In the fourth in a five part series on the proposed Adani Carmichael coal mine, John Quiggin looks at the numbers for the project, and like virtually all other parts of the planned project, they don’t survive closer examination. John Quiggin explains.

In what was lauded as a landmark moment for the Adani Group, in June 2017, its chairman Gautam Adani announced his board had given final investment approval for the $5.3 billion first stage of its Carmichael mine project in the Galilee Basin, as well as approval for the associated rail line project, to be constructed from the Basin to the Abbot Point coal terminal.

At the same time, however, Adani asserted its project’s future would remain contingent on finance. Given the projects’ outstanding financial issues, exposed in detail here, alongside Adani’s sustained failure to reach agreement with Traditional Owners, which undercuts the legal basis and legitimacy for this mine to proceed on W&J Country, its future remains uncertain.

Seven years since Adani Mining Pty Ltd. – Adani’s Australian arm – moved into Australia when it secured coal tenements, it has neither financial nor legal close for its proposed Carmichael mine.

These are the shaky grounds on which W&J are expected to forego their rights, assume the destruction of their country, and be grateful for a tiny sliver of the pie.

Yet the rhetoric of 10,000 jobs and great social advancement that would flow from the supposed benefits of the project to Traditional Owners along its corridor, and especially the W&J on whose country the mega mine will operate, is a far cry from that which Adani has actually put on the table.

A preliminary analysis commissioned by the W&J Traditional Owners and presented to the claim group meeting on 2 December shows what a miserable proposition Adani’s proposed deal is for Traditional Owners.

Adani is offering Traditional Owners just 0.2 percent of its total revenue; far below industry benchmarks that indigenous groups should get 0.35 – 0.75 percent.

To put this in perspective, even if Adani doubled what was on offer, it would still only be equivalent to some of the lowest Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) deals in Australia.

The deal on offer is also out of balance in terms of the kinds of economic opportunities it will afford Indigenous communities; with primary focus on highly speculative job opportunities. Seventy-five per cent of Adani’s benefits package is wrapped up in jobs; and yet if the jobs don’t come, the purported benefits will simply not be realised.

While the economics of the mine represent a very poor deal for Traditional Owners, they are at the same time expected to cop the brunt of the costs – including destruction of country – for the mines go ahead.

State Developmentalism

Yet such inequality is par for the course. For most of the 20th century, Australian policy regarding land use was dominated by the ideology of developmentalism which started with the doctrine of terra nullius, dispossessing the Traditional Owners of any rights they might claim, and obliging settlers to develop the land for agricultural and mineral commodities.

Despite its obsolescence, the developmentalist ideology maintains a powerful presence in Australian politics, almost invariably combined with hostility to Indigenous rights and environmental protection, alongside a nostalgic view of the 20th century industrial economy.

A particular feature of Australian developmentalism was the priority given to mining over agriculture and other land uses.

The political outcome was one in which, unlike in most other common law jurisdictions, mineral rights were not held by landowners but by the state, which in turn assigned them to any miner who could make out an appropriate claim. The preferential treatment of miners has continued to the present with Adani the latest example of a company praised and advanced by the state.

Developmentalism and preferential treatment remains influential under the returned Queensland Labor Government, particularly when faced with the potential but spurious benefits of large projects like the Adani mine.

The Queensland government offered financial inducements to Adani, including deferring payment of royalties, under the condition these would be repaid with interest at a later date. The full details of this royalty deal remain, ironically, hidden behind an opaque ‘transparency policy framework’.

Local governments have also been persuaded to offer unprecedented financial inducements. In return for a commitment to be used as bases for ‘fly-in fly-out’ workers, the Townsville and Rockhampton councils offered to contribute at least $15 million each for the construction of an airstrip at the Carmichael site, hundreds of kilometres from their jurisdictions.

Around $900 million of the required finance for Adani’s mega mine project could be derived from a loan requested from the Australian Government’s Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF). Until the recent Queensland election, this was supported by the Labor Government – though this is a proposition most Australians oppose, and one which became a decisive Queensland election issue. The re-election of the Labor government, with a promise to veto NAIF funding for Adani appears to imply that this funding option has now been closed off.

Even with financial breaks from government, the evidence – drawing from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) and other recent figures – demonstrates the Adani mine-rail project is highly unlikely to be economically viable. On this basis, any public money lent to the project, whether through the NAIF, or through a deferral of royalties, is unlikely to be recovered.

Movements in coal prices and exchange rates since 2015, alongside India’s shift away from coal – the primary intended market for Adani’s coal exports – all point to the (non)viability of Adani Mining Pty Ltd’s proposed project.

Even if the decline in coal prices that is anticipated in futures markets fails to occur, and Adani were to pursue its scaled down ‘Stage 1’ proposal – an unlikely best-case scenario for the industrial giant – it is still unlikely to deliver returns sufficient to allow repayment to lenders and investors.

These economic conditions facing Adani Mining, alongside W&J’s rejection of a land use agreement, render its Carmichael mine and rail project unviable.

Global Coal Prices

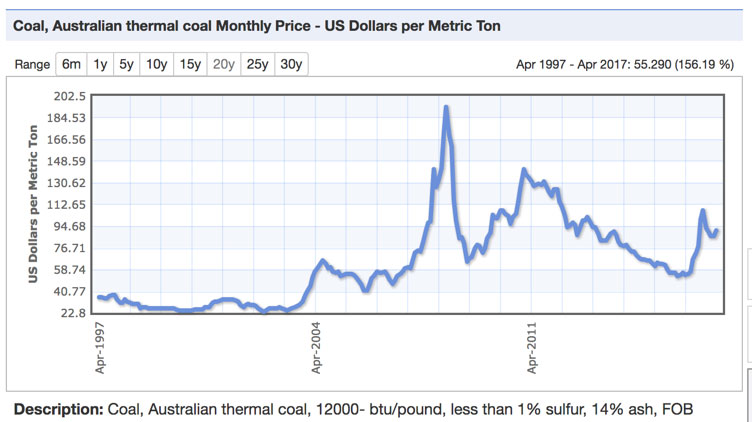

Coal traders have had a dramatic ride over the last decade or so. Between 2005 and 2011, world coal prices rose from around $US50/tonne to $US130/tonne. By 2011, when Adani Mining purchased the Carmichael mine lease, there was an expectation of further increases, driven by rapid growth in demand, particularly from India and China.

However, rapid reductions in the use of coal-fired power in Europe and North America, combined with a slowdown, and then a decline, in Chinese coal consumption, produced a steady decline in coal prices.

For Adani, it was a case of bad timing.

Coal prices have recovered considerably since 2016; driven primarily by Chinese Government policy, which has led to the closure of nearly 3,000 coal mines out of a total of 8,000 that were operational in 2012. The China National Coal Association estimates a further 1,000 mines will be closed during 2017.

The aim of this national policy was partly to close smaller, more dangerous mines, and partly to maintain the economic viability of remaining large mines. More broadly, China’s long-term decline in coal consumption is also tied to its policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions and local air pollution. Despite these policy settings, the long-term trend remains subject to fluctuations, including being tied to the availability of alternative fuel supplies, such as hydroelectric power.

As part of its interventions across the coal sector, China’s government also issued an order that limited mines to operating a maximum of 276 days per year. This turned out to be a severe overcorrection that drove a tripling in the price of coal in a matter of months. While the subsequent relaxing of this order in late 2016 dropped prices, they remain well above the early 2016 levels.

As it stands, the Chinese government appears to have stabilised on a path to reduce coal output gradually, and maintaining prices at around $US 75/tonne, with major implications for the global coal industry.

India Shifts Away from Coal

In the face of turbulent coal markets, Adani representatives have asserted the world price of coal is irrelevant to the viability of their Australian project, as the coal derived from the Carmichael mine is intended to be sold to other listed enterprises within the Adani group, including those based in India.

The significance of the Indian market for Adani has been backed by political rhetoric that posits coal imports will be crucial in providing access to electricity for hundreds of India’s ‘energy poor’. This rhetoric has been widely deployed by State and Federal Government Ministers in Australia as part of their championing of the mine, including positioning anti-coal activists as denying the right to livelihoods of the poor.

Yet the assertion that Adani’s vertically integrated network – that spans the entire coal life cycle, thereby enabling the industrial giant to act independently from global markets – stands in contrast to developments in India.

The Indian government has, for example, pursued a policy of import replacement in energy, with particularly strong support from Energy Minister Piyush Goyal. India’s policy of ending coal imports has focused primarily on publicly owned generators. It now appears possible that imports by public generators will fall to zero in 2018.

At the same time, numerous proposed coal plants, including some proposed by Adani, have been cancelled. This largely reflects the rapid reduction in the cost of solar photovoltaic (PV) power in India, which has rendered new coal-fired power stations uneconomic in most cases, thereby driving a decline in capacity utilisation for existing plants.

Adani Changes its Plans

In the context of shifting policy settings and coal markets, Adani has changed its plans. The original Adani proposal involved production of 60 million tonnes of coal from W&J Country in the Galilee Basin, and with an expected life of 90 years.

This was at first downgraded to 40 million tonnes of coal by 2022, with an expected life of 60 years, and then further reduced to 25 million tonnes of coal.

This revised so-called ‘Stage 1’ project would defer expansion of the Abbot Point terminal, alongside establishment of an initial, smaller mine.

Given the very unlikely possibility that coal will actually be in demand for electricity generation beyond 2050, the difference in duration is immaterial. However, these reductions in scale do have important implications for the viability of the rail line.

Capital investment for the life of the original mine project was expected to total US $21.5 billion. This total figure continues to be regularly cited, despite the significant downsizing that has since occurred.

Adani has, to date, invested approximately US $3.5 billion in this project, of which approximately US $2.1 billion financed the purchase of the Abbot Point T1 coal terminal. The remainder was associated with the acquisition of the Carmichael mine site.

A large portion of Adani’s total investment is what economists like to call ‘sunk’: that is, it is investment that would be written off if the Carmichael mine project failed to proceed. The only terms in which Adani could recoup these funds was if it could find a buyer for its assets. Adani’s unwillingness to write off such a large investment is likely one reason it has persisted with the project.

But the Numbers Don’t Stack Up

With its new scaled down project proposal, alongside global coal price fluctuations and the very real market access challenges in India, and elsewhere, just how do Adani’s numbers stack up?

Let’s start with estimates on the sale price for Carmichael coal.

As of October 2017, the price of Australian thermal coal was approximately $US97/tonne. Futures markets predict a decline in this price over coming years. Reflecting this trend, the futures price for delivery in February 2020, a possible start date for shipments from the project, is $US81/tonne.

However, Tim Buckley of IEEFA has estimated that the lower quality of the Carmichael mine’s coal output will result in a 30 per cent discount in revenue per tonne.

On this basis, the price of coal from the Carmichael mine – assuming exports begin in 2020 – will deliver just $A74 tonne.

But what will it cost to produce?

In its original analysis, Adani – based on advice from McCullough Robertson in January 2015 – estimated costs of US $38.70/tonne, although other analyses suggest the cost may be higher.

Significantly, this figure does not include the costs of rail transport and ship loading. And of course, such figures fail to capture the environmental costs of Adani’s proposed mega mine nor do they measure the irreplaceable loss of Country for Traditional Owners if this mine were to proceed.

Putting these ‘externalities’ aside, this suggests a cost of A $50/tonne in 2015, or $A55, updating for inflation at an annual rate of 2 per cent.

Based on these figures, the price for Carmichael coal – net of all operational costs – would be approximately $10/tonne. If royalties were paid at the standard rate, the net return would be just $3/tonne. That’s a very small return for the destruction of Country and walk over of Traditional Owners rights.

Adani has proposed a package to support Traditional Owners – a kind of quasi compensation for destruction of Country – including a $250 million Indigenous Participation Plan for the Traditional Owner groups along it’s project corridor, and the wider Aboriginal community of Central Queensland.

The details of this, however, have been described by W&J as a parlous deal. Demonstrating this, W&J draw attention to the very limited job creation. And on the basis of figures provided by Adani, Traditional Owners employed by the mine would be paid just $35,000.00 per year, a figure that barely meets Australia’s minimum wage.

This plan on offer is no exchange for the losses of land and waters, cultural and self-determination that W&J would incur; which is why they remain resolute in their opposition to the proposed mine. They alone are expected to give up their ancient legacy and birth rights so that others can benefit.

W&J has every right to object to the mine and refuse consent.

Cash Cows Are in Short Supply

On the basis of these shaky numbers, commercial banks have been reluctant to offer finance to the Adani project. Demonstrating this, 12 major global banks and three of the four main Australian banks have taken the unusual step of announcing that they will not lend to the project. These announcements reflect a combination of several judgements.

Firstly, it reflects that the project cannot be expected to generate returns sufficient to service its borrowings. In view of the warnings by financial regulators about the risks of stranded fossil fuel assets, a failed loan to a project of this kind could also result in a judgement that the banks concerned had violated prudential requirements.

In addition, given the political toxicity of the project, the reputational risks facing banks were best managed by an explicit announcement that the project would not be funded.

Given the difficulties of attracting commercial loans, the Adani project has relied heavily on the prospect of support from governments, or government-backed financial institutions.

The most important of these, discussed already, has been the prospect of financial support from the Commonwealth government, through the NAIF or from equity investment by state governments. Neither of these now appears likely.

But there are also a number of other major contenders.

Amongst these is included export-import banks. Adani’s proposal originally involved Korean steel firm POSCO, which raised the possibility of support from Korea’s Eximbank. The relationship with POSCO has, however, now broken down, with Adani arranging to source steel from Arrium in Whyalla; and making its announcement to do so to coincide with the amendments process in Native Title legislation in May 2017.

Accidently referred to as the ‘Adani bill’ during debate in the Senate, these amendments were tied to, as Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull assured Adani, ‘fixing’ the native title problem to ensure the mines go ahead.

Adani’s decision to support an Australian steel worker could be read as a strategic ploy to build its social license during these legislative reforms.

Adani is also looking to The State Bank of India (SBI) for financial support. A loan of $1 billion was announced in 2014, although this was later revealed to be a non-binding memorandum of understanding.

SBI finance remains a possibility, but the likelihood has declined, particularly because SBI is increasingly burdened with non-performing loans.

Vendor finance from the Chinese Government controlled China Machinery Engineering Corporation may also financially back Adani, including for the provision of equipment for the project. The Australian Government has offered its assurances that Adani’s Carmichael mine has achieved all its approvals, and on this basis represents a viable investment proposition.

The Federal Government, through Barnaby Joyce and Steve Ciobo, has also advocated directly to the Chinese Government for financial support – citing the ‘fixing’ of native title as a key impediment removed.

But in recent days, major Chinese Government controlled companies are reported as backing away from Adani’s bid for finance and equity. This further demonstrates that neither coal, or Adani, are secure investments.

If It’s Not Viable, Why Would the Project Proceed?

The analysis above shows that, even under highly favourable assumptions, the Adani Carmichael project will be unable to generate sufficient returns to cover interest at commercial rates, or to repay capital to lenders and investors.

This analysis therefore raises the question; why does Adani Enterprises choose to proceed with such a project?

Three possible answers present themselves.

The first is that Adani does not in fact intend to proceed with the project in the near future. Rather, the project is being kept alive with relatively modest expenditure to avoid writing off the large amounts already invested, and to maintain an option in the hope that ‘something will turn up’, such as an unexpected and sustained increase in the price Adani can realize for coal.

A second hypothesis is that the complexity of the Adani corporate structure is such that Adani could construct the proposed rail line almost entirely with public funds provided on concessional terms, then hope that other coal mines in the Basin would render it profitable.

The apparent transfer of ownership of the rail project to an Adani-controlled company in the Cayman Islands supports this idea.

A third possibility, is that by making continuous new demands on governments for concessions of various kinds, Adani will eventually be able to blame government policy for the project’s failure, and on this basis extract compensation. If this is the strategy, it has so far been foiled by the abject compliance of governments at all levels.

The Adani mine-rail-port project is not commercially viable, even under the most optimistic assumptions. That Adani has failed to achieve final close reflects the dubious economics on which this project is based.

While much remains obscure, it is clear that any public funds advanced to the project – a project that does not have the consent of the Traditional Owners – will be at high risk of loss.

There is no future for exploitative developmentalism. The economy of the future will depend on sustainable management of resources, a task in which Indigenous communities must play a central role.

This follows the general (though not universal) recognition of the principle, following the Mabo decision, that Indigenous people have the right to play a role in determining the appropriate use of their land.

But this is not simply a nice ideal that will come about through sensible public policy development. This is a brutal contest for land and resources that started with colonisation.

W&J claimants fighting the State Government, Adani and their backers, are at the leading edge of this contest and the latest in the long historical land grab in Australia.

PLEASE CONSIDER SHARING THIS STORY ON SOCIAL MEDIA: New Matilda is a small independent Australian media outlet. You can support our work by subscribing for as little as $6 per month here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.