A global community indifferent to the plight of people fleeing war and famine needs to learn a new language, writes Professor Stuart Rees.

Two languages carry the means of recovering humanity and rescuing refugees. The first is expressed with words, the second in non-verbal symbolism found in music, art and dance.

Each language expresses personal fulfilment in actions concerned with beauty, love and non-violence. In writing and painting, composing and dancing, an emphasis on the interdependence of all people is a common theme.

From Poets & Philosophers

The 16th century English poet John Donne wrote, “No man is an island entire of itself; every man is a piece of the continent, a part of the main.”

In similar vein, but in the 1960’s, the Australian Aboriginal poet Kath Walker finished her poem All One Race, “I’m international, never mind place; I’m for humanity, all one race.”

In his book No Future without Forgiveness, Desmond Tutu highlighted the Zulu word ‘ubuntu’- ‘I am because you are.’ This quality, said Tutu, captures the chemistry of relationships which builds identity and expresses a crucial humanness.

In the 18th century, the philosopher Immanuel Kant crafted a universal basis for ethics which derived from the principle that human beings should never be treated as means to an end but should be regarded always as an end in themselves. If such a value held in Australia’s policy towards refugees, politicians in Canberra who wanted to appear strong, would not do so by imprisoning asylum seekers on Manus Island and Nauru.

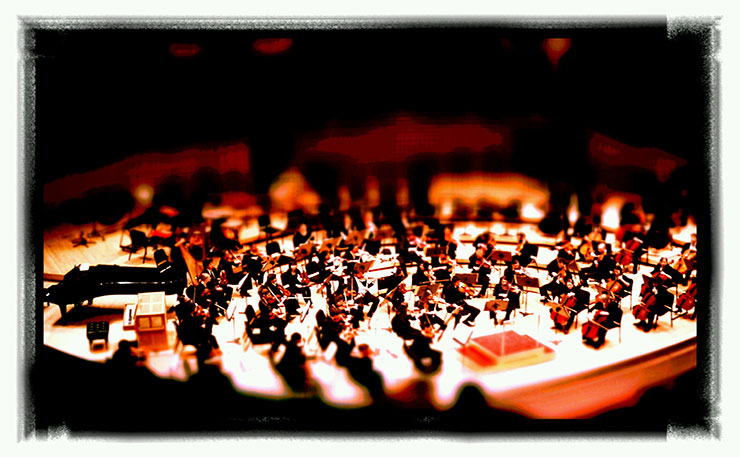

From Composers & Musicians

Musical expressions of people’s interdependence have crossed countries and cultures. In my Colorado university days, a colleague from Colombia taught a course called ‘the sociology of dance.’ She traced a history of dance to show how people across South America had danced to experience solidarity and oppose dictatorships.

Composers of symphonies have known how to use their genius to dramatize the plight of the vulnerable and to challenge oppressive regimes. In his fifth Symphony and with poetic subtlety, Dmitri Shostakovich challenged the oppression of the Stalin regime. His listeners got the message.

Through his foundation ‘pianos for peace’, and in his composition, Syrian Symphony, the Syrian concert pianist Malek Jindali remembers his country’s half a million civil war dead, including 55,000 children. Malek’s beautiful, empathic works show how music remembers the slaughtered and surviving refugees. His language also speaks opposition to the Syrian dictator Bassar al-Assad and to those who carry out his orders. “Nothing else seems to work,” says Malek.

One of the most remembered composers said he wanted his final symphony to be a victory for humanity, inside and outside the concert hall. Beethoven’s ninth symphony is often referred to as the peace symphony because the words in the last movement, sung by the chorus and by soloists, came from the German poet Schiller’s work, Ode to Joy. To express peace through an interdependence of peoples, Schiller wrote that he wanted his words to be a kiss for the whole earth.

In terms of the European Union’s insistence on the value of being generous to refugees, it’s worth remembering that the final movement of Beethoven’s ninth is the EU’s national anthem, and that the goal of achieving peace via inclusiveness was the motive for the creation of the European Union. The British people who voted for Brexit could take notice, so too the East European governments, Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic which refuse to admit asylum seekers.

Pop and folk musicians have long held visions of a world which encourages respect for a sovereignty of people as opposed to a selfish, go-it-alone patriotism. John Lennon imagined, ‘… all the people living life in peace.’ Then he requested, ‘I hope some-day you’ll join us, And the world will be as one.’

Despite such utopian visions, dark corners of cruelty persist: vindictiveness to refugees, the brutal proxy wars in Syria, indifference to the appalling punishment imposed on citizens of Gaza, let alone the cruel famine in Yemen.

Recovering Humanity

How will the public and politicians respond? Bob Dylan’s, ‘How many time must a man look up and pretend that he just doesn’t see?’, needs to be answered.

One of the most telling answers came from the French diplomat, author, activist Stephane Hessel who at the age of 91 wrote the pithy best seller, ‘Indignez Vous’ – ‘Be Outraged.’ Regarding cruelty towards refugees, in particular Palestinians, Hessel argued that those who were not outraged by such injustice had lost touch with their humanity.

Speaking the musical, poetic and artistic language of humanity can rescue refugees provided that policies flow from such language. If hearts are to be opened and values changed, the words have to be spoken, the music needs to be heard.

In Europe, the leaders of Poland, Hungary and the Czech Republic need to learn that language. So too do the indifferent ‘money rich but values poor’ Arab states of the Middle East.

Sudden dismay over pictures of children washed up on beaches after drowning in the Mediterranean will not be enough to craft a human rights response to the massive task of finding homes and safety for refugees. But Bertrand Russell, that inspiring philosopher, social activist and Nobel Laureate did have an aspirin-like prescription to raise hopes, defy bullies and envisage a world-wide common good.

He urged, “Remember humanity and forget the rest.”

* This is a shortened version of an address given in the NSW parliament on World Refugee Day last month.

Donate To New Matilda

New Matilda is a small, independent media outlet. We survive through reader contributions, and never losing a lawsuit. If you got something from this article, giving something back helps us to continue speaking truth to power. Every little bit counts.