problem is not just the perception that police aren’t held accountable for those abuses. It is also that that perception is basically correct.

In their 2017 report on police abuses and racial profiling, KFCLC observed that police “investigate their colleagues” when there are deaths in custody or allegations of things like racial abuse, assault, torture and so on.

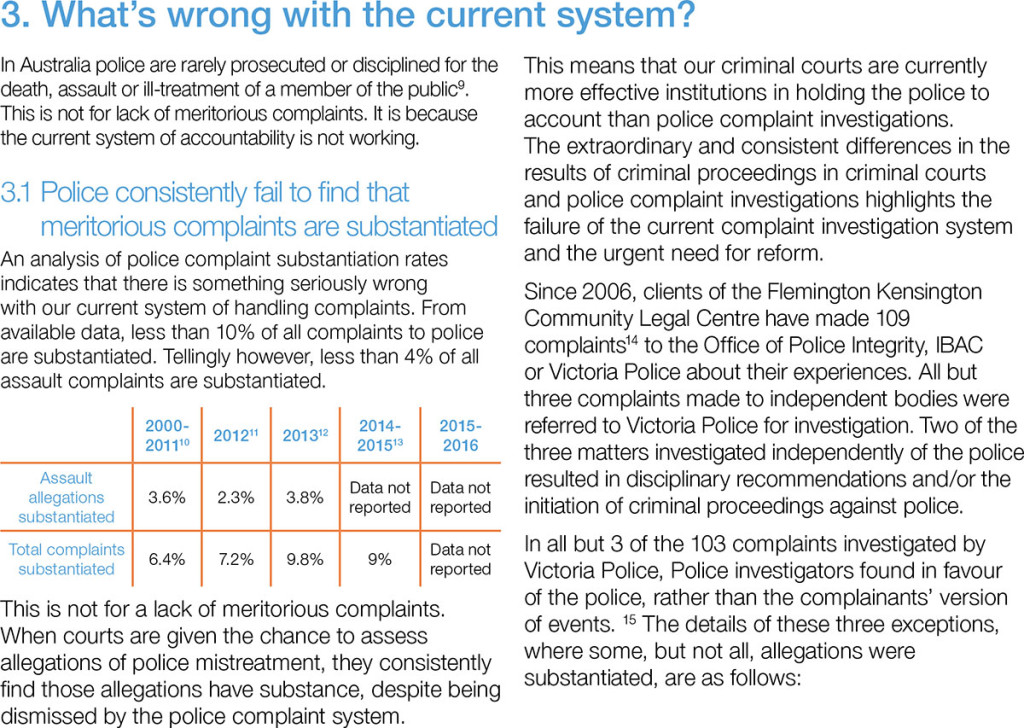

The result is that “police are rarely prosecuted or disciplined for the death, assault or ill-treatment of a member of the public. This is not for a lack of meritorious complaints. It is because the current system of accountability is not working.”

They found that less than four percent of all assault complaints are substantiated. Incredibly, “When courts are given the chance to assess allegations of police mistreatment, they consistently find those allegations have substance, despite being dismissed by the police complaint system.”

KFCLC has made 109 complaints about police misconduct to the Office of Police Integrity, Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission, or Victorian Police since 2006, when Operation Molto began. Almost all of the complaints made to the other two bodies were referred back to Victorian Police to investigate.

In 100 of 103 investigations, Victorian police found that the police had done nothing wrong. In the three exceptions, police accepted only the most minor allegations against police, whilst dismissing more serious allegations such as assault.

KFCLC provides case studies of some of its complaints, and they are deeply illuminating. In 13 criminal cases KFCLC has been involved in, judges have favoured the accounts of their clients over those of the police. The case studies offer illuminating examples of what this has meant, and are well worth reading. They give a clear idea of the difficulty in holding police accountable for racist violence and abuses.

Case studiesKFCLC observed that “at this stage all contested hearings involving clients who made an official complaint have resulted in judgements that contradict the police complaint investigation.” That is, the courts have proven time and again as the “the primary means of redress against police misconduct”.

At the time of writing, police have been regarded as an opponent of the racial bating of the Federal and Victorian Liberals. Victorian Police Commissioner Graham Ashton called Dutton’s comments about the danger of Melbourne “complete and utter garbage.” This has resulted in the strange and unfortunate position of progressives positioning the Victorian Police as some kind of voice of authority criticising racism, rather than a central institution in entrenching racial oppression.

Meanwhile, the Victorian Labor Acting Premier has responded to the outcry by assuring the public that, “We are going to tackle these crimes where they occur, we are going to tackle these gangs where they occur, we are going to throw the book at them.”

Throw the book at them is essentially the Victorian government confirming that they agree with the premises and conclusions of the Liberals. If the problem is African gangs, the solution is tougher policing. Whether policing is already tough enough hasn’t even entered the conversation. Whether police are part of the problem hasn’t even been considered. A political consensus has formed, from the Liberals and the right wing media, to Labor and Fairfax. If this consensus is institutionalised, as currently seems likely, we will see will be further entrenchment and escalation of racialised policing of people of African background.

Right now, political and media elites are a central part of the story. But we shouldn’t forget the traditional role that has been occupied by the police.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.