We live in difficult times, but there’s a light on the horizon if we care to look, and read, writes Dr Richard Hil.

Enter most book shops these days and you’ll see shelves groaning with post-mortems on Brexit, Trump etc. It’s a feast of agonised commentary laced with suggestions as to how we might resist the latest political calamity.

Yet events in London, Washington DC and elsewhere are evolving so rapidly and unpredictably that many of these books are soon out of date. That’s the problem with a lot of what we might call reactive-media-cycle commentary: it’s rapidly neutralized in the face of emerging events.

On the other hand, many other perhaps more considered books have appeared on the scene. Focussed on what is a rapidly changing ideological landscape these accounts have dared to peer into the future. You might think this is just another publishing fad, yet another round of intellectualising, or more likely, I would argue, it’s the sign of an imminent, swirling zeitgeist.

Lets’ trot out the titles and authors of some of these tomes: No is not enough by global activist Naomi Klein; Post Capitalism by English journalist Paul Mason; The End of protest by US activist, Micah White; Utopia for realists by Dutch Ted Talk star, Rutgers Bregman; Optimism not despair by stratospheric intellectual, Noam Chomsky; Reclaiming the State by Bill Mitchell and Thomas Fazi; Talking to my daughter about the economy by former Greek finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis; Doughnut economics: Seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist by Kate Raworth; and Out of the wreckage by the irrepressible George Monbiot.

Each author applies her/his own unique interpretation of the current state of play, although they also share a lot in common, most notably a conviction (based on the available evidence) that the neoliberal project has run its course. Actually, their conclusions are more pronounced than this: the latest phase of laissez faire capitalism, they argue, is wreaking economic and spiritual havoc on populations across the globe (notwithstanding all the Pollyanna claims); and is taking us to the very brink of environmental destruction.

Not surprisingly – and after depressing the hell out of us – the authors insist that we need to draw inspiration from an entirely different set of values and beliefs to guide us into the future.

George Monbiot is perhaps the most compelling of visionaries in this regard, spelling out the sort of principled, value-oriented narrative that can assist us in confronting the rampant individualism and competitiveness associated with free market fundamentalism.

There are references aplenty in Monbiot’s story to the failings of neoliberalism as well as to how we might set about rebuilding communities, neighbourhoods; reconnecting with nature and ourselves, developing more cooperative and sustainable economies, foregrounding peace and cooperation in policy making, and creating a new sort of inclusive, citizen-based politics in the context of a progressive nation-state.

Monbiot goes further, calling for the dismantling and reconfiguration of international institutions like the UN and the creation of a global government dedicated to human rights, social justice and the preservation of the planet. He also evokes ideas of the commons, communitarianism and localism as key elements in this narrative, and calls for the re-centring of kindness, compassion and care in deliberative policy-making processes. Monbiot’s is a story of purposeful intention, as well as a celebration of the things that make life worth living.

This is the sort of narrative it might be possible to share in a conversation in the local RSL, assuming there was a willingness to do so. It’s timely and down to earth, but also passionate, informed and persuasive. Monbiot invites us to advocate these values and principles with confidence, to spell out what an alternative world might look like, and how we can get there.

Nowadays people are more receptive to this stuff. Given the pandemic of disillusionment that has taken hold in many western countries, including Australia, there is a preparedness to entertain such narratives rather than to simply dismiss them as irrelevant or utopian.

The public mood has changed. It’s changed in large part because of a frustration with the chasm between promise and reality, and from witnessing the rampant greed of the rich and powerful. The “American dream”, the idea of the “fair go”, and the British penchant for all things decent, seem to have evaporated in the face of growing inequality, wage stagnation, underemployment, personal debt and the ravages of economic globalisation.

Shareholder capitalism has failed to deliver the promised nirvana, economic growth has faltered, and the trickledown effect has been exposed as the self-serving myth it has always been. Demonstrably, neoliberal capitalism has enriched the plutocrats who appear hell bent on what David Harvey refers to as “accumulation through dispossession”.

Certainly, the vast new class of precariat labour would attest to this reality, pointing to mass casualisation, underemployment and the erosion of pay and conditions in the new gig economy. For the well healed, this world of precariousness is regarded as the precondition for increased “productivity” facilitated by workplace “reforms”, “flexibility” and labour market “competitiveness”.

In reality however, the world of precarious labour means lower wages, increased managerial power and the further accumulation of capital for the already rich.

For many of those on the margins, the simple messages trotted out by divisive demagogues can be appealing. This romance however is likely to be short lived as the full effects of concentrated corporate power take hold. No amount of blaming other marginalized groups can draw attention away from the fact that the rich and powerful have drawn on questionable theories of human nature and introduced “economic reforms” in a bid to further enrich themselves.

The push-back against all this comes in many forms: from calls for the revitalisation of organised labour, redistributive fiscal policies, through to tougher regulation of corporations, job guarantees and the Universal Basic Income.

Some see a shift away from neoliberal capitalism through an organic, technologically driven hybridisation of commercial activity, while others call for a reclaiming of the state and an organised social movement capable of taking hold of the reins of power. None of the above writers really believe that the current system can be reformed.

This urgency for change has gained momentum over recent times because of the threat of anthropogenic climate change. For Klein and others, death wish capitalism and climate catastrophe go hand-in-hand. It’s hard to argue with this when mining corporations, assisted by lobbyists, finance companies and governments, conspire to belch out C02 at ever-higher levels, thumbing their noses at both science and public opinion.

Opposition to neoliberalism is of course far from new; it’s been building since the late 1970s. A steady flow of critical commentary has cast a long shadow over neoliberal capitalism. The only difference now is that this critique has morphed into a full-blown project of re-imagination, and it’s both challenging and absorbing: the necessary precondition for bringing about system change.

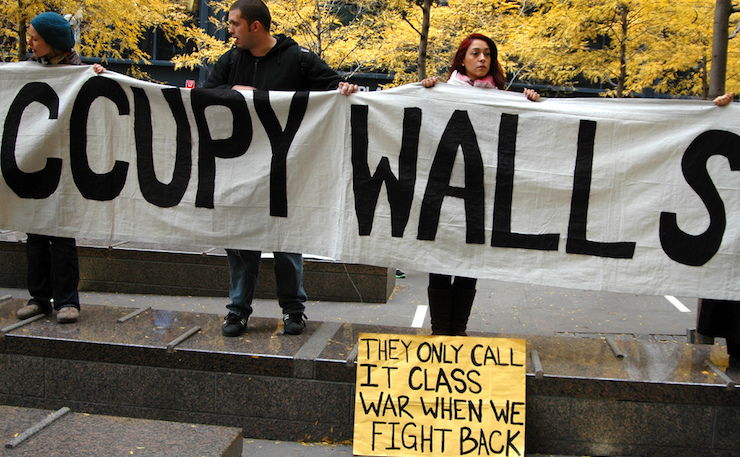

Despite various attempts to shut down this critical juggernaut, the articles and books, opposition and protests, just keep coming. They come at a time of growing interest in new paradigms and reflect a groundswell of anger and opposition to the machinations of the plutocratic elites. People are engaging in this stuff because they want change; rapid change.

But there are the usual ironies. The sales of such books are a huge revenue boon for many leading publishing houses who are far from immune to the lure of profit making. That may sound a little trite until you consider that one of the most popular documentaries on Netflix is Noam Chomsky’s Death of the American dream! It is quite possible for such brilliant work to be absorbed by the very system under attack.

Don’t get me wrong: it’s absolutely vital to the progressive cause that such work reaches a mass audience. Books by the likes of Chomsky play a vital role in helping to build activist social movements.

Still, the ability of capitalism to absorb dissent should never be underestimated. What often appears like an alternative to capitalist enterprise is soon turned into its mirror image or is corrupted to the point of no return. We’re seeing this effect in relation to some aspects of the so-called sharing economy which, rather than putting the skids under capitalism, serves to provide a new wellspring for surplus value.

Alternatives can also generate countless unintended consequences: witness the contribution made to the housing affordability crisis by the rise of Airbnb and various concerns over crypto currencies (even though blockchain technologies hold many democratic possibilities).

Consider also the dark corners of the social media empire. Claims that the internet, Facebook, Twitter and other supposedly open access platforms are giving rise to new democratic possibilities are countered by the fact they also serve to open up new market opportunities, erode privacy, increase surveillance, and enhance individuals’ sense of isolation and loneliness.

Untangling ourselves from this web is difficult. It’s how the current system endures: through coercion, illusion and co-option. It’s important to understand how we got to this point before we can truly begin the process of dismantling neoliberal capitalism.

We now have some idea of the ways in which the plutocrats created the conditions for the neoliberal takeover. It wasn’t simply imposed from above. Rather, its tentacles have stretched into every corner of society. Neoliberalism has always been more than a matter of economics; it was and remains a project aimed at changing the hearts and minds of us all. If we fail to understand this then we are bound to the same fruitless oppositional politics that characterised generations of left activists.

What is especially appealing about Monbiot’s thesis is that he sees the dismantling of the current system occurring through myriad strategies and tactics. He rightly notes that alternative practices are already rendering aspects of the current system obsolete, and that social movements have helped alter how millions of people view the world.

But none of this is easy; its sometimes painfully slow, detailed and arduous work. No-one has all the answers, there is no blueprint, and there is no end game or nirvana. Demagogues, evangelists and intellectual snobs are to be avoided at all costs. What we have before us is an evolving conversation that is vital, urgent, passionate and informed – and in many instances, truly visionary. Few now delude themselves that if we “topple” the current system then all will be well.

It seems to me that the most important thing we can do right now, as George Monbiot suggests, is to set out as clearly as we can the values upon which our principles rest, and how these can guide our deliberations into the future.

This is the backbone of the story told by George Monbiot: a story of our innate tendency toward cooperation and altruism, our deep need for connection with each other and with that space we call ‘nature’. It’s a story also of a desire for peace, security and a sense of fairness and equity.

This is not the way of the world as we currently know it. And yet; we can have it all – peace, justice and sustainability. It’s all possible. There is nothing inevitable, God-given or insurmountable in the current order of things. There is a way out of the wreckage.

PLEASE CONSIDER SHARING THIS STORY ON SOCIAL MEDIA: New Matilda is a small independent Australian media outlet. You can support our work by subscribing for as little as $6 per month here.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.