The myth of the moderate Malcolm Turnbull dies hard, writes Ben Eltham. Will 2018 be any different?

At the end of 2017, it was easy to think of the Turnbull government as a spent force. Given the constant state of crisis that has bedevilled politics for years now, we can be forgiven for thinking that the government is about to fall, or that Turnbull is about to be replaced.

That would be unwise. Politics is rarely predictable, and even if it were, the fact remains that the government is just 18 months into its second term. Turnbull doesn’t have to call an election until late 2019. As long as he can hold his government together, Turnbull has plenty of time. The longevity of the Turnbull government is one of the stranger aspects of Australia’s unsettled political economy.

The Coalition has ruled since September 2013, but really it has been two different governments: Abbott and Turnbull. You need to grasp that fact to understand politics in 2018. We are not in the fifth year of a unified Coalition government. We are 27 months into the Turnbull administration.

No-one could accuse the Abbott government of lacking a program: its agenda was obvious, as soon as it was elected. Commissions of Audit, massive cuts to health and education, endless culture wars, a jihad against climate science. Tony Abbott and his cabinet certainly stood for something. To their bemusement, it was a something that voters rejected.

Ever since he took office, media coverage (and to a lesser extent, popular understanding) of Malcolm Turnbull’s prime ministership has been framed around wishful thinking – the desire for a particular sort of prime minister, a prime minister that Turnbull has manifestly failed to be.

The idea of a small-l liberal, moderate, progressive Malcolm Turnbull has died hard in the mediascape, even as it has quickly faded in the imagination. Fawning admirers at Fairfax and the ABC fell over themselves to genuflect in front of a politician that could not help but identify with (the conservatives at News Corporation were a different matter).

Perhaps the paradigm example of the media love-in was when Turnbull ushered Annabel Crabb around the family mansion on Sydney Harbour; but there were plenty of others. When Turnbull announced his ill-fated ploy to call a double-dissolution election, commentators gushed.

In general, many in the mainstream media found themselves invested in the idea of Turnbull as a centrist saviour of Australia’s broken political process, with little more evidence than the fellow-feeling of a similarly privileged class. The moderate image was fed by the man himself, who positioned himself successfully as a kinder and gentler Liberal, a wearer of leather jackets, a supporter of same-sex marriage, and a believer in action on climate change.

As we know now, he was none of those things. Malcolm Turnbull no longer supports action on climate change. He barely bothered to campaign on marriage equality. The famous leather jacket is missing at the dry cleaners.

Malcolm Turnbull fooled many into believing he was a moderate. But he was lying. Malcolm Turnbull is not a kinder, gentler conservative. He has not been a moderate prime minister. He is a wealthy lawyer and businessman whose main policy commitment appears to be to staying in power.

Turnbull’s government has been right wing in almost every significant respect, and the hopes for a small-l liberal, moderate and centrist government entertained by voters and journalists alike have been dashed. The evidence is impossible to ignore: Turnbull is a ruthless opportunist who shows little scruples in his dealings with colleagues, with civil society, or with ordinary citizens.

27 months of government has shown us that what Malcolm Turnbull ultimately cares about is power: gaining it, holding it, and finally using it, in the interests of the ruling class to which he demonstrably belongs.

In the years since rolling Tony Abbott, media rhetoric has focused on Turnbull’s metric of 30 losing Newspolls as the reason why Abbott had to go. Perhaps they should re-read the transcript of that first media conference. Turnbull promised a “thoroughly Liberal government committed to freedom, the individual and the market.” In that respect, at least, he has been true to his word. Turnbull has delivered on his promise as a capital-L Liberal. His government has indeed been one committed to economic freedom, to individualism, and to the supremacy of the market.

How do we know this? Because of the policies Turnbull has implemented.

In this article, I will examine five key policy areas: climate and energy, housing, industrial relations, tax and social policy. In each of these policy areas, Malcolm Turnbull’s government has been conservative and neoliberal. It has governed in the interests of the rich and powerful, rather than ordinary citizens. It has been, in Turnbull’s own words, “a thoroughly Liberal government.”

1. Climate and energy

Exhibit A is a lump of dead coral. There are hundreds of kilometres of dead reefs all the way up the Queensland coast.

2016 bleaching on #GreatBarrierReef published this week in Nature. Red; 60-100% of colonies bleached, Orange; 30-60% pic.twitter.com/LLLn33qHJn

— Terry Hughes (@ProfTerryHughes) March 18, 2017

In decades to come, when the politics of the moment have faded, this will be the true legacy of the Turnbull government. What could better sum up its petty mendacity than the death of a natural wonder, to the cheers of a coal-fondling Treasurer? Similarly, nothing could better illustrate the indifference of Australia’s political classes to their larger responsibilities than the shocking death of large swathes of the nation’s largest biological organism.

Historians will record that at the same time devastating bleaching was killing a tourism industry worth 70,000 jobs, Coalition ministers were glad-handing a lump of coal in federal Parliament.

2017 was the year when the government’s threadbare arguments against renewable energy were shown up for the lies they always were. A series of detailed reports by the Australian Energy Market Operator showed the South Australian blackout of 2016 was caused by a cascade of faults beginning with a storm falling transmission lines – not renewable energy, as the government had wrongly claimed.

Cynicism barely begins to describe the dead-eyed psychopathy of the Coalition’s position on energy. Despite talking incessantly about energy security throughout the year, the government has done precisely nothing to reform Australia’s energy system. The risible example of the Liddell power plant in New South Wales perfectly illustrates this point. In their bid for cheap media headlines, the government postured on the closure of a clapped-out hulk.

The Liddell controversy was the purest conservative theatre, allowing the government to gesture and preen about its fossil fuel credentials, even while its owner AGL calmly put together a replacement plan based around renewable energy.

For all the jawboning, in the end the government has not forced AGL to keep Liddell running. In fact, the government has not done anything at all in energy policy: a year after the delivery of Alan Finkel’s energy report, the government’s risible response is nothing but an eight page brochure.

There is no contest in Australian energy markets: renewables have won. The days of coal are coming to an end, and no amount of Parliamentary grandstanding can change that. Prices for wind and solar keep falling; decrepit old coal plants keep breaking down. The rapid and convincing success of South Australia’s new 100MW Tesla grid battery is the most mediagenic example: after ridiculing the South Australian government for its energy policy, the federal Coalition has been forced to watch on with gritted teeth as the southern state has made good on its energy infrastructure promises.

Of course, energy policy is not really about the future of Australian energy system, at least not for the government. It is instead about the internal politics of the Liberal Party, and the donors to that party in the resources sector. For reasons that have nothing to do with the environment, and everything to do with ideology and money, energy and climate have become litmus tests for conservative doctrine.

Chest-puffing symbolism has become more important for the conservative faithful than any meaningful engagement with the real world, which is heating up rapidly and endangering the future of our children and grandchildren. The real world is also rapidly transforming its energy system. The myopic and stupid figures at the nexus of money and power in the Liberal Party are blind to this reality. But it is happening anyway.

In the meantime, Australia’s carbon emissions are rising. They are rising because the Turnbull government wants them to. That’s what happens when you abolish a tax on carbon, and refuse to regulate against fossil fuel pollution. That’s what happens when your entire energy policy is anti-renewable, and pro-coal. Rising emissions are Coalition policy.

2. Housing

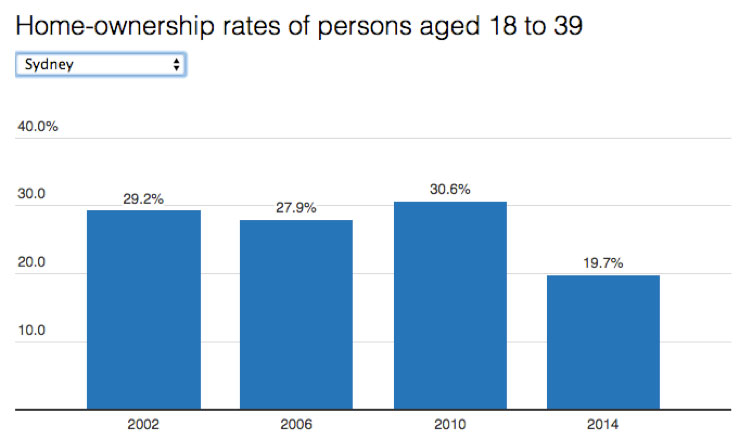

Housing is another example of the Coalition’s willingness to ignore the national interest, in favour of the special interests of Liberal party donors and power-brokers.

Suburban real estate agents have always been the Liberal Party’s true believers, and that has never been truer than today, when housing in Australia’s capital cities has been transformed into a kind of sick joke at the expense of an entire generation.

In just a few short years, the entire social fabric of a home-owning nation has been thrown on a bonfire of property speculation, and millennials paying $250 a week for a dingy room in a run-down share house know it.

The rent rage is filtering up rapidly into the middle classes, where university repayments and job insecurity are interacting with sky-high rents and the contempt shown by landlords for tenants to produce a combustible social situation.

Forget about a housing crash: the really scary scenario is if prices keep rising. Gen Ys may not be erecting barricades just yet, but they should be.

The stratospheric rise in house prices in Australian capitals has benefited a class of landlords and property developers at the expense of nearly every younger and poorer person in the nation. But our political class simply doesn’t care… probably because they all own houses.

Some of them own quite a lot of houses. Most of them take donations from the property sector, especially in the Liberal Party. This is how politics in Australia works.

Housing is a social volcano that Australia’s elites are happily growing tomatoes on, even as the mountain belches and rumbles. The malaise was summed up by the schadenfreude of a Labor federal MP unable to afford a house in his own electorate. That seat is the rapidly gentrifying electorate of Wills in inner Melbourne, which only a decade ago was still composed of predominantly working class suburbs like Brunswick and Coburg. But few workers in the seat of Wills own houses now. They rent, because they have to. It would be funny if it wasn’t the fate of an entire generation. It would be funny if it didn’t make you cry.

3. The workplace

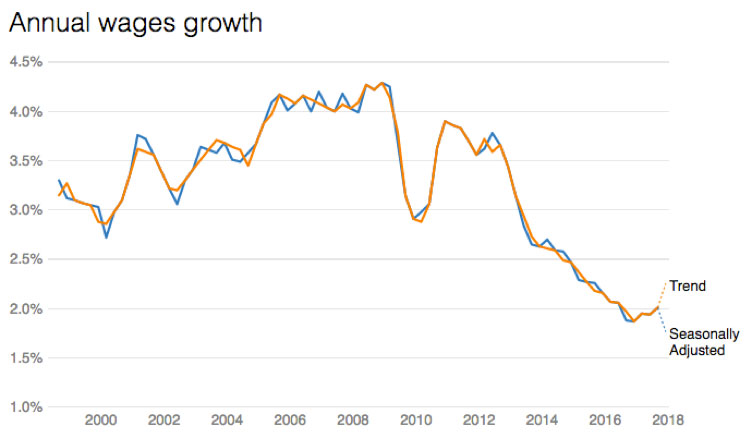

On industrial relations, the government continued its ideological assault on organised labour, despite all the evidence suggesting that Australia needs stronger trade unions, not weaker ones. With wage growth at its lowest in two decades, the government has none-the-less continued to march to the tune of big business, cheering when the Fair Work Commission reduced penalty rates – and therefore wages – for many of the nation’s lowest paid workers in the retail and hospitality sectors.

Trade unions are far from perfect institutions, as the Health Services Union scandal demonstrated. But they remain the only significant countervailing influence in modern society that can curb the power of capital. Big business is on a triumphant march towards ever-lower wages and conditions, and at the moment there is little to stop it.

Four years of Coalition government have revealed disastrous flaws in the industrial relations architecture bequeathed by the Rudd-Gillard government, at least when it comes to protections for workers. Rather than repeal the Fair Work Act, the Abbott and Turnbull administrations have instead stacked the Fair Work Commission with pro-business commissioners, which explains bizarre decisions like the cut to penalty rates announced this year.

With the right to strike now essentially outlawed in Australia except under very particular circumstances, the ability of organised labour to exercise its most effective tool has been radically circumscribed. The results are showing up in the economic statistics: strikes are at near record lows, wage growth is actually declining in real terms, while profits are riding high.

If you need an explanation for the rising income inequality in Australia, the growing imbalance between the power of capital and labour is probably the best.

When it comes to the economy, the government might be forgiven for tooting its horn. Scott Morrison certainly is. According to most economists, including those at the Reserve Bank, the economy is improving. Unemployment is trending downwards, economic growth is sustained, and inflation is low. Business conditions are robust and full-time work is growing at its fastest rate in a decade.

In general,given these macroeconomic conditions, you’d expect people to be pretty happy. Why aren’t we? Probably because our pay packet is barely growing.

The current zeitgeist doesn’t feel like a boom. Wages are bumping along the bottom, even while the economy grows. Energy costs are high, and housing costs sky-high, but wages aren’t keeping up. Work is increasingly insecure. That puts a floor on the everyday ambitions of ordinary workers.

What the economy really needs is a broad-based pay rise, and a labour market where workers have some bargaining power. But we’ve got the opposite.

The world of work is always important, and in in 2018 it is perhaps the most important policy sphere now returning to the forefront of the political debate. The Coalition is often derided as a do-nothing government, but no-one could accuse employment minister Michaelia Cash of inactivity. The gung-ho Minister for Jobs and Innovation has been relentless in her pursuit of a pro-business workplace. Cash has spent the majority of her time as employment minister busting unions, although not always effectively.

Cash faced many embarrassments last year. Most notoriously, of course, she was embroiled in controversy when her office tipped off the media about an Australian Federal Police raid of the Australian Workers Union. That raid, a damp squib as it emerged, was called in to media newsrooms before the AWU itself found out, and before the police even arrived.

Turnbull was far from worried. Instead he backed Michaelia Cash to the hilt. It’s a measure of the centrality of union busting to the Turnbull government’s agenda that Cash has been promoted in the recent cabinet reshuffle, gaining in seniority and respect. Cash is widely admired within the Coalition for her take-no-prisoners political style, and for her single-minded dedication to destroying the power base of organised labour in this country.

And Cash has been more successful than the union movement would like to admit. Despite a resurgent campaign from the ACTU’s charismatic Sally McManus, the reality is that union power in Australia is at a post-war low, and shows little sign of reviving. Just seven per cent of Australians under 24 belong to a union. Most Australian workplaces are profoundly insecure places, even for employees enjoying the protection of full-time employment. Only a minority of Australian workplaces are unionised, and unions now lack essential weapons like the legal right to strikes and secondary boycotts.

The neoliberal revolution has been most successful in the workplace, where most employees now find themselves ruled by a management ethos that recognises few precepts other than the maximisation of profit. Contract-based employment is common: white-collar workers often find themselves rotating through a series of 6- and 12-month contracts, while the remnant blue-collar workforce is frankly and openly exploited, via labour hire companies and out-and-out wage theft, as we’ve seen in the 7-Eleven scandal.

Casualisation is high, and has been for some time. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there are 2.6 million Australians working in jobs without paid leave, the main measure of casualisation. Australia is one of the most casualised workforces in the industrialised world.

One of the Coalition’s most successful tactics in workplace relations has been bench stacking at the Fair Work Commission, Labor’s Gillard-era industrial umpire. Taking a leaf out of the US Republican Party’s playbook, Eric Abetz and Michaelia Cash have worked diligently to appoint anti-union commissioners to the Fair Work judiciary; one recent appointment is Sarah McKinnon, a former workplace lawyer for the National Farmers Federation.

In summary, it’s no wonder the Coalition is so pleased with Michaelia Cash. She’s winning.

4. Tax

Federal treasurer Scott Morrison, delivering his 2017-18 budget speech.

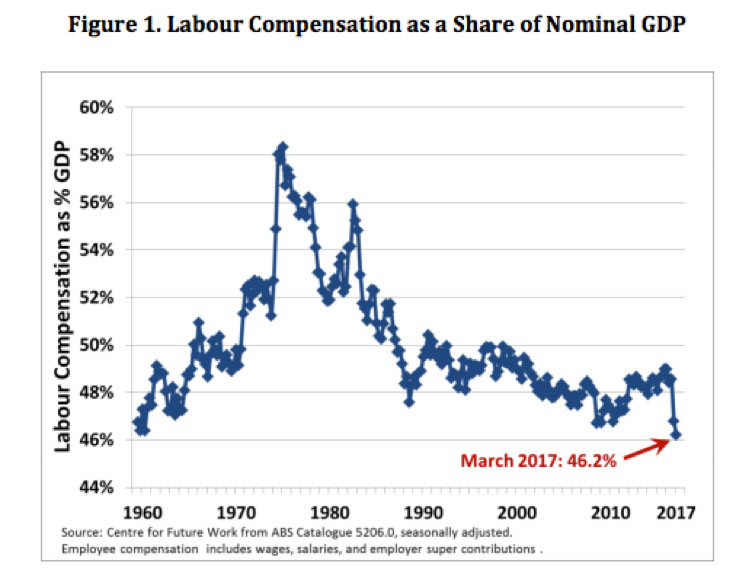

And then we come to tax. Tax is one policy where the government likes to claim credit. After all, it represents one of the few legislative victories that the Turnbull government can point to. Cutting company tax was the centrepiece of the Coalition’s disastrous 2016 election campaign, when a nimbler Labor ran rings around a leaden-footed government by focusing on health policy.

While Labor screamed “Save Medicare!”, the Coalition tried to convince voters that cutting taxes to big corporations would somehow make us all richer in ten year’s time. It was trickle-down with the emphasis on the trickle, even while the share of the economy devoted to wages fell to a five-decade low.

But the government was re-elected narrowly, and it was able to get some of its company tax cuts through. The result was a roughly $24 billion hit to the budget, even though the budget is in deficit. Budget emergency? Not for the owners of businesses.

Just how little tax Australia’s big corporates pay still beggars belief. As the indefatigable investigative journalist Michael West notes, recent data released by the Australian Tax Office just before Christmas shows that “354 of Australia’s biggest companies have now paid zero tax in three consecutive years on a combined total income of $911 billion”. That’s nearly a trillion dollars of revenue for no tax. Meanwhile, ordinary PAYG tax is up. No wonder voters are cynical.

When you probe the data, it’s pretty obvious we’re all being fleeced. Notorious international commodities giant Glencore booked $22.4 billion in income in Australia in 2015-16. It paid no tax. Not a cent. Qantas booked $15 billion. No tax. Not a cent. Origin booked $12 billion. No tax. Not a cent.

The list goes on and on. Energy Australia: $7.8 billion income, no tax. Exxon: $6.7 billion income, no tax. British Gas: $6.2 billion income, no tax. Toll Holdings: $5 billion income, no tax. Bluescope Steel: $4.9 billion, no tax. Vodafone: $4.2 billion, no tax.

Does anyone truly believe this tax avoidance is legitimate? It may be legal to the letter of the law, but the law allows loopholes the size of super tankers to be sailed through. Lax regulators and clever tax accountants at the big four accounting firms have created a system where company tax is largely a voluntary contribution, rather than a legal necessity.

All this missing company tax matters, for obvious reasons. It is tax revenue that is not available to fund schools, hospitals and roads. Just as importantly, the foot-loose and barely regulated nature of corporate profits is a key driver of inequality, as the owners and top executives of big companies amass vast stores of wealth, apparently immune from the purview of national tax offices. While welfare recipients face ever-harsher crackdowns, the corporate titans are calling for more tax cuts from their seaside regattas.

5. Social policy

And that brings us to social policy, where the Turnbull government’s hard-line credentials are most stark.

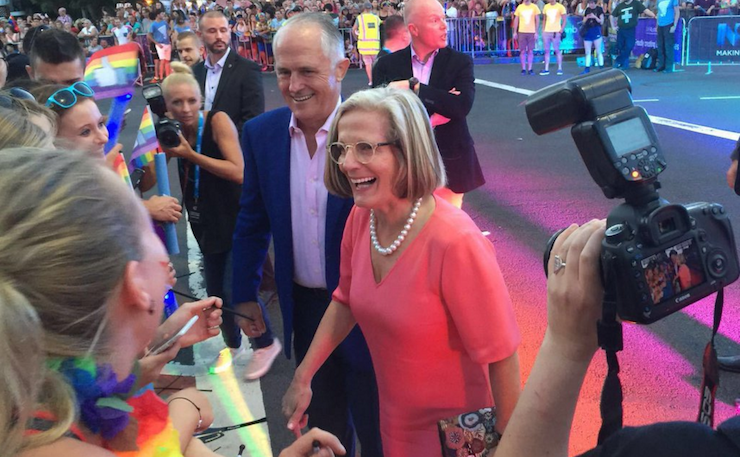

The year’s seminal political event was the successful passage of marriage equality legislation. On the face of things, the Prime Minister could be given some credit for ushering through the legislation after the victorious postal survey.

Few LGTBQI Australians seem to be thanking Turnbull, however. The marriage survey, while ultimately successful, revealed deep divisions in Australian society. It exposed tens of thousands of Australian families to vicious prejudice and hate. Instead of leading from the front, as we should expect from the elected Prime Minister, Turnbull followed along behind the culture warriors on the Liberal right wing. He did little in the survey campaign, and nothing to quiet the deep reservoirs of hate in his own party.

Almost everything about the marriage survey was designed to maximise the collateral harm to LGTBQI Australians. The final result, a victory for tolerance and equality in the face of breathtaking political cynicism and contumely, was also an apt metaphor for a political class far more obsessed with its own machinations than the national interest, or the welfare of ordinary voters.

And it is when we turn to welfare that the government’s contempt for the needy and unfortunate in Australia was most obvious. 2017 was of course the year of Robodebt, a cruel and error-prone algorithm that imposed welfare debts on tens of thousands of ordinary Australians, often falsely.

I spent the first six months of the year reporting on the Robodebt debacle; it remains one of the worst examples of public policy dysfunction in recent Australian history. The problem with the seriously broken Robodebt algorithm wasn’t just that it was frequently wrong – the true problem was that the government and its key bureaucrats at the Department of Human Services knew the system was broken, and implemented it anyway.

The scandal and opprobrium was brushed off by the truculent ministers responsible, Christian Porter and Alan Tudge. They dismissed it for a very simple reason: as the testimony to the Senate Inquiry into Robodebt made clear, they wanted the system to punish welfare recipients. When blogger and economist Andie Fox wrote about her experience, the Department responded by revealing her personal case file details to a Fairfax journalist.

Robodebt was the logical extension of the Coalition’s genuine beliefs about those in our society unlucky enough to receive government benefits: that their poverty is a symptom of their failures as human beings.

Of course, Robodebt wasn’t the only aspect of social policy where the government punched downwards. Whenever it spotted a disadvantaged group that it judged unlikely to fight back, it attacked them. That was why we saw more attacks on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders; more attacks on asylum seekers, and as 2018 began, a new scare campaign about fictitious ‘African crime gangs’ in Melbourne.

Can we stop calling Malcolm Turnbull a moderate?

It shouldn’t have surprised anyone when, on New Year’s Eve, Turnbull waded into the racist beat-up about ‘African crime.’ Cynical opportunism like this is entirely in keeping with his government.

Malcolm Turnbull’s chameleonic character has blinded many to the central aspects of his biography: inherited wealth, a precocious, unscrupulous talent, and a career spent circling the nexus of money, media and power. Journalism, then the law, then merchant banking, then politics: this is a life history characteristic of a politician whose instincts and policies are opportunistic, acquisitive and reactionary.

True, Turnbull is not Tony Abbott. But no-one is. Turnbull’s factional position to the left of the warriors in the Liberal right wing has helped to distract from what should now be obvious: Turnbull is a representative of capital. He rules for the rich, not just because he is rich, but because he believes in wealth as a motive force in his political philosophy. He is a politician that would have been perfectly at home in the government of Robert Menzies or Joseph Lyons.

In summary, Turnbull is neither a moderate nor a centrist. He is a conservative, as his actions as Prime Minister have shown.

Clocking Turnbull as a conservative dissolves the confusions that have clouded commentary of his government ever since he assumed office. The right of Australian parliamentary politics has taken many forms, and has enjoyed several party configurations. But, as the historian Judith Brett reminds us, it has always been united in one goal: keeping Labor out of office.

Judged on this metric, the Turnbull government is doing just fine. The great thing about the “keep Labor out” position is that you don’t necessarily need a robust policy agenda of your own. Keeping the ALP out of office is the main thing. If you can deliver some tax cuts to business along the way, so much the better.

If we frame the Turnbull government as a normal Tory government in the Australian system, its strange torpor makes a lot more sense. The major policy debates of 2017—energy, housing, tax, industrial relations and social policy – all show the government’s desire to rule in the interests of capital, and against the interest of workers.

So if there’s one thing to hope for in 2018, it’s that we finally see Malcolm Turnbull for what he really is.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.