Alice Krupa worked on Manus Island in 2015-2016. She met Hamed Shamshiripour, a man who died 10 days ago after enduring four years of engineered cruelty at the hands of the Australian Government, and Papua New Guinean authorities. Here, she reveals details about life on Manus, and the daily outrages forced on detainees.

I commenced as a Broadspectrum case manager at the Manus Island Regional Processing Centre (MIRPC) in December 2015. At the time I had been a social worker for seven years, working in the Victorian mental health and out of home care systems.

Prior to Manus I had never worked for a service provider that had in place a plan to systematically break down a group of vulnerable people. I had never worked under a government department with a strategy to impede access to appropriate medical care. I had never witnessed in my workplace repeated and intentional disregard for basic human rights and international law.

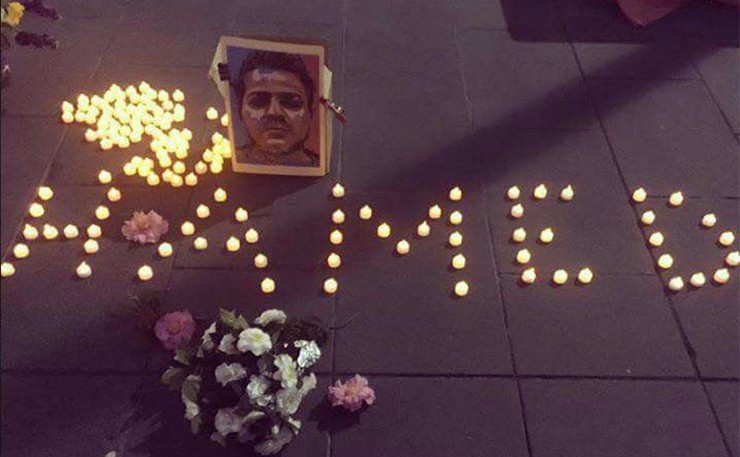

It was in this environment that a young Iranian asylum seeker, Hamed Shamshiripour, became acutely mentally unwell. It was under this strategy that he was denied appropriate treatment, leading to his death near the grounds of a Lorengau primary school.

Manus as an island is beautiful – with thick tropical rainforest surrounded by white beaches. From the airport there are two roads that lead to the MIRPC. When I first arrived at the centre I was struck by the basic nature of the facilities, in a camp that had, at that stage, been hosting the men for three years.

The refugees assured me that Broadspectrum had made many improvements to the camp since taking over from G4S. Many had experienced a long refugee journey, had been displaced in unsafe camps and were not as concerned about the standard of their accommodation, food or clothes as they were about their imprisonment.

The refugees were farmers, accountants, journalists, artists, programmers, veterans and students. They spoke multiple languages, watched the news closely, debated politics, had heated cricket and soccer tournaments, sung, composed, drew, crafted and painted with whatever materials they could access.

One of the refugees called Manus his “university”. Many focused on preparing for life after the MIRPC, trying to perfect their English, pouring over the few textbooks that they had managed to acquire.

Conversations invariably revolved around politics, religion and the future of Manus.

There was a collective experience of separation and displacement which united the men. The loss of someone’s wife, mother or child was felt throughout the camp, and there were steady streams of visitors to anyone with a recent bereavement.

On my third rotation, I was watching a soccer match when one of the players slowly dropped to the ground. A Wilson Security guard performed CPR, while the on looking refugees waved the ambulance in, unloaded the stretcher and mobilized in a desperate attempt to ensure his survival.

That evening the players sat in a line with their heads down along the fence. There was a heaviness across all of the compounds, as my colleague described, it was the feeling that no-one wanted him to die on Manus, not trapped here.

In the months following, more than 2,000 kilometres away, there were two deaths on Nauru, and a young woman, Hodan Yasin, sustained serious burns after setting herself on fire. In response, the Manus men set up memorials in the Mess areas, while the staff were given a half hour training session in how to extinguish someone who had self immolated.

In August 2016, Kamil Hussain drowned on Manus. It devastated the Pakistani community, and the subsequent initial refusal of Australia to arrange for the repatriation of his body compounded matters. Four months after Kamil died, it was Faysal Ishak Ahmed who passed away on Christmas Eve 2016 after having been unable to convince the health contractor IHMS that he was ill.

Eight months after Faysal, it was Hamed.

I did not know Hamed well. In the brief interactions we had, he was quiet and polite. We spoke about Melbourne as he had been in the MITA detention facility for medical treatment – he still wore a bandage on his knee. He would sit outside in the afternoons with peers.

Then Hamed became unwell.

By June 2016, he was behaving erratically for days on end, he was loud, had delusions of grandeur, would go from singing angrily to crying.

Initially there were protections in place for Hamed. Wilson Security staff were physically monitoring him. The health provider IHMS would come to the compound but would leave, unable to engage him in meaningful interactions. His friends were constantly trying to distract, calm and pacify him, in shifts, to the point of exhaustion.

Early on, Hamed managed to board a bus, leaving the centre and had to be coerced back by refugees and security after disturbing a church ceremony in Lorengau. Broadspectrum and Wilson Security were, at this time, very concerned with the thought of Hamed accessing the community and discussed strategies to try to prevent this from re-occurring.

However, just a few weeks later, and still experiencing acute mental ill health he was relocated from the Manus jail to the East Lorengau Regional Transit Centre (ELRTC). He had not received a Positive Refugee Status Determination – the criteria for moving to the community.

Hamed attempted to return to the MIRPC on occasion but he was physically escorted back.

After this, Hamed was reported to have been in and out of the Manus jail, experienced regular beatings and frequent periods of homelessness. Australia had washed their hands of Hamed – and this was a death sentence for a man unable to care for himself.

There is no question that Australian Border Force’s Chief Medical Officer, Dr John Brayley knew the risks. The former Manus Province MP, Ron Knight reported that he approached the Australian High Commission advocating for Hamed to be “committed to a psychiatric facility”.

“The response to me was basically that our [PNG] authorities should handle it,” Knight told the Guardian.

Even after his death the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) were still towing this line, advising The Project that questions in relation to Hamed’s death should be directed to PNG.

Although Hamed’s treatment was shocking, his lack of care was not unusual or unique, on an island that has little effective oversight. On multiple occasions the health concerns of refugees would be dismissed, with Broadspectrum team leaders advising that, off the record, IHMS believed that the men were lying, exaggerating, drug seeking or faking their symptoms. This was despite rates of depressive or anxiety disorders and PTSD among the men in MIRPC being found to be “amongst the highest recorded rates of any surveyed population”.

Physically and psychologically unwell men were left in the compounds in the care of other refugees while IHMS had empty inpatient beds. Wilson Security staff would often become frustrated watching men deteriorate in the compounds, with IHMS not acting unless they could be brought up to the clinic.

There was a man with apparent neurological deterioration, who was cared for by his peers on a daily basis. The staff acting outside of official channels to raise concerns would find that the roadblocks continued.

Within Broadspectrum, the welfare services were largely ceremonial. On-the-ground staff, and I believe our team leaders, were kept in the dark about operational changes in order to prevent leaks. I was not allowed to directly approach any of the other service providers for coordination of care – with the exception of the torture and trauma counsellors (OSSTT).

I could not accompany any of the refugees to their IHMS appointments, follow up on complaints or requests, or even approach the Broadspectrum managed Stores Department to get a refugee a pair of socks.

On one occasion, I was told to get the friends of a man who was unwell to wash his clothes and clean his room. These friends had already been providing daily care with showering and feeding. I wasn’t allowed to assist with this task – it was “not my role”. The men had no gloves and no protection, and I highlighted the contamination risk to no avail.

For all issues, the men needed to submit a request and if this failed, they could submit a complaint. Complaints were investigated internally, meaning IHMS complaints were investigated by IHMS, Broadspectrum complaints investigated by Broadspectrum, Wilson Security complaints investigated by Wilson Security.

The men would typically receive an answer finishing with a statement along the lines of “your complaint is now considered actioned and closed”.

The refugees’ complaints, including assaults and thefts, were viewed with suspicion and there was little recourse despite the number of cameras in the centre. Some men told me that they had experienced repercussions for submitting complaints from the subjects of their complaints. Another refugee lamented that, “if I hit security it happened, if he hits me it’s alleged”. When I reported a refugee’s concerns that Hamed was being beaten, I was informed that the police had been “quite patient with him considering”.

This is indicative of a level of violence that is considered normal on Manus. A 2016 -17 report from Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) found that there was missing footage from Wilson Security: “There were records of incidents which noted that video existed of an incident, but no corresponding video,” it stated. “During incidents there were gaps in the recording of incidents.”

Documentation was also an issue. On Manus, things were rarely put in writing. Information was read out at hastily convened briefings, emails were responded to verbally, and letters and complaints were returned, signed by the contractor rather than an identifiable person. The Individual Management Plans (IMP), written monthly by case managers covering health and wellbeing indicators, were not used for care planning, and issues identified in the reports were rarely followed up.

At one stage, I was asked to write a Welfare Check on a man I had not seen since arriving for my rotation and I was encouraged to just record “what I would usually write” and then check on him later. I declined, knowing that if I had done this, my Welfare Check would have been documented as fact at the joint daily stakeholder Psychological Support Program (PSP) meeting.

On other occasions, I would find my Welfare Check reports inaccurately recorded in the PSP meeting minutes. A colleague confided concerns that she had noticed that Incident Reports and case notes she had recorded had vanished.

There were no illusions about who was running things on Manus. At our arrival and departure briefings Broadspectrum Management would refer to our contract being with the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP) and that they were our client. During operational changes or major incidents, regular “atmospheric reports” were prepared by our team leaders “for Canberra” and we were asked hourly to report on the mood of the compounds.

The stakeholders on the island are under DIBP contracts – from the lawyers, psychiatrists, the cultural team and interpreters. This created a conflict of interest which prevented the men from being able to obtain the independent support they needed.

A former Playfair employee, Elizabeth Thompson outlined how the “intimidating and controlling behavior of DIBP” affected the ability of the migration lawyers on Manus to adequately provide for their clients. It added a psychological barrier to accessing services for refugees, who were aware that these services were contracted by the body responsible for their imprisonment.

I wonder how much the MIRPC has also contributed to the perceptions of corruption and disempowerment for the people of PNG. Lawyer, Loani Henao describes how PNG, under Australia’s influence had amended its constitution to the benefit of Australia.

When the PNG Supreme Court declared the centre illegal, for a brief moment, everyone thought it was the end. I remember my colleague’s face, his wide smile as he showed me the article. However, in the days and weeks after, little changed.

Arrangements were made to “open” the centre by allowing refugees to travel into Lorengau, security had less power to restrict movement and had to negotiate rather than use restraint or force. This did not stop occasions of deprivation of liberty, with the gates being locked as recently as 4th August 2017.

The ongoing operation of the detention centre since then has demonstrated a lack of respect for the rule of law of our close Pacific neighbour.

For the men on Manus, the day-to-day monotony is compounded by uncertainty. There is always something on the horizon on which the refugees can pin their hopes. And then there is the inevitable disappointment, evidenced perfectly by the Trump – Turnbull transcript leaks.

Imran Mohammad, articulates this psychological strain: “We feel like there is no place for us on this earth”.

Systematic attempts to keep the refugees in a perpetual state of fear, chaos and uncertainty creates an environment where rumours thrive. There would be announcements made by PNG ICSA (Immigration) that never eventuated, the men are not trusted to be informed about upcoming changes which prevents them from being able to plan accordingly. Even now, there are men being moved to Port Moresby under the guise of medical treatment in much larger numbers than the hospital can accommodate.

There are untruths put out by the Immigration Minister, for which there is no accountability. Despite his statements being contradicted by the Police Commander, David Yapu, the Minister insisted on painting a picture of the Good Friday shooting incident, which had the refugees portrayed as being responsible when in truth, they were the victims.

Peter Dutton has announced that there will be an inquest into the death of Hamed. If done properly, those at the top of ABF will come under intense scrutiny. However, this will be futile if it doesn’t prevent more deaths.

In recent weeks there have been increasingly frequent attacks on refugees in Lorengau. There is currently a man in a coma, flown to Australia just last week, a staggering four days after he was beaten sustaining a fractured skull.

The community of Lorengau was never supposed to be a settlement option for the men. It is a small town which is now experiencing increased strain affecting food prices, jobs and access to goods, services, medications and health care, due to the addition of extra men in their community. There are guaranteed to be continued assaults and injuries if the forced relocation to Lorengau proceeds.

For months after my resignation, I would see the faces of Manus men on the streets of Melbourne, before realizing that it could not be them, that they were still languishing in the centre. Like many people, I am hoping for a Royal Commission.

The whistleblower laws, the media bans and the secrecy is futile when everything has been documented in first-hand accounts by the refugees themselves; the journalists, artists, and note takers. Not to mention what has been witnessed by the hundreds of Papua New Guinean, Australian and New Zealander lawyers, health professionals, security officers, welfare workers, administration and humanitarian agencies who have passed through the centre.

Recently I reflected on a conversation I’d had with a Manus refugee. I had told him a story about an Australian man I had sat next to on the plane who didn’t have an understanding of Manus, and that I thought if Australian people understood what was occurring on Manus then they would put a stop to it.

He replied “Yes, but it is their responsibility to know.”

And he is right. It is our responsibility to know, and to act.

Ed’s note: Readers who want more details on the life and death of Hamed, should read this story on the Huffington Post by Iranian journalist Behrouz Boochani, who also spent four years locked up on Manus.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.